- Page 1 and 2:

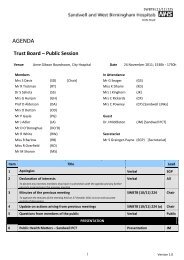

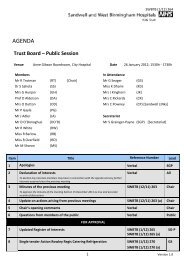

SWBTB (2/10) 026 AGENDA Trust Board

- Page 3 and 4:

SWBTB (2/10) 026 18 Any other busin

- Page 5 and 6:

MINUTES approved as true and accura

- Page 7 and 8:

MINUTES expectation that there woul

- Page 9 and 10:

MINUTES however the structure would

- Page 11 and 12:

MINUTES which was reported to be un

- Page 13 and 14:

MINUTES Mr Cash asked which communi

- Page 15 and 16:

MINUTES Mr Seager presented an upda

- Page 17 and 18:

SWBTB (2/10) 025 (a) Next Meeting:

- Page 19 and 20:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 21 and 22:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 PREVIOUS CONSIDERA

- Page 23 and 24:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Contents Page

- Page 25 and 26:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) 2. Methodology

- Page 27 and 28:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) 2.3 Reach 780

- Page 29 and 30:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) 7

- Page 31 and 32:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) 3. Option Pref

- Page 33 and 34:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Table 3 Comple

- Page 35 and 36:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) • A number o

- Page 37 and 38:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) • Satisfied

- Page 39 and 40:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) • Bad experi

- Page 41 and 42:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Table 5 Focus

- Page 43 and 44:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Some women kne

- Page 45 and 46:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) • Reputation

- Page 47 and 48:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Young people p

- Page 49 and 50:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Table 7 Showin

- Page 51 and 52:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) home birth wou

- Page 53 and 54:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Black Caribbea

- Page 55 and 56:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) White and Blac

- Page 57 and 58:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) • Labour Par

- Page 59 and 60:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Role Number of

- Page 61 and 62:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Appendix 1 Foc

- Page 63 and 64:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Appendix 2 Pro

- Page 65 and 66:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Postcode Area

- Page 67 and 68:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Chart 2: Women

- Page 69 and 70:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Chart 6: Women

- Page 71 and 72:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Chart 10: Wome

- Page 73 and 74:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Appendix 5 Com

- Page 75 and 76:

SWBTB (2/10) 035 (a) Appendix 7 Bir

- Page 77 and 78:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 79 and 80:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 IMPACT ASSESSMENT

- Page 81 and 82:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) MATERNITY SERV

- Page 83 and 84:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) All consultant

- Page 85 and 86:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) • APPROVE th

- Page 87 and 88:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) strategy the S

- Page 89 and 90:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) These efforts

- Page 91 and 92:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) risk women in

- Page 93 and 94:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) • Shorter la

- Page 95 and 96:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) Benefit Descri

- Page 97 and 98:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) From the compl

- Page 99 and 100:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) Concerns about

- Page 101 and 102:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) Stages 5 - 9:

- Page 103 and 104:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) The scheme dur

- Page 105 and 106:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) • The stand

- Page 107 and 108:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) 10. INVESTMENT

- Page 109 and 110:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) 11.2 Activity

- Page 111 and 112:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) 13. CASHFLOW P

- Page 113 and 114:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) 15. JOINT HEAL

- Page 115 and 116:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) Sandwell PCT w

- Page 117 and 118:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (a) APPENDIX 7 DOC

- Page 119 and 120:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (b) Outpatients Fi

- Page 121 and 122:

SWBTB (2/10) 045 (b) Sandwell & Wes

- Page 123 and 124:

Sandwell & West Birmingham Hospital

- Page 125 and 126:

Risk Register APPENDIX 7 Version 1

- Page 127 and 128:

Risk Register APPENDIX 7 Version 1

- Page 129 and 130:

Risk Register Impact Narrative Poss

- Page 131 and 132:

SWBTB (2/10) 036 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 133 and 134:

POLICY PROFILE 2 SWBTB (2/10) 036 (

- Page 135 and 136: Contents page SWBTB (2/10) 036 (a)

- Page 137 and 138: Infection Control Surveillance Nurs

- Page 139 and 140: 5.4.5 Infection Control Surveillanc

- Page 141 and 142: SWBTB (2/10) 036 (a) i) To circulat

- Page 143 and 144: SWBTB (2/10) 036 (a) 6.3.2. Lines o

- Page 145 and 146: 12.0 Monitoring Effectiveness SWBTB

- Page 147 and 148: SWBTB (2/10) 036 (b) Step 2 - Gathe

- Page 149 and 150: SWBTB (2/10) 036 (c) Appendix 5 POL

- Page 151 and 152: SWBTB (2/10) 036 (c) Identify which

- Page 153 and 154: SWBTB (2/10) 037 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 155 and 156: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) 1 Introduction

- Page 157 and 158: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) including the

- Page 159 and 160: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) • Has the ab

- Page 161 and 162: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) either through

- Page 163 and 164: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) If a proposed

- Page 165 and 166: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) The provision

- Page 167 and 168: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) Staff who are

- Page 169 and 170: • Does this decision need to be m

- Page 171 and 172: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) and hence impr

- Page 173 and 174: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) The consultant

- Page 175 and 176: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) Staff undertak

- Page 177 and 178: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (a) • Procedures

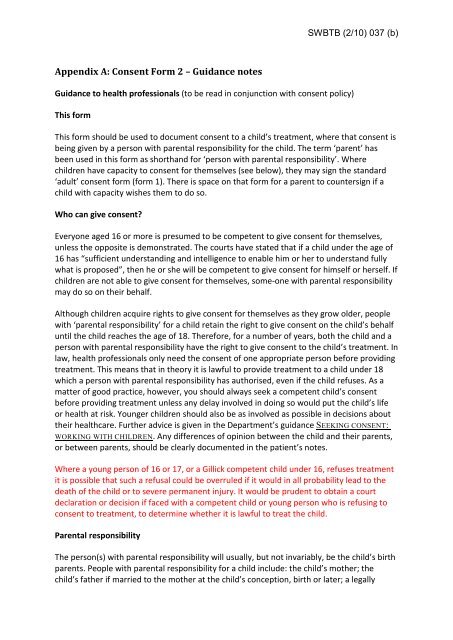

- Page 179 and 180: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) 1 Appendix A 1

- Page 181 and 182: Appendix A: Consent Form 1 - Right

- Page 183 and 184: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) You should alw

- Page 185: Appendix A: Consent Form 2 - Right

- Page 189 and 190: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Form 3 guidanc

- Page 191 and 192: Appendix A: Consent Form 4 - Left h

- Page 193 and 194: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix A: Co

- Page 195 and 196: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Second opinion

- Page 197 and 198: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix C San

- Page 199 and 200: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) The young pers

- Page 201 and 202: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix D Fun

- Page 203 and 204: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix E How

- Page 205 and 206: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix G THE

- Page 207 and 208: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (b) Appendix G3 Tr

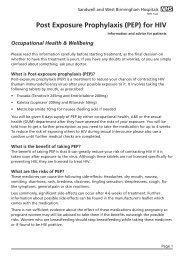

- Page 209 and 210: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) Sandwell and W

- Page 211 and 212: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) Introduction T

- Page 213 and 214: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) What are the m

- Page 215 and 216: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) How do I begin

- Page 217 and 218: Frequently asked Questions SWBTB (2

- Page 219 and 220: SAPG OCT 09 - 11 - SWBTB (2/10) 037

- Page 221 and 222: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) Q5) Who was in

- Page 223 and 224: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) Appendix B San

- Page 225 and 226: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) 4d The EIA rev

- Page 227 and 228: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (d) Date: Contact

- Page 230 and 231: SWBTB (2/10) 037 (e) KEY TASKS ISSU

- Page 232 and 233: KEY TASKS ISSUES IDENTIFIED ACTION

- Page 234 and 235: SWBTB (2/10) 029 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 236 and 237:

SWBTB (2/10) 038 ALIGNMENT TO TRUST

- Page 238 and 239:

SWBTB (2/10) 038 (a) From 2010/11 M

- Page 240 and 241:

SWBTB (2/10) 038 (a) Median rate 2.

- Page 242 and 243:

SWBTB (2/10) 038 (a) Audit and Trai

- Page 244 and 245:

SWBTB (2/10) 046 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 246 and 247:

SWBTB (2/10) 046 (a) Compliance Cri

- Page 248 and 249:

3 Provide suitable and sufficient i

- Page 250 and 251:

8 Have and adhere to appropriate po

- Page 252 and 253:

SWBTB (2/10) 027 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 254 and 255:

SWBTB (2/10) 027 (a) PEAT Expendit

- Page 256 and 257:

SWBTB (2/10) 027 (a) A study was co

- Page 258 and 259:

SWBTB (2/10) 039 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 260 and 261:

SWBTB (2/10) 039 (a) Theme Triggers

- Page 262 and 263:

SWBTB (2/10) 029 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 264 and 265:

SWBTB (2/10) 029 (a) INTRODUCTION S

- Page 266 and 267:

In terms of affordability the follo

- Page 268 and 269:

SMOCS Sandwell PEC HoBt PEC Childre

- Page 270 and 271:

As reported last month, the date fo

- Page 272 and 273:

Les Williams Programme Director 201

- Page 274 and 275:

Respiratory The Project Lead post h

- Page 276 and 277:

SWBTB (2/10) 029 (b) Sandwell and t

- Page 278 and 279:

SWBTB (2/10) 028 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 280 and 281:

With the revised activity / afforda

- Page 282 and 283:

SWBTB (2/10) 041 ALIGNMENT TO OBJEC

- Page 284 and 285:

SWBTB (2/10) 041 (a) • Release 4

- Page 286 and 287:

SWBTB (2/10) 041 (a) • Rotawatch

- Page 288 and 289:

SWBTB (2/10) 030 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 290 and 291:

SWBGB NEW REF SWBTB (2/10) 030 (a)

- Page 292 and 293:

SWBGB NEW REF SWBTB (2/10) 030 (a)

- Page 294 and 295:

SWBGB NEW REF SWBTB (2/10) 030 (a)

- Page 296 and 297:

SWBGB NEW REF SWBTB (2/10) 030 (a)

- Page 298 and 299:

SWBGB NEW REF SWBTB (2/10) 030 (a)

- Page 300 and 301:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 302 and 303:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 (a) Financial Perf

- Page 304 and 305:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 (a) Financial Perf

- Page 306 and 307:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 (a) Financial Perf

- Page 308 and 309:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 (a) Financial Perf

- Page 310 and 311:

SWBTB (2/10) 031 (a) Financial Perf

- Page 312 and 313:

SWBTB (2/10) 044 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 314 and 315:

SANDWELL AND WEST BIRMINGHAM HOSPIT

- Page 316 and 317:

Exec Lead RK R0 Readmission Rates I

- Page 318 and 319:

Exec Lead RK RK YTD 09/10 No. 6388

- Page 320 and 321:

SWBTB (2/10) 042 TRUST BOARD DOCUME

- Page 322 and 323:

SWBTB (2/10) 042 (a) SANDWELL AND W

- Page 324 and 325:

SWBTB (2/10) 043 DOCUMENT TITLE: SP

- Page 326 and 327:

SWBTB (2/10) 043 (a) DEVELOPING THE

- Page 328 and 329:

SWBTB (2/10) 043 (a) • Merge the

- Page 330 and 331:

SWBFC (1/10) 010 Finance and Perfor

- Page 332 and 333:

SWBFC (1/10) 010 this be adopted as

- Page 334 and 335:

SWBFC (1/10) 010 The Committee was

- Page 336:

SWBFC (1/10) 010 8.2 Actions and de