SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

68 Chapter 4: Technical Aspects of Scroll Writing<br />

verso 4Q506 4QpapDibHam c y y<br />

recto 4Q509 4QpapPrFêtes c y y<br />

verso 4Q496 4QpapM f y y<br />

If the understanding of ‘recto’ and ‘verso’ is correct in the texts recorded in this table, the<br />

sectarian use of the material is both primary and secondary. In other words, sectarian scrolls of<br />

various natures were subsequently reused by others, among them sectarian scribes. The fragment<br />

on which the Hebrew 4QNarrative Work and Prayer (4Q460 9) appears on the recto, and<br />

4QAccount gr (4Q350; both: DJD XXXVI) on the verso is probably irrelevant to this<br />

analysis. 124<br />

It should be noticed that both copies of 4QRitPur (A [4Q414]; B [4Q512]) were written on<br />

the verso of other texts.<br />

(2) Palimpsests<br />

A palimpsest is a piece of material (papyrus or leather) which has been used a second time by<br />

writing over the original text, after it had been partially or mostly erased or washed off (in the<br />

case of papyri). Thus, the long Ahiqar papyrus from Elephantine (fifth century BCE) was partly<br />

written on sheets of papyrus which had contained a customs account and which were<br />

subsequently washed off (Porten–Yardeni, TAD 3.23). Among the Egyptian Aramaic papyri,<br />

several such palimpsests were detected (Porten–Yardeni, TAD 3.xiii). For other Egyptian<br />

parallels, see C7erny, Paper, 23 and in greater detail Caminos, “Reuse of Papyrus.”<br />

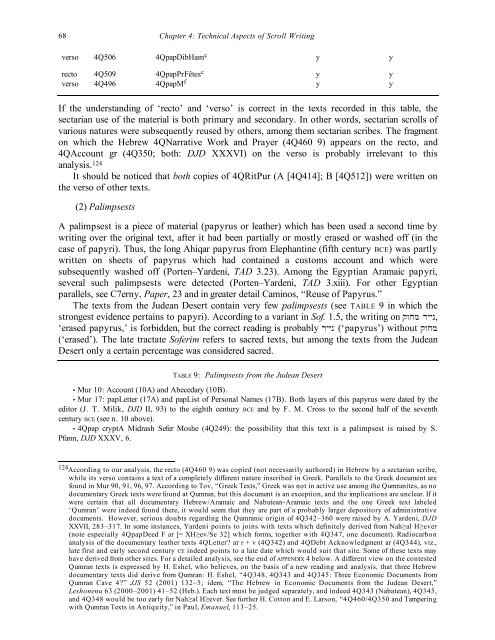

The texts from the Judean Desert contain very few palimpsests (see TABLE 9 in which the<br />

strongest evidence pertains to papyri). According to a variant in Sof. 1.5, the writing on qwjm ryyn,<br />

‘erased papyrus,’ is forbidden, but the correct reading is probably ryyn (‘papyrus’) without qwjm<br />

(‘erased’). The late tractate Soferim refers to sacred texts, but among the texts from the Judean<br />

Desert only a certain percentage was considered sacred.<br />

TABLE 9: Palimpsests from the Judean Desert<br />

• Mur 10: Account (10A) and Abecedary (10B).<br />

• Mur 17: papLetter (17A) and papList of Personal Names (17B). Both layers of this papyrus were dated by the<br />

editor (J. T. Milik, DJD II, 93) to the eighth century BCE and by F. M. Cross to the second half of the seventh<br />

century BCE (see n. 10 above).<br />

• 4Qpap cryptA Midrash Sefer Moshe (4Q249): the possibility that this text is a palimpsest is raised by S.<br />

Pfann, DJD XXXV, 6.<br />

124 According to our analysis, the recto (4Q460 9) was copied (not necessarily authored) in Hebrew by a sectarian scribe,<br />

while its verso contains a text of a completely different nature inscribed in Greek. Parallels to the Greek document are<br />

found in Mur 90, 91, 96, 97. According to <strong>Tov</strong>, “Greek Texts,” Greek was not in active use among the Qumranites, as no<br />

documentary Greek texts were found at Qumran, but this document is an exception, and the implications are unclear. If it<br />

were certain that all documentary Hebrew/Aramaic and Nabatean-Aramaic texts and the one Greek text labeled<br />

‘Qumran’ were indeed found there, it would seem that they are part of a probably larger depository of administrative<br />

documents. However, serious doubts regarding the Qumranic origin of 4Q342–360 were raised by A. Yardeni, DJD<br />

XXVII, 283–317. In some instances, Yardeni points to joins with texts which definitely derived from Nah≥al H≥ever<br />

(note especially 4QpapDeed F ar [= XH≥ev/Se 32] which forms, together with 4Q347, one document). Radiocarbon<br />

analysis of the documentary leather texts 4QLetter? ar r + v (4Q342) and 4QDebt Acknowledgment ar (4Q344), viz.,<br />

late first and early second century CE indeed points to a late date which would suit that site. Some of these texts may<br />

have derived from other sites. For a detailed analysis, see the end of APPENDIX 4 below. A different view on the contested<br />

Qumran texts is expressed by H. Eshel, who believes, on the basis of a new reading and analysis, that three Hebrew<br />

documentary texts did derive from Qumran: H. Eshel, “4Q348, 4Q343 and 4Q345: Three Economic Documents from<br />

Qumran Cave 4?” JJS 52 (2001) 132–5; idem, “The Hebrew in Economic Documents from the Judean Desert,”<br />

Leshonenu 63 (2000–2001) 41–52 (Heb.). Each text must be judged separately, and indeed 4Q343 (Nabatean), 4Q345,<br />

and 4Q348 would be too early for Nah≥al H≥ever. See further H. Cotton and E. Larson, “4Q460/4Q350 and Tampering<br />

with Qumran Texts in Antiquity,” in Paul, <strong>Emanuel</strong>, 113–25.