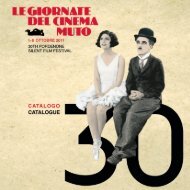

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

project – in this case, Way Down East. When one wonders how<br />

Griffith’s reputation as a director of merit suffered such a marked<br />

decline in the 1920s, films like The Love Flower provide ample<br />

evidence.<br />

Placed within the context of 1920 studio filmmaking, The Love Flower<br />

is certainly no worse than the average feature.What is dispiriting is that<br />

those aspects of the film which seem definably Griffithian reside on the<br />

same level of mediocrity as those moments which one might attribute<br />

to any journeyman director of the era. At this point, Griffith’s depiction<br />

of the woman-child as a product of nature was becoming almost<br />

parodic.Watching Carol Dempster gambol in the surf, repeatedly tossing<br />

her arms up in the spray, or demurely posed in a garden, gazing dewily<br />

at bowers of roses, one is struck by the predictable shallowness of<br />

Griffith’s conception of female innocence. The Love Flower reaches its<br />

nadir in this regard when Dempster dresses up the requisite kitten in<br />

baby clothes and then encourages a feline embrace of a tiny goat kid.<br />

Remarkably, this moment of enforced zoological affection is meant to<br />

convey the character’s emerging maternal instincts. More successful at<br />

demonstrating Margaret Bevan’s emotional growth is the brief moment<br />

when she views an obviously enamoured island couple. Rather than<br />

relying on animal substitutes, Griffith here provides undiluted desire<br />

through point of view; coupled with the lush atmospherics of the miseen-scène<br />

and Bitzer’s sense of mood, this relatively straightforward<br />

approach proves Griffith could achieve more contemporary effects.<br />

The slowly developing relationship between Margaret (Carol Dempster,<br />

whose character is referred to in some sources as Stella) and Jerry<br />

(Richard Barthelmess) finds its major obstacle in her belief that he<br />

means to aid in the capture of her father Thomas Bevan (George<br />

MacQuarrie).The fact that Margaret chooses to construe the remedy to<br />

her sexual isolation as a threat to her intense bond with her father<br />

provides a few moments of invigorating fury, most obviously when she<br />

takes an axe to Jerry’s boat and causes it to sink. But the narrative<br />

constantly distracts from the psychosexual frisson her attraction to<br />

Jerry produces by making the figure of Crane (Anders Randolf) the main<br />

object of her anger. Margaret attempts to kill Crane no less than three<br />

times, most spectacularly when she tries drowning him, creating the<br />

opportunity for some exciting underwater filming. But overall, the figure<br />

of Crane is an impediment to the film developing its most intriguing<br />

situation: Margaret’s dilemma in choosing between Jerry and her father.<br />

Rather improbably, the solution ultimately devised is that she need not<br />

make a choice, as the narrative allows her to keep both. (Even so, the<br />

film implies that the threesome can only sustain their relationship by<br />

continuing to live on the island, isolated from “the law”.) But while we<br />

are told that Margaret will return with Jerry to her father, what we are<br />

shown conveys the opposite. The film ends with the police file<br />

photograph of Thomas Bevan (pictured with his daughter, no less)<br />

marked “Dead”, followed directly by the young couple featured alone on<br />

a boat surrounded by the emblem of their relationship: the love flower.<br />

The insistence on imagery associated with Jerry and Margaret’s love<br />

further confirms the negation of the father stressed in the previous shot.<br />

91<br />

The urge to maintain the intensity of the father/daughter bond even as<br />

it is supplanted by the union of the couple results in this strangely<br />

contradictory conclusion, where visual representation refutes the<br />

assurances of the title cards.Were all of The Love Flower as suggestive<br />

as the tensions produced within its final moments, it would warrant a<br />

more extended reappraisal. – CHARLIE KEIL [DWG Project # 591]<br />

Prog. 6<br />

THE IDOL DANCER (L’idolo danzante) (D.W. Griffith, US<br />

1920)<br />

Regia/dir: D.W. Griffith; cast: Clarine Seymour, Richard Barthelmess,<br />

George MacQuarrie, Creighton Hale, Kate Bruce, Thomas Carr,<br />

Anders Randolf, Porter Strong, Herbert Sutch, Walter James,<br />

Adolphe <strong>Le</strong>stina, Florence Short, Ben Graver, Walter Kolomoku;<br />

35mm, 6818 ft., 91’ (20 fps), Patrick Stanbury Collection, London.<br />

Didascalie in inglese / English intertitles.<br />

Mi sono avvicinato a The Idol Dancer con un atteggiamento di<br />

nobile condiscendenza, cosa che si è rivelata un grosso sbaglio. Era<br />

da ingenui, infatti, pensare di poterlo liquidare come un tipico<br />

prodotto realizzato a fin di lucro, il famigerato “prodigio girato in<br />

quattro giorni” a Fort Lauderdale da Griffith in attesa di occupare<br />

il nuovo studio di Mamaroneck. Ma il film richiedeva comunque una<br />

disinvolta disanima di tipo sociologico. Meglio dunque considerarlo<br />

un prodotto in linea con la moda post-bellica <strong>del</strong>le avventure<br />

romantiche nei mari <strong>del</strong> Sud, insaporire il riferimento con una<br />

brillante citazione sulla ukulele-mania, evidenziare lo strano mix di<br />

stereotipi usati da Griffith per impastare i suoi isolani <strong>del</strong>la<br />

Polinesia, osare un ardito parallelo con Pioggia di Somerset<br />

Maugham e forse anche con Verdi dimore di W.H. Hudson, dopo di<br />

che passare subito a un Griffith migliore. Non avevo più rivisto The<br />

Idol Dancer da moltissimo tempo. Ma, se c’era un film di Griffith<br />

immune da ogni redenzione critica, questo pareva proprio essere il<br />

suo caso. E cosa mai poteva redimere una nuova visione <strong>del</strong> film?<br />

Wando, il capotribù sovrappeso con un osso infilato nel naso e due<br />

grandi teschi penzoloni sul petto a mo’ di reggiseno allentato? La<br />

schiera di interpretazioni assurde? La faccia nera di Porter Strong?<br />

La sanguinante cristianità cui facevano riferimento tutti i<br />

commentari critici?.<br />

Certo, rimaneva il ricordo persistente <strong>del</strong>la sequenza <strong>del</strong> Flatiron<br />

Building sotto la neve, ancora vivo nella mia mente a 45 anni di<br />

distanza dalla prima volta che avevo visto il film, ma ci sono limiti<br />

oltre i quali non può spingersi neanche un esperto di Griffith.<br />

<strong>Le</strong> note di presentazione, a cura di William K. Everson, che<br />

accompagnavano una riproposta <strong>del</strong> film avvenuta presso la<br />

Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society (24 aprile 1959) parevano<br />

stabilire il tono giusto:“Non avendo visto Scarlet Days, One Exciting<br />

Night né Sally of the Sawdust, non posso affermare che questo sia il<br />

GRIFFITH