- Page 2:

SHAPE

- Page 5 and 6:

( 2006 Massachusetts Institute of T

- Page 8:

Contents Acknowledgments ix INTRODU

- Page 12 and 13: INTRODUCTION: TELL ME ALL ABOUT IT

- Page 14 and 15: 3 Answer Number One—What Do You S

- Page 16 and 17: 5 Answer Number One—What Do You S

- Page 18 and 19: 7 Answer Number One—What Do You S

- Page 20 and 21: 9 Answer Number Two—Three More Wa

- Page 22 and 23: 11 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 24 and 25: 13 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 26 and 27: 15 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 28 and 29: 17 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 30 and 31: 19 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 32 and 33: 21 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 34 and 35: 23 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 36 and 37: 25 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 38 and 39: 27 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 40 and 41: 29 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 42 and 43: 31 Answer Number Two—Three More W

- Page 44 and 45: 33 Trying to Be Clear Points aren

- Page 46 and 47: 35 Trying to Be Clear and twenty-fo

- Page 48 and 49: 37 Trying to Be Clear things look.

- Page 50 and 51: 39 Trying to Be Clear on correspond

- Page 52 and 53: 41 Tables, Teacher’s Desks, and R

- Page 54 and 55: 43 Tables, Teacher’s Desks, and R

- Page 56 and 57: 45 It Always Pays to Look Again In

- Page 58 and 59: 47 Background always more when you

- Page 60 and 61: 49 Background Getting it first and

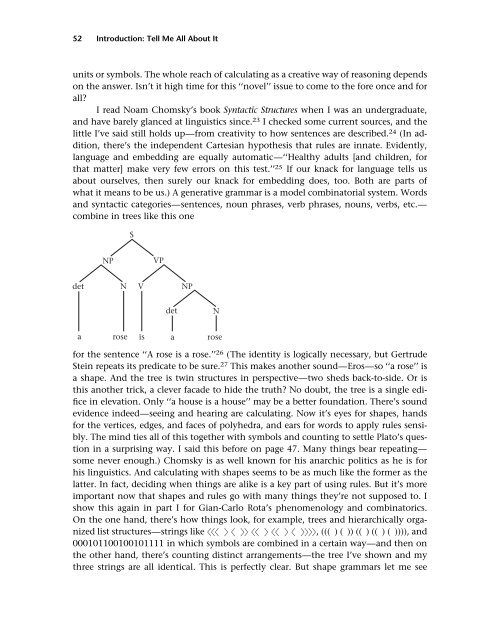

- Page 64 and 65: 53 Background and count as I please

- Page 66 and 67: 55 Background and time. The way Eul

- Page 68 and 69: 57 Background them apart—a triang

- Page 70: 59 Background without ‘‘agreeme

- Page 73 and 74: 62 I What Makes It Visual? (2) What

- Page 75 and 76: 64 I What Makes It Visual? Whenever

- Page 77 and 78: 66 I What Makes It Visual? calculat

- Page 79 and 80: 68 I What Makes It Visual? And my r

- Page 81 and 82: 70 I What Makes It Visual? more tha

- Page 83 and 84: 72 I What Makes It Visual? Table 1

- Page 85 and 86: 74 I What Makes It Visual? but neve

- Page 87 and 88: 76 I What Makes It Visual? may be f

- Page 89 and 90: 78 I What Makes It Visual? formula

- Page 91 and 92: 80 I What Makes It Visual? But what

- Page 93 and 94: 82 I What Makes It Visual? they pro

- Page 95 and 96: 84 I What Makes It Visual? The one

- Page 97 and 98: 86 I What Makes It Visual? I see a

- Page 99 and 100: 88 I What Makes It Visual? But this

- Page 101 and 102: 90 I What Makes It Visual? contains

- Page 103 and 104: 92 I What Makes It Visual? and othe

- Page 105 and 106: 94 I What Makes It Visual? The lett

- Page 107 and 108: 96 I What Makes It Visual? and corr

- Page 109 and 110: 98 I What Makes It Visual? (Is hh i

- Page 111 and 112: 100 I What Makes It Visual? and the

- Page 113 and 114:

102 I What Makes It Visual? There

- Page 115 and 116:

104 I What Makes It Visual? to the

- Page 117 and 118:

106 I What Makes It Visual? Table 2

- Page 119 and 120:

108 I What Makes It Visual? is trie

- Page 121 and 122:

110 I What Makes It Visual? artifac

- Page 123 and 124:

112 I What Makes It Visual? and thi

- Page 125 and 126:

114 I What Makes It Visual? and the

- Page 127 and 128:

116 I What Makes It Visual? looks l

- Page 129 and 130:

118 I What Makes It Visual? and the

- Page 131 and 132:

120 I What Makes It Visual? when th

- Page 133 and 134:

122 I What Makes It Visual? until t

- Page 135 and 136:

124 I What Makes It Visual? The fir

- Page 137 and 138:

126 I What Makes It Visual? What Sc

- Page 139 and 140:

128 I What Makes It Visual? Here, g

- Page 141 and 142:

130 I What Makes It Visual? be desc

- Page 143 and 144:

132 I What Makes It Visual? An addi

- Page 145 and 146:

134 I What Makes It Visual? forget

- Page 147 and 148:

136 I What Makes It Visual? that bl

- Page 149 and 150:

138 I What Makes It Visual? Why is

- Page 151 and 152:

140 I What Makes It Visual? see wha

- Page 153 and 154:

142 I What Makes It Visual? to calc

- Page 155 and 156:

144 I What Makes It Visual? How cav

- Page 157 and 158:

146 I What Makes It Visual? togethe

- Page 159 and 160:

148 I What Makes It Visual? and six

- Page 161 and 162:

150 I What Makes It Visual? and its

- Page 163 and 164:

152 I What Makes It Visual? these h

- Page 165 and 166:

154 I What Makes It Visual? So how

- Page 167 and 168:

156 I What Makes It Visual? (TRI(XY

- Page 169 and 170:

158 I What Makes It Visual? The fir

- Page 171 and 172:

160 II Seeing How It Works was thre

- Page 173 and 174:

162 II Seeing How It Works and lowe

- Page 175 and 176:

164 II Seeing How It Works Back to

- Page 177 and 178:

166 II Seeing How It Works Divide e

- Page 179 and 180:

168 II Seeing How It Works There ar

- Page 181 and 182:

170 II Seeing How It Works while th

- Page 183 and 184:

172 II Seeing How It Works there ar

- Page 185 and 186:

174 II Seeing How It Works This has

- Page 187 and 188:

176 II Seeing How It Works And noti

- Page 189 and 190:

178 II Seeing How It Works looks ex

- Page 191 and 192:

180 II Seeing How It Works meaning.

- Page 193 and 194:

182 II Seeing How It Works and the

- Page 195 and 196:

184 II Seeing How It Works Embeddin

- Page 197 and 198:

186 II Seeing How It Works both of

- Page 199 and 200:

188 II Seeing How It Works but in a

- Page 201 and 202:

190 II Seeing How It Works It’s e

- Page 203 and 204:

192 II Seeing How It Works of one i

- Page 205 and 206:

194 II Seeing How It Works how it w

- Page 207 and 208:

196 II Seeing How It Works Table 7

- Page 209 and 210:

198 II Seeing How It Works of these

- Page 211 and 212:

200 II Seeing How It Works maximal

- Page 213 and 214:

202 II Seeing How It Works They’r

- Page 215 and 216:

204 II Seeing How It Works So, bðA

- Page 217 and 218:

206 II Seeing How It Works made up

- Page 219 and 220:

208 II Seeing How It Works boundary

- Page 221 and 222:

210 II Seeing How It Works First, t

- Page 223 and 224:

212 II Seeing How It Works topology

- Page 225 and 226:

214 II Seeing How It Works This has

- Page 227 and 228:

216 II Seeing How It Works where po

- Page 229 and 230:

218 II Seeing How It Works Operatio

- Page 231 and 232:

220 II Seeing How It Works is part

- Page 233 and 234:

222 II Seeing How It Works In parti

- Page 235 and 236:

224 II Seeing How It Works suggest

- Page 237 and 238:

226 II Seeing How It Works intricat

- Page 239 and 240:

228 II Seeing How It Works see what

- Page 241 and 242:

230 II Seeing How It Works to show

- Page 243 and 244:

232 II Seeing How It Works It’s a

- Page 245 and 246:

234 II Seeing How It Works that can

- Page 247 and 248:

236 II Seeing How It Works But supp

- Page 249 and 250:

238 II Seeing How It Works And toge

- Page 251 and 252:

240 II Seeing How It Works with poi

- Page 253 and 254:

242 II Seeing How It Works It’s f

- Page 255 and 256:

244 II Seeing How It Works to limit

- Page 257 and 258:

246 II Seeing How It Works and two

- Page 259 and 260:

248 II Seeing How It Works And the

- Page 261 and 262:

250 II Seeing How It Works (inducti

- Page 263 and 264:

252 II Seeing How It Works Two seco

- Page 265 and 266:

254 II Seeing How It Works Or I can

- Page 267 and 268:

256 II Seeing How It Works I can’

- Page 269 and 270:

258 II Seeing How It Works —and s

- Page 271 and 272:

260 II Seeing How It Works Now, no

- Page 273 and 274:

262 II Seeing How It Works up of se

- Page 275 and 276:

264 II Seeing How It Works These co

- Page 277 and 278:

266 II Seeing How It Works Why? The

- Page 279 and 280:

268 II Seeing How It Works and its

- Page 281 and 282:

270 II Seeing How It Works square f

- Page 283 and 284:

272 II Seeing How It Works descript

- Page 285 and 286:

274 II Seeing How It Works produce

- Page 287 and 288:

276 II Seeing How It Works points.

- Page 289 and 290:

278 II Seeing How It Works x fi y t

- Page 291 and 292:

280 II Seeing How It Works Indeterm

- Page 293 and 294:

282 II Seeing How It Works Or I can

- Page 295 and 296:

284 II Seeing How It Works applies

- Page 297 and 298:

286 II Seeing How It Works the same

- Page 299 and 300:

288 II Seeing How It Works in terms

- Page 301 and 302:

290 II Seeing How It Works It’s e

- Page 303 and 304:

292 II Seeing How It Works If a rul

- Page 305 and 306:

294 II Seeing How It Works But then

- Page 307 and 308:

296 II Seeing How It Works And, cer

- Page 309 and 310:

298 II Seeing How It Works are all

- Page 311 and 312:

300 II Seeing How It Works combine

- Page 313 and 314:

302 II Seeing How It Works In fact,

- Page 315 and 316:

304 II Seeing How It Works next pap

- Page 317 and 318:

306 II Seeing How It Works Table 12

- Page 319 and 320:

308 II Seeing How It Works initial

- Page 321 and 322:

310 II Seeing How It Works Kinemati

- Page 323 and 324:

312 III Using It to Design (3) desi

- Page 325 and 326:

314 III Using It to Design does mor

- Page 327 and 328:

316 III Using It to Design that I d

- Page 329 and 330:

318 III Using It to Design don’t

- Page 331 and 332:

320 III Using It to Design fix the

- Page 333 and 334:

322 III Using It to Design Figure 1

- Page 335 and 336:

324 III Using It to Design —divid

- Page 337 and 338:

326 III Using It to Design Perhaps

- Page 339 and 340:

328 III Using It to Design I seem t

- Page 341 and 342:

330 III Using It to Design Figure 3

- Page 343 and 344:

332 III Using It to Design Then the

- Page 345 and 346:

334 III Using It to Design and ‘

- Page 347 and 348:

336 III Using It to Design Figure 4

- Page 349 and 350:

338 III Using It to Design But this

- Page 351 and 352:

340 III Using It to Design but occa

- Page 353 and 354:

342 III Using It to Design numbers

- Page 355 and 356:

344 III Using It to Design to start

- Page 357 and 358:

346 III Using It to Design The rule

- Page 359 and 360:

348 III Using It to Design Everythi

- Page 361 and 362:

350 III Using It to Design Figure 5

- Page 363 and 364:

352 III Using It to Design Let’s

- Page 365 and 366:

354 III Using It to Design ever hav

- Page 367 and 368:

356 III Using It to Design (2) Furt

- Page 369 and 370:

358 III Using It to Design that wor

- Page 371 and 372:

360 III Using It to Design with the

- Page 373 and 374:

362 III Using It to Design are equi

- Page 375 and 376:

364 III Using It to Design and in f

- Page 377 and 378:

366 III Using It to Design to the p

- Page 379 and 380:

368 III Using It to Design rules th

- Page 381 and 382:

370 III Using It to Design x fi bð

- Page 383 and 384:

372 III Using It to Design These we

- Page 385 and 386:

374 III Using It to Design easy to

- Page 387 and 388:

376 III Using It to Design and spir

- Page 389 and 390:

378 III Using It to Design I said I

- Page 391 and 392:

380 III Using It to Design include

- Page 393 and 394:

382 III Using It to Design x fi x i

- Page 395 and 396:

384 III Using It to Design It’s g

- Page 397 and 398:

386 III Using It to Design take car

- Page 399 and 400:

388 III Using It to Design wealth o

- Page 402 and 403:

Notes Introduction 1. S. Pinker, Th

- Page 404 and 405:

393 Notes to pp. 48-50 Langer’s d

- Page 406 and 407:

395 Notes to pp. 51-55 19. H. L. Dr

- Page 408 and 409:

397 Notes to p. 156 9. C. Alexander

- Page 410 and 411:

399 Notes to p. 304 of lowest-level

- Page 412 and 413:

401 Notes to p. 305 24. The ‘‘n

- Page 414 and 415:

403 Notes to pp. 306-387 35. G. Sti

- Page 416 and 417:

405 Notes to pp. 388-389 M. A. Bode

- Page 418:

407 Notes to p. 389 The essence in

- Page 421 and 422:

410 Index Aristotle, 81, 167, 337 A

- Page 423 and 424:

412 Index creativity and (cont.) re

- Page 425 and 426:

414 Index greatest lower bound, 224

- Page 427 and 428:

416 Index maximal elements and basi

- Page 429 and 430:

418 Index Quine, W. V., 57, 58, 210

- Page 431 and 432:

420 Index shape grammars (cont.) an

- Page 433:

422 Index Van Gogh, V., 403n1 Vanto