Theism and Explanation - Appeared-to-Blogly

Theism and Explanation - Appeared-to-Blogly

Theism and Explanation - Appeared-to-Blogly

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

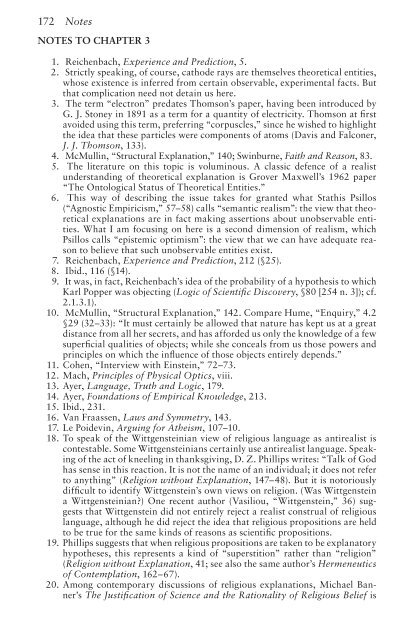

172 Notes<br />

NOTES TO CHAPTER 3<br />

1. Reichenbach, Experience <strong>and</strong> Prediction, 5.<br />

2. Strictly speaking, of course, cathode rays are themselves theoretical entities,<br />

whose existence is inferred from certain observable, experimental facts. But<br />

that complication need not detain us here.<br />

3. The term “electron” predates Thomson’s paper, having been introduced by<br />

G. J. S<strong>to</strong>ney in 1891 as a term for a quantity of electricity. Thomson at fi rst<br />

avoided using this term, preferring “corpuscles,” since he wished <strong>to</strong> highlight<br />

the idea that these particles were components of a<strong>to</strong>ms (Davis <strong>and</strong> Falconer,<br />

J. J. Thomson, 133).<br />

4. McMullin, “Structural <strong>Explanation</strong>,” 140; Swinburne, Faith <strong>and</strong> Reason, 83.<br />

5. The literature on this <strong>to</strong>pic is voluminous. A classic defence of a realist<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of theoretical explanation is Grover Maxwell’s 1962 paper<br />

“The On<strong>to</strong>logical Status of Theoretical Entities.”<br />

6. This way of describing the issue takes for granted what Stathis Psillos<br />

(“Agnostic Empiricism,” 57–58) calls “semantic realism”: the view that theoretical<br />

explanations are in fact making assertions about unobservable entities.<br />

What I am focusing on here is a second dimension of realism, which<br />

Psillos calls “epistemic optimism”: the view that we can have adequate reason<br />

<strong>to</strong> believe that such unobservable entities exist.<br />

7. Reichenbach, Experience <strong>and</strong> Prediction, 212 (§25).<br />

8. Ibid., 116 (§14).<br />

9. It was, in fact, Reichenbach’s idea of the probability of a hypothesis <strong>to</strong> which<br />

Karl Popper was objecting (Logic of Scientifi c Discovery, §80 [254 n. 3]); cf.<br />

2.1.3.1).<br />

10. McMullin, “Structural <strong>Explanation</strong>,” 142. Compare Hume, “Enquiry,” 4.2<br />

§29 (32–33): “It must certainly be allowed that nature has kept us at a great<br />

distance from all her secrets, <strong>and</strong> has afforded us only the knowledge of a few<br />

superfi cial qualities of objects; while she conceals from us those powers <strong>and</strong><br />

principles on which the infl uence of those objects entirely depends.”<br />

11. Cohen, “Interview with Einstein,” 72–73.<br />

12. Mach, Principles of Physical Optics, viii.<br />

13. Ayer, Language, Truth <strong>and</strong> Logic, 179.<br />

14. Ayer, Foundations of Empirical Knowledge, 213.<br />

15. Ibid., 231.<br />

16. Van Fraassen, Laws <strong>and</strong> Symmetry, 143.<br />

17. Le Poidevin, Arguing for Atheism, 107–10.<br />

18. To speak of the Wittgensteinian view of religious language as antirealist is<br />

contestable. Some Wittgensteinians certainly use antirealist language. Speaking<br />

of the act of kneeling in thanksgiving, D. Z. Phillips writes: “Talk of God<br />

has sense in this reaction. It is not the name of an individual; it does not refer<br />

<strong>to</strong> anything” (Religion without <strong>Explanation</strong>, 147–48). But it is no<strong>to</strong>riously<br />

diffi cult <strong>to</strong> identify Wittgenstein’s own views on religion. (Was Wittgenstein<br />

a Wittgensteinian?) One recent author (Vasiliou, “Wittgenstein,” 36) suggests<br />

that Wittgenstein did not entirely reject a realist construal of religious<br />

language, although he did reject the idea that religious propositions are held<br />

<strong>to</strong> be true for the same kinds of reasons as scientifi c propositions.<br />

19. Phillips suggests that when religious propositions are taken <strong>to</strong> be explana<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

hypotheses, this represents a kind of “superstition” rather than “religion”<br />

(Religion without <strong>Explanation</strong>, 41; see also the same author’s Hermeneutics<br />

of Contemplation, 162–67).<br />

20. Among contemporary discussions of religious explanations, Michael Banner’s<br />

The Justifi cation of Science <strong>and</strong> the Rationality of Religious Belief is