DEVELOPMENTAL CRISIS IN EARLY ADULTHOOD: A ...

DEVELOPMENTAL CRISIS IN EARLY ADULTHOOD: A ...

DEVELOPMENTAL CRISIS IN EARLY ADULTHOOD: A ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

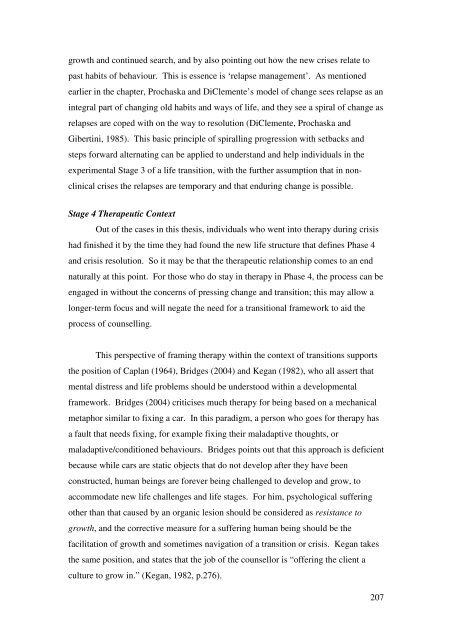

growth and continued search, and by also pointing out how the new crises relate to<br />

past habits of behaviour. This is essence is ‘relapse management’. As mentioned<br />

earlier in the chapter, Prochaska and DiClemente’s model of change sees relapse as an<br />

integral part of changing old habits and ways of life, and they see a spiral of change as<br />

relapses are coped with on the way to resolution (DiClemente, Prochaska and<br />

Gibertini, 1985). This basic principle of spiralling progression with setbacks and<br />

steps forward alternating can be applied to understand and help individuals in the<br />

experimental Stage 3 of a life transition, with the further assumption that in nonclinical<br />

crises the relapses are temporary and that enduring change is possible.<br />

Stage 4 Therapeutic Context<br />

Out of the cases in this thesis, individuals who went into therapy during crisis<br />

had finished it by the time they had found the new life structure that defines Phase 4<br />

and crisis resolution. So it may be that the therapeutic relationship comes to an end<br />

naturally at this point. For those who do stay in therapy in Phase 4, the process can be<br />

engaged in without the concerns of pressing change and transition; this may allow a<br />

longer-term focus and will negate the need for a transitional framework to aid the<br />

process of counselling.<br />

This perspective of framing therapy within the context of transitions supports<br />

the position of Caplan (1964), Bridges (2004) and Kegan (1982), who all assert that<br />

mental distress and life problems should be understood within a developmental<br />

framework. Bridges (2004) criticises much therapy for being based on a mechanical<br />

metaphor similar to fixing a car. In this paradigm, a person who goes for therapy has<br />

a fault that needs fixing, for example fixing their maladaptive thoughts, or<br />

maladaptive/conditioned behaviours. Bridges points out that this approach is deficient<br />

because while cars are static objects that do not develop after they have been<br />

constructed, human beings are forever being challenged to develop and grow, to<br />

accommodate new life challenges and life stages. For him, psychological suffering<br />

other than that caused by an organic lesion should be considered as resistance to<br />

growth, and the corrective measure for a suffering human being should be the<br />

facilitation of growth and sometimes navigation of a transition or crisis. Kegan takes<br />

the same position, and states that the job of the counsellor is “offering the client a<br />

culture to grow in.” (Kegan, 1982, p.276).<br />

207