Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

� CHAPTER 2.2.1 �<br />

PREHISTORIC QUARRYING<br />

AND THE “RE-SANCTIFICATION” OF ROCK ART<br />

* INTRODUCTION *<br />

Unfortunately, the demolition <strong>of</strong> prehistoric petroglyphs is not rare.<br />

All over Europe we find instances <strong>of</strong> the destruction <strong>of</strong> rock art due to<br />

all sorts <strong>of</strong> activities, such as <strong>van</strong>dalism, agricultural improvement or<br />

road making. One <strong>of</strong> the biggest threats however, is that <strong>of</strong> rock<br />

quarrying. <strong>The</strong> reason for this is quite clear. Conspicuous rock outcrops<br />

suitable for the execution <strong>of</strong> petroglyphs also attracted people who<br />

were looking for convenient stone quarries. This unfortunately means<br />

that especially decorated rock surfaces are prone to be destroyed by<br />

quarrying activities, <strong>of</strong>ten without at all having been recorded by an<br />

archaeological survey.<br />

Although probably hundreds <strong>of</strong> decorated rocks will thus have been<br />

destroyed, many decorated rocks fortunately have survived after all,<br />

whether because <strong>of</strong> premeditated actions or accidentally. Consequently,<br />

stones bearing prehistoric decoration are found in the strangest places<br />

such as field walls, farm buildings, museums, but also in more ancient<br />

structures such as souterrains (underground chamber-like structures)<br />

<strong>and</strong> crannogs (artificial isl<strong>and</strong>s in lakes) from the Scottish Iron Age.<br />

Unfortunately their provenance is <strong>of</strong>ten unknown in most instances.<br />

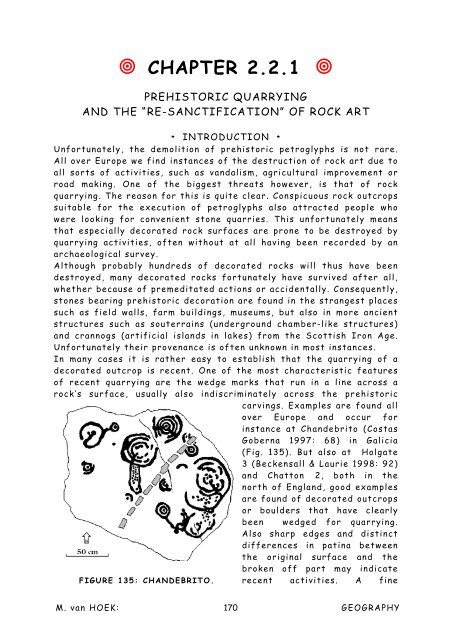

In many cases it is rather easy to establish that the quarrying <strong>of</strong> a<br />

decorated outcrop is recent. One <strong>of</strong> the most characteristic features<br />

<strong>of</strong> recent quarrying are the wedge marks that run in a line across a<br />

rock’s surface, usually also indiscriminately across the prehistoric<br />

carvings. Examples are found all<br />

over Europe <strong>and</strong> occur for<br />

instance at Ch<strong>and</strong>ebrito (Costas<br />

Goberna 1997: 68) in Galicia<br />

(Fig. 135). But also at Holgate<br />

3 (Beckensall & Laurie 1998: 92)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Chatton 2, both in the<br />

north <strong>of</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>, good examples<br />

are found <strong>of</strong> decorated outcrops<br />

or boulders that have clearly<br />

been wedged for quarrying.<br />

Also sharp edges <strong>and</strong> distinct<br />

differences in patina between<br />

the original surface <strong>and</strong> the<br />

broken <strong>of</strong>f part may indicate<br />

FIGURE 135: CHANDEBRITO. recent activities. A fine<br />

M. <strong>van</strong> HOEK: 170<br />

GEOGRAPHY