Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

Maarten van Hoek The Geography of Cup-and-Ring ... - StoneWatch

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Yet, most <strong>of</strong> these shaped<br />

stones, whether decorated or<br />

not, will have been quarried<br />

once. <strong>The</strong>refore it should be<br />

possible to trace instances <strong>of</strong><br />

the prehistoric quarrying <strong>of</strong><br />

decorated outcrops,<br />

especially in areas where<br />

petroglyphs <strong>and</strong> megalithic<br />

monuments occur together.<br />

However, for several reasons<br />

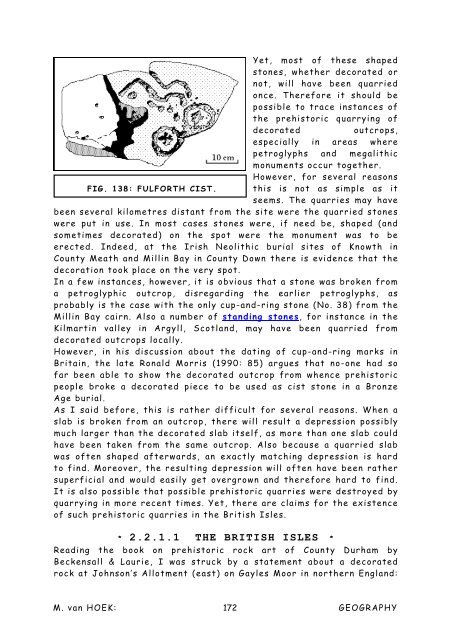

FIG. 138: FULFORTH CIST. this is not as simple as it<br />

seems. <strong>The</strong> quarries may have<br />

been several kilometres distant from the site were the quarried stones<br />

were put in use. In most cases stones were, if need be, shaped (<strong>and</strong><br />

sometimes decorated) on the spot were the monument was to be<br />

erected. Indeed, at the Irish Neolithic burial sites <strong>of</strong> Knowth in<br />

County Meath <strong>and</strong> Millin Bay in County Down there is evidence that the<br />

decoration took place on the very spot.<br />

In a few instances, however, it is obvious that a stone was broken from<br />

a petroglyphic outcrop, disregarding the earlier petroglyphs, as<br />

probably is the case with the only cup-<strong>and</strong>-ring stone (No. 38) from the<br />

Millin Bay cairn. Also a number <strong>of</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ing stones, for instance in the<br />

Kilmartin valley in Argyll, Scotl<strong>and</strong>, may have been quarried from<br />

decorated outcrops locally.<br />

However, in his discussion about the dating <strong>of</strong> cup-<strong>and</strong>-ring marks in<br />

Britain, the late Ronald Morris (1990: 85) argues that no-one had so<br />

far been able to show the decorated outcrop from whence prehistoric<br />

people broke a decorated piece to be used as cist stone in a Bronze<br />

Age burial.<br />

As I said before, this is rather difficult for several reasons. When a<br />

slab is broken from an outcrop, there will result a depression possibly<br />

much larger than the decorated slab itself, as more than one slab could<br />

have been taken from the same outcrop. Also because a quarried slab<br />

was <strong>of</strong>ten shaped afterwards, an exactly matching depression is hard<br />

to find. Moreover, the resulting depression will <strong>of</strong>ten have been rather<br />

superficial <strong>and</strong> would easily get overgrown <strong>and</strong> therefore hard to find.<br />

It is also possible that possible prehistoric quarries were destroyed by<br />

quarrying in more recent times. Yet, there are claims for the existence<br />

<strong>of</strong> such prehistoric quarries in the British Isles.<br />

* 2.2.1.1 THE BRITISH ISLES *<br />

Reading the book on prehistoric rock art <strong>of</strong> County Durham by<br />

Beckensall & Laurie, I was struck by a statement about a decorated<br />

rock at Johnson’s Allotment (east) on Gayles Moor in northern Engl<strong>and</strong>:<br />

M. <strong>van</strong> HOEK: 172<br />

GEOGRAPHY