Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Presupposition 31<br />

describes a transition from one state to another: from growing tulips tUlips to not<br />

growing tulips (63a), from not growing tulips to growing tulips (63b), <strong>and</strong><br />

from growing tulips to growing even more tulips tUlips (63c). In each case it is the<br />

initial state whose existence is presupposed, not the ensuing one, <strong>and</strong> this<br />

observation turns out to apply to all transition verbs (apart from those in<br />

(63) there are: discontinue, go on, persist in, <strong>and</strong> so on) as well as to particles<br />

like still, already, anymore, <strong>and</strong> so on. Of course, this regularity could be<br />

captured by devising a rule that states that all these items have this property,<br />

instead of stipulating it <strong>for</strong> each separately,19 but one suspects that this rule<br />

should somehow follow from some semantic <strong>and</strong>/or pragmatic property that<br />

these expressions have in common.<br />

It should be noted that, intuitively speaking, it is eminently reasonable that<br />

aspectual verbs should have the presuppositions that they in fact have. It<br />

seems unlikely that we should ever come across a verb that meant exactly the<br />

same thing as begin with the only difference that it presupposes what begin<br />

asserts <strong>and</strong> vice versa. And I believe that it is intuitively clear why this should<br />

be so. It is because interlocutors are more interested in where the story is<br />

leading to than where it came from, <strong>and</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e tend to take the past as<br />

given. If a change is described, the initial state is in a sense backgrounded<br />

because we are more interested in the present <strong>and</strong> the future. And this<br />

backgrounding corresponds with presupposition.<br />

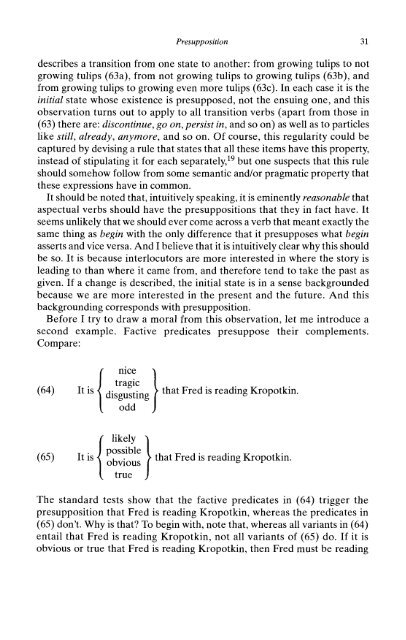

Be<strong>for</strong>e I try to draw a moral from this observation, let me introduce a<br />

second example. Factive predicates presuppose their complements.<br />

Compare:<br />

(64)<br />

nice }<br />

. tragic .. .<br />

It IS disgusting that Fred IS readmg Kropotkm.<br />

{<br />

odd<br />

(65)<br />

likely }<br />

. ossible .. .<br />

It IS Pb· that Fred IS readmg Kropotkm.<br />

{ o VIOUS<br />

true<br />

The st<strong>and</strong>ard tests show that the factive predicates in (64) trigger the<br />

presupposition that Fred is reading Kropotkin, whereas the predicates in<br />

(65) don't. Why is that To begin with, note that, whereas all variants in (64)<br />

entail that Fred is reading Kropotkin, not all variants of (65) do. If it is<br />

obvious or true that Fred is reading Kropotkin, then Fred must be reading