Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

32 <strong>Presuppositions</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong><br />

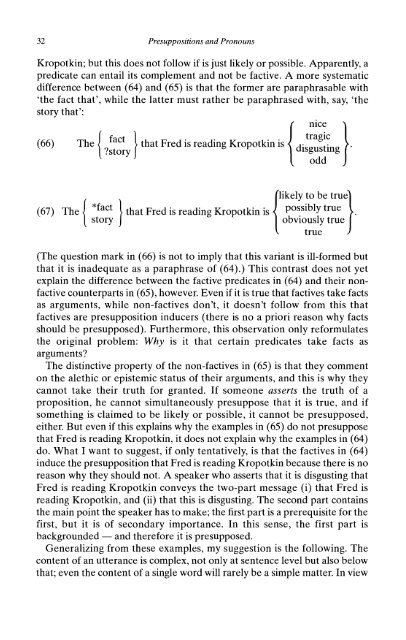

Kropotkin; but this does not follow if is just likely or possible. Apparently, a<br />

predicate can entail its complement <strong>and</strong> not be factive. A more systematic<br />

difference between (64) <strong>and</strong> (65) is that the <strong>for</strong>mer are paraphrasable with<br />

'the fact that', while the latter must rather be paraphrased with, say, 'the<br />

story that':<br />

nice }<br />

fact .. ., tragic<br />

(66) The { } that Fred IS readmg Kropotkmls disgusting .<br />

story<br />

{<br />

odd<br />

likely to be true}<br />

(67) The { *fact } that Fred is reading Kropotkin is po~sibly true .<br />

story<br />

{ ObvIOusly true<br />

true<br />

(The question mark in (66) is not to imply that this variant is ill-<strong>for</strong>med but<br />

that it is inadequate as a paraphrase of (64).) This contrast does not yet<br />

explain the difference between the factive predicates in (64) <strong>and</strong> their nonf<br />

counterparts in (65), however. Even if it is true that factives f take facts<br />

as arguments, while non-factives don't, it doesn't follow from this that<br />

factives are presupposition inducers (there is no a priori reason why facts<br />

should be presupposed). Furthermore, this observation only re<strong>for</strong>mulates<br />

nonfactive<br />

the original problem: Why is it that certain predicates take facts as<br />

arguments<br />

The distinctive property of the non-factives in (65) is that they comment<br />

on the alethic or epistemic status of their arguments, <strong>and</strong> this is why they<br />

cannot take their truth <strong>for</strong> granted. If someone asserts the truth of a<br />

proposition, he cannot simultaneously presuppose that it is true, <strong>and</strong> if<br />

something is claimed to be likely or possible, it cannot be presupposed,<br />

either. But even if this explains why the examples in (65) do not presuppose<br />

that Fred is reading Kropotkin, it does not explain why the examples in (64)<br />

do. What I want to suggest, if only tentatively, is that the factives in (64)<br />

induce the presupposition that Fred is reading Kropotkin because there is no<br />

reason why they should not. A speaker who asserts that it is disgusting that<br />

Fred is reading Kropotkin conveys the two-part message (i) that Fred is<br />

reading Kropotkin, <strong>and</strong> (ii) that this is disgusting. The second part contains<br />

the main point the speaker has to make; the first part is a prerequisite <strong>for</strong> the<br />

first, but it is of secondary importance. In this sense, the first part is<br />

backgrounded -— <strong>and</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e it is presupposed.<br />

Generalizing from these examples, my suggestion is the following. The<br />

content of an utterance is complex, not only at sentence level but also below<br />

that; even the content of a single word will rarely be a simple matter. In view