SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts from the Judean Desert 213<br />

For example, in 1QS, cancellation dots were used often, either by the original scribe or<br />

someone else, to delete letters or words that were subsequently erased with a sharp instrument.<br />

Therefore, it is unclear why in 1QS VII 8 two words relating to the change of the punishment<br />

were deleted from the context by parenthesis (p. 202). It is not impossible that in this document<br />

a meaning other than erasure was attached to parenthesis, but it is more likely that the<br />

parenthesis signs were inserted by a hand other than that of the main scribe. By the same token,<br />

it is unclear why in the same text some words were canceled by cancellation dots while other<br />

elements were crossed out with a line. For example, in the same context a word was crossed out<br />

in 4QShirShabb f (4Q405) 3 i 12 (p. 200), while cancellation dots were used in the following line.<br />

Most elements to be deleted in 4QD a (4Q266) were crossed out with a line (p. 200), but there are<br />

also a few cases of dotted letters and erasures in that manuscript.<br />

Some personal preferences are recognizable in the manuscripts. Thus, 4QD a crossed out more<br />

words proportionally than other scribes (p. 200), and the scribe of 1QIsa a added more supralinear<br />

additions and used more cancellation dots than other scribes (pp. 189 ff.). In 1QS, most elements<br />

to be deleted were physically erased, while in 1QH a most elements were dotted and afterwards<br />

erased (p. 193). The same inconsistency is visible in the analysis of a single phenomenon like the<br />

correction of dittography.<br />

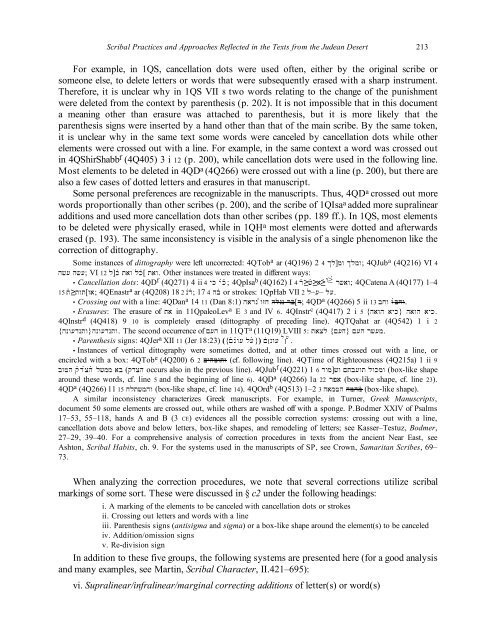

Some instances of dittography were left uncorrected: 4QTob a ar (4Q196) 2 4 ˚l]mw ˚lmw; 4QJub a (4Q216) VI 4<br />

hç[ hç[; VI 12 l]k‚ taw lk‚[ taw. Other instances were treated in different ways:<br />

• Cancellation dots: 4QD f (4Q271) 4 ii 4 yk yúkó; 4QpIsa b (4Q162) I 4 ró≥çó≥a≥ó w≥ú rçaw; 4QCatena A (4Q177) 1–4<br />

15 tó≥twt[wa; 4QEnastr a ar (4Q208) 18 2 n_d‚; 17 4 hb‚ or strokes: 1QpHab VII 2 l–[– l[.<br />

• Crossing out with a line: 4QDan a 14 11 (Dan 8:1) harn ˆwzj hlgn rb[d; 4QD a (4Q266) 5 ii 13 bjw wúbjw.<br />

• Erasures: The erasure of ta in 11QpaleoLev a E 3 and IV 6. 4QInstr c (4Q417) 2 i 5 {hawh ayk} hawh ayk.<br />

4QInstr d (4Q418) 9 10 is completely erased (dittography of preceding line). 4QTQahat ar (4Q542) 1 i 2<br />

{hnw[dntw}hnw[dntw. The second occurrence of µ[h in 11QT a (11Q19) LVIII 5: taxl {µ[h} µ[h rç[m.<br />

• Parenthesis signs: 4QJer a XII 11 (Jer 18:23) ({µónúw[ l[ó}) µ‚?nw[ l ¿ [ .<br />

• Instances of vertical dittography were sometimes dotted, and at other times crossed out with a line, or<br />

encircled with a box: 4QTob e (4Q200) 6 2 µyhmwtw (cf. following line). 4QTime of Righteousness (4Q215a) 1 ii 9<br />

bwfh qódúxhó lçmm ab (qdxh occurs also in the previous line). 4QJub f (4Q221) 1 6 rwm]çw µtb[wt lwkmw (box-like shape<br />

around these words, cf. line 5 and the beginning of line 6). 4QD a (4Q266) 1a 22 rpa (box-like shape, cf. line 23).<br />

4QD a (4Q266) 11 15 jltçmhw (box-like shape, cf. line 14). 4QOrd b (4Q513) 1–2 3 hamfh hmhm‚ (box-like shape).<br />

A similar inconsistency characterizes Greek manuscripts. For example, in Turner, Greek Manuscripts,<br />

document 50 some elements are crossed out, while others are washed off with a sponge. P.Bodmer XXIV of Psalms<br />

17–53, 55–118, hands A and B (3 CE) evidences all the possible correction systems: crossing out with a line,<br />

cancellation dots above and below letters, box-like shapes, and remodeling of letters; see Kasser–Testuz, Bodmer,<br />

27–29, 39–40. For a comprehensive analysis of correction procedures in texts from the ancient Near East, see<br />

Ashton, Scribal Habits, ch. 9. For the systems used in the manuscripts of SP, see Crown, Samaritan Scribes, 69–<br />

73.<br />

When analyzing the correction procedures, we note that several corrections utilize scribal<br />

markings of some sort. These were discussed in § c2 under the following headings:<br />

i. A marking of the elements to be canceled with cancellation dots or strokes<br />

ii. Crossing out letters and words with a line<br />

iii. Parenthesis signs (antisigma and sigma) or a box-like shape around the element(s) to be canceled<br />

iv. Addition/omission signs<br />

v. Re-division sign<br />

In addition to these five groups, the following systems are presented here (for a good analysis<br />

and many examples, see Martin, Scribal Character, II.421–695):<br />

vi. Supralinear/infralinear/marginal correcting additions of letter(s) or word(s)