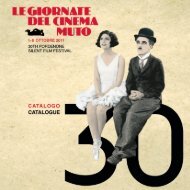

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2005 Sommario / Contents

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

his cast apparently experienced the wartime attacks on London as<br />

preparations for their performances in Hearts.<br />

Despite the prologue’s emphasis on location shooting in France, Griffith<br />

seems to have spent only two more weeks in France, during the autumn,<br />

and the only cast member who joined him there was Lillian Gish.They shot<br />

footage around the village of Ham, on the Somme, which Richard Schickel<br />

considers to be the only French location identifiable in the film. In October<br />

the group returned to the United States, and by November the cast<br />

assembled in California for the principal filming in sets. During the leadup<br />

to the filming, Griffith acquired some documentary footage of the<br />

fighting, which he spliced into his battle scenes. December saw a return<br />

to a frantic shooting schedule that probably recalled to many the days of<br />

the Biographs. Griffith began editing in January of 1918. Hearts<br />

premiered in April and went on to make a $600,000 profit – a success<br />

cut short in part by the Armistice and in part by the great flu epidemic of<br />

1918-1919 (on the film’s production and release, see Richard Schickel,<br />

D.W. Griffith, pp. 340–360).<br />

Schickel has commented on how unrealistic Griffith’s war scenes are:<br />

action, movement, and “sweeping movement” – not the grueling, static<br />

trench warfare that most of the fighting actually involved. He comments<br />

that the Boy’s two days in a shell hole come closest to that reality. In that<br />

scene, however, one has to ask what the Boy could learn after two days<br />

there that would allow him to know when to signal for the attack to begin.<br />

That one exception aside, however, Griffith’s lack of realism in depicting<br />

the war goes against his attempt to achieve authenticity by including<br />

scenes shot in France. Despite the usually seamless combination of<br />

English, French, and American-shot footage, Hearts remains as<br />

conventional in its depiction of war as the other WWI films made entirely<br />

in Hollywood.<br />

I have suggested that Griffith moved from the experimentation of his two<br />

great mid-1910s features to a sudden conservatism of film style.This was<br />

paralleled by an old-fashioned approach to story. Schickel also remarks on<br />

how clichéd and implausible the non-military scenes of Hearts are, with<br />

Griffith trapped in stage melodrama, repeating the simplified and familiar<br />

notion of threatened rape standing in for the general horrors of war. Of<br />

course The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance had many melodramatic<br />

and outdated scenes, but they seem to fade into the background in the<br />

face of daring techniques. In Hearts of the World, the most impressive<br />

moments are usually those quiet scenes that recall the best of Griffith’s<br />

Biographs.<br />

And the strengths of Hearts are definitely in its individual scenes, for the<br />

mechanics of the plot progression are clunky. The opening exposition<br />

introduces the characters at great length without setting up the sorts of<br />

goals and expectations that were becoming part of current Hollywood<br />

plotting. One need only look at the Douglas Fairbanks films being directed<br />

at this time by John Emerson and Allan Dwan to realize how lively the<br />

introduction of salient story information early in a film could be. Even in<br />

comparison with Griffith’s own exposition at the beginning of Birth, that<br />

of Hearts seems careless.There are almost no dialogue titles – something<br />

that continues to be characteristic of Griffith films well into the 1920s, at<br />

89<br />

a time when a preponderance of dialogue titles was rapidly replacing<br />

expository titles as the Hollywood norm.<br />

Hearts is also plagued by Griffith’s predilection for very short scenes,<br />

often only a shot or two.The first reasonably skillful sustained Griffithian<br />

sequence comes after the title THE LITTLEST ONE OF THE BOY’S THREE<br />

BROTHERS IS INCLINED TO HERO-WORSHIP.This leads directly into the<br />

first major love scene, introduced by another title, AFTERNOON. SHE<br />

READS HIS VERSE OF LOVE – DEATHLESS, UNENDING. Here the Boy<br />

observes her as she toys with a rose and reads his poetry.Throughout this<br />

action, however, there is no real conflict introduced.The Boy is attracted to<br />

the Girl, she loves him, and there seems to be no misunderstanding or<br />

other barrier to their romance. Even the introduction of The Little<br />

Disturber (i.e., the Singer played by Dorothy Gish) simply allows her to<br />

show off something of her character and to meet Monsieur Cuckoo, her<br />

befuddled suitor.<br />

An astonishingly long way into the film, the scene in which the Singer<br />

encounters the Boy in the street introduces some dramatic conflict.<br />

Significantly, this is also the first scene to begin without an expository<br />

intertitle.We are at last left without guidance to observe for ourselves the<br />

characters’ actions and infer their motives.The scene itself is staged partly<br />

in depth along a sidewalk by a long stone wall and specifically in front of<br />

the door to the Boy’s home. The scene contains the film’s first real<br />

shot/reverse-shot conversation and creates a lively dramatic interest for<br />

the first time as the Singer’s flirtation with the Boy develops.There is even<br />

a parallel created to the earlier scene of the Boy observing the Girl in the<br />

garden. There he had ogled her ankle, and he does the same with the<br />

Singer here – though in a more shy and confused manner.<br />

Even after this scene, however, the plodding exposition resumes, with the<br />

introduction of Von Strohm, the villainous German spy, and his relationship<br />

to the treacherous woman who runs the local village inn. Interestingly,<br />

however, the lengthy exposition ends with a scene between Von Strohm<br />

and the Girl that parallels the flirtation between the Boy and the Singer.<br />

Again the scene takes place on a sidewalk along a lengthy wall, centering<br />

around a doorway. Von Strohm notices the Girl, and as with the Boy’s<br />

interest in both the Girl and the Singer, his attraction to her is conveyed<br />

by his glance at her ankle. Just as the Singer presents a comic threat to<br />

the Boy’s romance with the Girl,Von Strohm now creates a more serious<br />

threat to that romance. A really striking touch comes at the end of this<br />

scene, as the Girl shuts the door in the German’s face, but he places his<br />

buttonhole carnation in a knothole and pushes it through toward her with<br />

the tip of his cane. This recalls the Girl’s rose in the love scene in the<br />

garden, but at the same time it is a bizarre, enigmatic gesture, perhaps<br />

suggesting defiance, perhaps seduction. A quick fade emphasizes this<br />

uncertainty.<br />

With this gesture we can say that the film’s lengthy exposition ends.The<br />

first truly sustained and well-handled scene occurs next, beginning with<br />

the title PERSEVERANCE AND PERFUME.The Singer and the Boy meet<br />

again in the street outside his door. As she flirts with him again and tries<br />

to provoke him to kiss her, a single cutaway signals that the Girl is nearby,<br />

shopping.A medium-long shot along the wall places the Singer and Boy in<br />

GRIFFITH