Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

178 <strong>Presuppositions</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong><br />

breaks into the house <strong>and</strong> takes the silver, which is not what the second<br />

sentence in (6) means. Rather, this sentence seems to say something like:'// 'If<br />

a thief broke into the house, he would take the silver.'<br />

It is a familiar observation that the meaning of a modal expression is<br />

dependent on contextual factors. This context dependence is quite evident in<br />

examples like the following:<br />

(7) Your teeth might fall out.<br />

In this example it is perfectly clear what kind of contextual in<strong>for</strong>mation the<br />

sentence requires, at least intuitively speaking: (7) means something like 'If<br />

the circumstances were to be such <strong>and</strong> such, your teeth might fall out,' <strong>and</strong><br />

unless the context fixes what 'such <strong>and</strong> such' means, the sentence will be<br />

unintelligible. Consequently, it is difficult to imagine a conversation opening<br />

with an utterance of (7). If we put together this insight with the st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

construal of modals as quantifiers over possible worlds, we cannot but<br />

conclude that the quantificational domain of a modal expression is restricted<br />

by the context in which it occurs.1<br />

1<br />

This context dependence is Roberts's starting point. She observes that the<br />

second modal in (6) tends to be read as a conditional whose antecedent<br />

makes explicit the domain of the modal would. This is in con<strong>for</strong>mity with<br />

what we said in the preceding paragraph. What Roberts adds to this picture<br />

is a mechanism that actually fills in the modal domain with material furnished<br />

by the context. She calls this mechanism 'antecedent accommodation'.2 2 To<br />

illustrate the workings of this mechanism, let (8) be the initial representation<br />

of (6).<br />

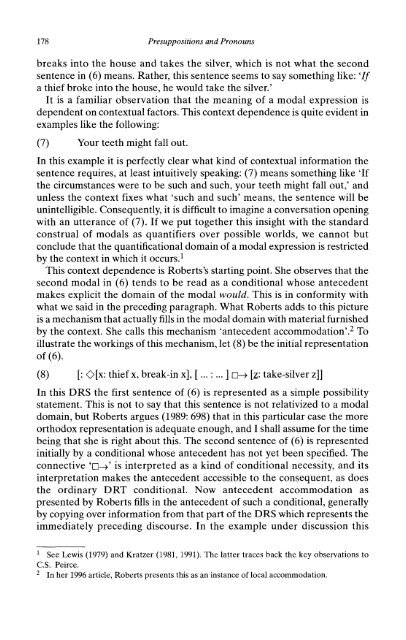

(8) [: O[x: thief x, break-in x], [...:...] ] n-> ~ [z: take-silver z]]<br />

In this DRS the first sentence of (6) is represented as a simple possibility<br />

statement. This is not to say that this sentence is not relativized to a modal<br />

domain, but Roberts argues (1989: 698) that in this particular case the more<br />

orthodox representation is adequate enough, <strong>and</strong> I shall assume <strong>for</strong> the time<br />

being that she is right about this. The second sentence of (6) is represented<br />

initially by a conditional whose antecedent has not yet been specified. The<br />

connective 'O~' 'D->' is interpreted as a kind of conditional necessity, <strong>and</strong> its<br />

interpretation makes the antecedent accessible to the consequent, as does<br />

the ordinary DRT conditional. Now antecedent accommodation as<br />

presented by Roberts fills in the antecedent of such a conditional, generally<br />

by copying over in<strong>for</strong>mation from that part of the DRS which represents the<br />

immediately preceding discourse. In the example under discussion this<br />

1<br />

1 See Lewis (1979) <strong>and</strong> Kratzer (1981, 1991). The latter traces back the key observations to<br />

C.S. Peirce.<br />

2 In her 1996 article, Roberts presents this as an instance of local accommodation.