- Page 1 and 2:

THE NORDICCOUNTRIES ANDTHE EUROPEAN

- Page 3 and 4:

Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom

- Page 5 and 6:

The Nordic Countries andthe Europea

- Page 7 and 8:

The Nordic Countries andthe Europea

- Page 9 and 10:

ContentsPrefacexiiAbbreviations and

- Page 11 and 12:

CONTENTSII. The European security c

- Page 13 and 14:

CONTENTSII. The small arms and ligh

- Page 15 and 16:

CONTENTSII. Iceland and the emergen

- Page 17:

PREFACEThe conference on the Nordic

- Page 20 and 21:

2 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESDP

- Page 22 and 23:

4 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESDP

- Page 24 and 25:

6 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESDP

- Page 26 and 27:

8 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESDP

- Page 28 and 29:

10 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 30 and 31:

12 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 32 and 33:

14 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 34 and 35:

16 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 36 and 37:

18 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 38 and 39:

20 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 40 and 41:

22 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 42 and 43:

24 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 44 and 45:

26 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES AND THE ESD

- Page 47 and 48:

Editor’s remarksGunilla HerolfPar

- Page 49 and 50:

EDITOR’S REMARKS 31which the vari

- Page 51 and 52:

EDITOR’S REMARKS 33mark as well s

- Page 53 and 54:

EDITOR’S REMARKS 35The Europeaniz

- Page 55 and 56:

1. Denmark and the European Securit

- Page 57 and 58:

DENMARK AND THE ESDP 39European def

- Page 59 and 60:

DENMARK AND THE ESDP 41safely leave

- Page 61 and 62:

DENMARK AND THE ESDP 43motions to t

- Page 63 and 64:

DENMARK AND THE ESDP 45effective

- Page 65 and 66:

DENMARK AND THE ESDP 47connected an

- Page 70 and 71:

52 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 72 and 73:

54 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 74 and 75:

56 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 76 and 77:

58 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 78 and 79:

60 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 80 and 81:

62 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 82 and 83:

64 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 84 and 85:

66 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 86 and 87:

68 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 88 and 89:

70 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 90 and 91:

72 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 92 and 93:

74 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 94 and 95:

76 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 96 and 97:

78 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 98 and 99:

80 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 100 and 101:

82 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 102 and 103:

84 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 104 and 105:

86 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 106 and 107:

88 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 108 and 109:

90 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 110 and 111:

92 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 112 and 113:

94 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 114 and 115:

96 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 116 and 117:

98 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLIT

- Page 118 and 119:

100 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLI

- Page 120 and 121:

102 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLI

- Page 122 and 123:

104 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLI

- Page 124 and 125:

106 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLI

- Page 126 and 127:

108 INSTITUTIONAL AND NATIONAL POLI

- Page 129:

Part IINational defence and Europea

- Page 132 and 133:

114 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 134 and 135:

116 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 137 and 138:

6. The impact of EU capability targ

- Page 139 and 140:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 141 and 142:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 143 and 144:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 145 and 146:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 147 and 148:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 149 and 150:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 151 and 152:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 153 and 154:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 155 and 156:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 157 and 158:

CAPABILITY TARGETS AND OPERATIONAL

- Page 159 and 160:

7. The impact of EU capability targ

- Page 161 and 162:

THE CASE OF SWEDEN 143Government ha

- Page 163 and 164:

THE CASE OF SWEDEN 145immediate reg

- Page 165 and 166:

THE CASE OF SWEDEN 147SAF Headquart

- Page 167 and 168:

THE CASE OF SWEDEN 149the navy will

- Page 169 and 170:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 151

- Page 171 and 172:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 153

- Page 173 and 174:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 155

- Page 175 and 176:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 157

- Page 177 and 178:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 159

- Page 179 and 180:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 161

- Page 181 and 182:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 163

- Page 183 and 184:

‘NOT ONLY, BUT ALSO NORDIC’ 165

- Page 185 and 186:

9. Hardware politics, ‘hard polit

- Page 187 and 188:

HARDWARE POLITICS 169Sweden’s sec

- Page 189 and 190:

HARDWARE POLITICS 171the exploitati

- Page 191 and 192:

HARDWARE POLITICS 173share of Finla

- Page 193 and 194: HARDWARE POLITICS 175and procuremen

- Page 195 and 196: HARDWARE POLITICS 177of internation

- Page 197 and 198: HARDWARE POLITICS 179reluctant to a

- Page 199 and 200: HARDWARE POLITICS 181EU ambitions a

- Page 201 and 202: HARDWARE POLITICS 183Nordic armamen

- Page 203 and 204: 10. The Nordic attitude to and role

- Page 205 and 206: DEFENCE INDUSTRIAL COLLABORATION 18

- Page 207 and 208: DEFENCE INDUSTRIAL COLLABORATION 18

- Page 209 and 210: DEFENCE INDUSTRIAL COLLABORATION 19

- Page 211: Part IIINordic handling of the broa

- Page 214 and 215: 196 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 216 and 217: 198 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 218 and 219: 200 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 220 and 221: 202 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 222 and 223: 204 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 224 and 225: 206 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 226 and 227: 208 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 228 and 229: 210 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 230 and 231: 212 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 232 and 233: 214 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 234 and 235: 216 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 236 and 237: 218 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 238 and 239: 220 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 240 and 241: 222 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

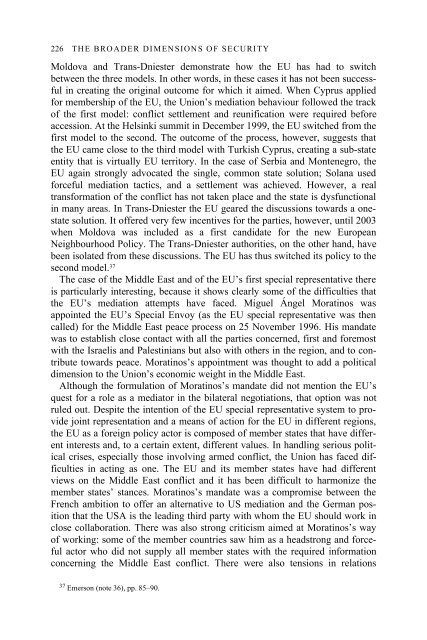

- Page 242 and 243: 224 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 246 and 247: 228 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 248 and 249: 230 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 250 and 251: 232 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 252 and 253: 13. The Nordic countries and conven

- Page 254 and 255: 236 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 256 and 257: 238 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 258 and 259: 240 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 260 and 261: 242 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 262 and 263: 244 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 264 and 265: 246 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 266 and 267: 248 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 268 and 269: 250 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 270 and 271: 14. Nordic nuclear non-proliferatio

- Page 272 and 273: 254 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 274 and 275: 256 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 276 and 277: 258 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 278 and 279: 260 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 280 and 281: 262 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 282 and 283: 264 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 284 and 285: 266 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 286 and 287: 268 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 288 and 289: 270 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 290 and 291: 272 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 292 and 293: 274 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 294 and 295:

276 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 296 and 297:

278 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 298 and 299:

280 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 300 and 301:

282 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 302 and 303:

284 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 304 and 305:

286 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 306 and 307:

16. Muddling through: how the EU is

- Page 308 and 309:

290 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 310 and 311:

292 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 312 and 313:

294 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 314 and 315:

296 THE BROADER DIMENSIONS OF SECUR

- Page 317:

Editor’s remarksAlyson J. K. Bail

- Page 320 and 321:

302 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 322 and 323:

304 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 324 and 325:

306 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 326 and 327:

308 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 328 and 329:

310 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 330 and 331:

312 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 332 and 333:

314 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 334 and 335:

316 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 336 and 337:

318 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 338 and 339:

320 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 340 and 341:

322 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 342 and 343:

324 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 344 and 345:

326 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 346 and 347:

20. Iceland and the European Securi

- Page 348 and 349:

330 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 350 and 351:

332 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 352 and 353:

334 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 354 and 355:

336 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 356 and 357:

338 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 358 and 359:

340 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 360 and 361:

342 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 362 and 363:

344 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 364 and 365:

346 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 366 and 367:

348 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 368 and 369:

350 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 370 and 371:

352 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 372 and 373:

354 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 374 and 375:

22. The Baltic states and security

- Page 376 and 377:

358 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 378 and 379:

360 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 380 and 381:

362 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 382 and 383:

23. Baltic perspectives on the Euro

- Page 384 and 385:

366 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 386 and 387:

368 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 388 and 389:

370 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 390 and 391:

372 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 392 and 393:

374 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 394 and 395:

376 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 396 and 397:

378 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 398 and 399:

380 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 400 and 401:

382 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 402 and 403:

384 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 404 and 405:

386 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 406 and 407:

388 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 408 and 409:

390 THE NORDIC COUNTRIES, THEIR REG

- Page 411 and 412:

AppendixExtracts from the Treaty Es

- Page 413 and 414:

ments, to promote measures to satis

- Page 415 and 416:

(c) strengthening systematic cooper

- Page 417 and 418:

Article III-303The Union may conclu

- Page 419 and 420:

shall carry out its tasks in liaiso

- Page 421 and 422:

EU CONSTITUTIONAL TREATY 403enhance

- Page 423 and 424:

ABOUT THE AUTHORS 405ning, Det 21.

- Page 425 and 426:

ABOUT THE AUTHORS 407Karlis Neretni

- Page 427 and 428:

ABOUT THE AUTHORS 409her publicatio

- Page 429 and 430:

INDEX 411Atlanticism 364banking 357

- Page 431 and 432:

INDEX 413Kosovo and 45Left Socialis

- Page 433 and 434:

INDEX 415Counter-Terrorism Coordina

- Page 435 and 436:

attle group 154, 181Central Union o

- Page 437 and 438:

INDEX 419Iceland Defense Force 328,

- Page 439 and 440:

INDEX 421Washington Declaration (19

- Page 441 and 442:

INDEX 423NPT (Non-Proliferation Tre

- Page 443 and 444:

ESDP and 12, 16, 19, 24, 54-55, 59,

- Page 445:

INDEX 427Vienna Documents 236Viking