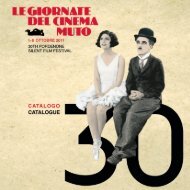

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

journal Film-Kurier on 1 January 1922: “I have always explained to<br />

Lubitsch and May that they need not care how much their films will cost.<br />

Their concern is simply to produce the best films ever. My belief is that you<br />

cannot go bankrupt because of your expenses, but only because you have<br />

not enough income. So you simply have to look for more income!”<br />

Immediately after the foundation of EFA, and following the premiere of his<br />

film Die Bergkatze (The Mountain Cat) on 12 April 1921, Lubitsch<br />

started preparations for his first EFA production (Film-Kurier, 18 May<br />

1921): “Since Pola Negri still had some commitments to fulfil, a subject<br />

had to be selected which would be principally a challenge for Emil<br />

Jannings.” Lubitsch allowed an unusually long time for production of Das<br />

Weib des Pharao. From the film’s initial conception to its premiere took<br />

seven months – a period in which the prolific Lubitsch previously would<br />

have shot at least three or four movies. His company, Ernst Lubitsch-Film,<br />

rented a 120,000-square-metre plot in the outskirts of Berlin, where fullsize<br />

sets were erected – an Egyptian village with 50 houses, several great<br />

palaces, and a high town-wall. A whole infrastructure was established to<br />

accommodate the large crowds of extras, with streets, a water supply,<br />

telephone lines, dressing rooms for 8,000 people, even a medical centre.<br />

In Emil Jannings, Paul Wegener, and Harry Liedtke, Lubitsch engaged the<br />

three most famous male film actors in Germany at that time, though he<br />

also engaged the little-known newcomer Dagny Servaes – who was given<br />

a long-term contract with EFA – to take Pola Negri’s place as the film’s<br />

female lead.<br />

The shooting was accompanied by a unique promotional campaign:<br />

journalists were transported on boats with brass bands to the location,<br />

where they were able to watch the staging of the big battle scenes<br />

between the Egyptians and Ethiopians, with thousands of extras under the<br />

command of Lubitsch. In the Berlin Zoo a big night-time procession was<br />

staged for charity, with all the actors in costume. Der Kinematograph<br />

reported in December 1921 that some 250,000 Berlin schoolchildren<br />

and their teachers were invited to visit the set after the filming was<br />

finished, to study Egyptian culture.The film was the talk of the town long<br />

before it was released.<br />

The most important innovations for Lubitsch were the new American<br />

lamps, which made possible completely new lighting effects in EFA’s<br />

“dark” studio and for the exterior night scenes. He was able to film the<br />

crowd scenes with several cameras at the same time; the battle sequence<br />

was even filmed from a balloon.<br />

The shooting was completed by the end of November 1921. Lubitsch<br />

needed nearly a whole week for the editing – normally he accomplished<br />

it personally in only three days. Following a reception on 1 December<br />

given by President Ebert, who was eager to support foreign sales of<br />

German films, on 8 December there was a private screening for the EFA<br />

staff and selected journalists, and on 10 December a farewell party. On<br />

13 December Lubitsch and Davidson sailed for America, with the first<br />

print of Das Weib des Pharao in their luggage. In New York Ben<br />

Blumenthal arranged lavish receptions and banquets to introduce Lubitsch<br />

to the American press and to promote his new film. Lubitsch proudly<br />

explained to journalists that he had worked with 112,065 extras in the<br />

29<br />

film’s production. Davidson confirmed this with bills from the costume<br />

suppliers – though obviously the extras were counted according to the<br />

days of their engagement. In his eagerness to study American films,<br />

Lubitsch attended premieres of new films by Stroheim, Griffith, and<br />

Chaplin, which greatly impressed him.<br />

Lubitsch had already returned to Germany before the film’s spectacular<br />

premiere at the Criterion Theatre, New York, on 21 February 1922. The<br />

film was “edited and titled by Rudolph Bartlett” – which involved cutting<br />

the film by about 700 metres. Among the scenes that were excised was<br />

the stoning of Ramphis and Theonis at the end of the film, to give the<br />

American version the necessary happy ending.The film’s American release<br />

title was The Loves of Pharaoh, which The Exhibitor’s Herald rightly<br />

called “a misnomer”. Otherwise, the film was highly praised: “It is one of<br />

the truly exceptional works of the screen,” said The New York Times (22<br />

February 1921). Only the acting was criticized (The Exhibitor’s Herald,<br />

11 March 1921):“The work of the individual actors fails to stand out as<br />

expected from stars of such magnitude and at times some of the parts<br />

are woefully overacted.”The film ran for 300 screenings at the Criterion,<br />

but was less successful in other towns.<br />

The German premiere on 14 March 1922 at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo was<br />

a major social event:“Even in the best times of Reinhardt no premiere was<br />

ever as crowded as Das Weib des Pharao,” wrote Kurt Pinthus (Das<br />

Tage-Buch, 18 March 1922).The screenings were sold out for six weeks,<br />

and trade papers reported that there was spontaneous applause during<br />

the battle scenes and at the end of each reel.The orchestral score, by the<br />

popular operetta composer Eduard Künneke (1885-1953), was<br />

independently reviewed in the press – the first time that a film score was<br />

taken seriously by German critics. Though the film was praised as a<br />

technical masterpiece, there were some objections (Berliner Zeitung, 20<br />

March 1922):“German spirit, German handicraft, German art – maybe a<br />

little bit too much American style, and therefore we cannot praise it with<br />

the same enthusiasm as other works by Lubitsch.” Weak points in the<br />

storyline were subsequently pointed out (Film-Kurier, 18 December<br />

1922):“From reel to reel there is a different main character – and in the<br />

end the audience doesn’t sympathize with anybody.”<br />

All in all, Das Weib des Pharao was not the most successful film of all<br />

time, as it had been anticipated to be. It failed to eclipse Madame<br />

Dubarry, and it could not save EFA, which was facing severe financial<br />

problems thanks to its arrogant behaviour, massive investments, and costly<br />

contracts.A year and a half after its foundation EFA was liquidated. Zukor<br />

lost about $2 million in this miscalculated investment.The only assets of<br />

EFA were Pola Negri, who was brought over to Hollywood in September<br />

1922, and Ernst Lubitsch, who would follow in December 1922.<br />

Today all six productions of EFA are lost, or survive only in fragments. For<br />

decades Das Weib des Pharao was available only in a print at<br />

Filmmuseum München, struck from a duplicate negative with Russian<br />

intertitles held by Gosfilmofond, and with German intertitles added and<br />

compiled from the original screenplay. Its length was about half that of<br />

the premiere version. For this new reconstruction, a project of Adoram<br />

München, Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, and Filmmuseum München, in<br />

EVENTI SPECIALI<br />

SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS