SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

SCRIBAL PRACTICES AND APPROACHE S ... - Emanuel Tov

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts from the Judean Desert 21<br />

second person masculine singular as –k (except for his last two columns), while scribe C used plene forms, e.g.<br />

hkklm, mlkkh, etc.<br />

• 1QS VII 1: In the running text, wl rça rbd lwkl wa was written by scribe B, followed by a five-letter word, now<br />

erased, while the cancellation dots above and below were left. In line 21 scribe B likewise wrote several words in the<br />

running text. The work of scribes A and B in 1QS VII–VIII was described in detail by Martin, Scribal Hands, I.43–<br />

56 and Metso, Community Rule, 95–105. According to Martin, I.55–56, this cooperation continued in 1QSa–1QSb.<br />

• 4QTanh≥ (4Q176): For the details regarding the distinction between the two hands, see Strugnell, “Notes,”<br />

229 and pl. II.<br />

• 4QJuba (4Q216): The change of hands between scribes A and B is clearly visible in frg. 12 which forms the<br />

dividing line between the segments written by the two scribes. This fragment consists of the last column of a sheet<br />

written by scribe A and the first column of a sheet by scribe B, stitched together by a thread. According to J.<br />

VanderKam and J. T. Milik, who published this text in DJD XIII, the beginning of the scroll written by scribe A<br />

represents a repair sheet, but it seems equally possible that the scroll was written by two different scribes.<br />

• 4QCommunal Confession (4Q393): Frgs. 1–2 i–ii are composed of segments of two sheets sewn together,<br />

although they are of a different nature: the handwriting on the two sheets differs as does the number of lines (the right<br />

hand sheet has one line more than the left hand sheet). The relation between the content of the two sheets is unclear.<br />

• 4QApocryphal Psalm and Prayer (4Q448); illustr. 11): 11 This small document was written by scribes A (col. I)<br />

and B (cols. II and III).<br />

• 11QTa (11Q19): This scroll was written by scribes A (cols. I–V) and B (cols. VI–LXVII). Yadin, Temple<br />

Scroll, I.11–12 believes that sheet 1 (cols. I–V) was a repair sheet replacing the original sheet (ch. 4i). Scribe A left<br />

excessively large spaces between the words.<br />

• 8H≥evXIIgr: Scribe B started in the middle of Zechariah. For a description of the differences between the two<br />

hands relating to material, letters, and scribal practices, see <strong>Tov</strong>, DJD VIII, 13.<br />

Whether in these cases the change of hands indicates a collaboration of some kind between scribes,<br />

possibly within the framework of a scribal school (cf. ch. 8a), is difficult to ascertain. Sometimes<br />

(4QJub a [4Q216]) the second hand may reflect a corrective passage or a repair sheet. The situation<br />

becomes even more difficult to understand when the hand of a scribe B or C is recognized not only<br />

in independently written segments, but also in the corrections of the work of a scribe A. Thus,<br />

according to Martin, Scribal Character, I.63, scribe C of 1QH a corrected the work of scribe A,<br />

while scribe B corrected that of both scribes A and C.<br />

When scribes recorded their own names, as in several of the documentary texts, identity can<br />

easily be established. Thus Matat son of Simeon, who wrote XH≥ev/Se 13, also wrote 5/6H≥ev<br />

47b and XH≥ev/Se 7 (A. Yardeni, DJD XXVII, 65). However, this procedure reflects the<br />

exception rather than the rule, and in literary texts no names were indicated.<br />

It is difficult to identify scribal hands by an analysis of handwriting and other scribal features,<br />

partly because of the formal character of the handwriting of many texts. However, if this<br />

uncertainty is taken into consideration, one notes that among the Qumran manuscripts very few<br />

individual scribes can be identified as having copied more than one manuscript. It stands to reason<br />

that several of the preserved manuscripts were written by the same scribe, but we are not able<br />

easily to detect such links between individual manuscripts, partly because of the fragmentary<br />

status of the evidence and partly because of the often formal character of the handwriting. For<br />

possible identifications, see TABLE 2. Further research may lead to more scribal identifications<br />

than are known today. In the meantime we are unable to perform comparative studies of scrolls<br />

written by the same scribe, such as that carried out by W. A. Johnson (The Literary Papyrus Roll)<br />

for the Oxyrhynchus Greek papyri from the second to fourth century CE.<br />

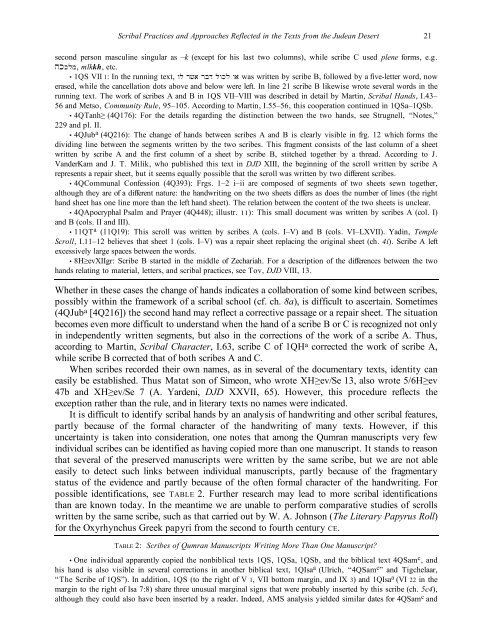

TABLE 2: Scribes of Qumran Manuscripts Writing More Than One Manuscript?<br />

• One individual apparently copied the nonbiblical texts 1QS, 1QSa, 1QSb, and the biblical text 4QSam c , and<br />

his hand is also visible in several corrections in another biblical text, 1QIsa a (Ulrich, “4QSam c ” and Tigchelaar,<br />

“The Scribe of 1QS”). In addition, 1QS (to the right of V 1, VII bottom margin, and IX 3) and 1QIsa a (VI 22 in the<br />

margin to the right of Isa 7:8) share three unusual marginal signs that were probably inserted by this scribe (ch. 5c4),<br />

although they could also have been inserted by a reader. Indeed, AMS analysis yielded similar dates for 4QSam c and