ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

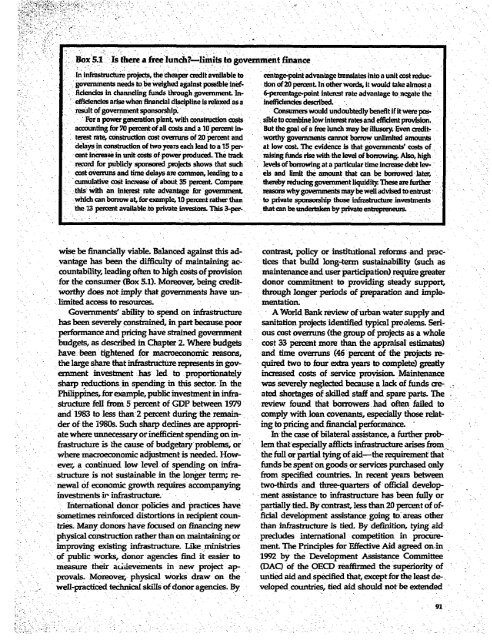

Box 5.1 Is there a free lunch?-limits to govemment finance<br />

In infrastructure projects, the cheaper credit available to centage-point advantage tmnslates into a unit cost reducgover:unents<br />

needs to be weighed against possible inef- don of 20 percent. In other words, it would take almost a<br />

ficiencies in channeling funds through government. in- 6-percentage-point Interest rate advantage to negate the<br />

efficiencies arise when financial dWipline is relaxed as a inefficiencies described.<br />

result of government sponsorship.<br />

Consumers would undoubtedly benefit if it were pos-<br />

For n powergeneration plant, with construction costs sible to combine low interest rates and efficient provision.<br />

acounting for 70 percent of ail costs and a 10 pent In- But the goal of a free lunch may be illusory. Even creditterest<br />

rate, construction cost overnuns of 20 percent and worthy govenuments cannot borrow unlimited amounts<br />

delays in construction of two years each lead to a 15 per- at low cost. The evidence Is that governments' costs of<br />

cent increase in unit costs of power produced. The track raising funds rise with the level of bornwins& Also, high<br />

record for publicly sponsored projectshows that such levels of bormroing at a particular time increase debt levcost<br />

overruns and time delays are conunon, leading to a els and limit the amount that can be borrowed later,<br />

cumulative cost increase of about 35 percent Compare thereby redudng goverunent liquidity. These are further<br />

this with an interest-rate advantage for governnent, reasonswhygovenmmentsmaybeweBladvisedtoentrust<br />

which can borrow at, for example, 10 percent rather than to private sponsorshlp those infrastructure investments<br />

the 13 percent available to private investors. This 3-per- that can be undertaken by private entrepreneurs.<br />

vise be financially viable Balanced against this ad- contrast, policy or institutional reforms and prcvantage<br />

has been the difficulty of maintaining ac- tices that build long-term sustainability (such as<br />

countability, leading often to high costs of provision maintenance and user participation) require greater<br />

for the consumer (Box 5.1). Moreover, being credit- donor commitment to providing steady support,<br />

worthy does not imply that governments have un- through longer-periods of preparation and implelimited<br />

access to resources.<br />

mentation.<br />

Governments' ability to spend on infrastructure A World Bank review of urban water supply and<br />

has been severely constrained, in part because poor sanitation projects identified typical proolems. Seriperformance<br />

and pncing have strained govemment ous cost overuns (the group of projects as a whole<br />

budgets, as described in Chapter 2. Where budgets cost 33 percent more than the appraisal estimates)<br />

have been tightened for macroeconomic reasons, and time overruns (46 percent of the projects rethe<br />

large share that infrastructure represents in gov- quired two to four extra years to complete) greatly<br />

ernment investment has led to proportionately increased costs of service provision. Maintenance<br />

sharp reductions in spending in this sector. In the was severely neglected because a lack of funds cre-<br />

Philippines, for example, public mivestment in infra- ated shortages of skilled staff and spare parts. The<br />

structure fell from 5 percent of GDP between 1979 review found that borrowers had often failed to<br />

and 1983 to less than 2 percent during the remain- comply with loan covenants, especially those relatder<br />

of the 1980s. Such sharp declines are appropni- ing to prcing and financial performance.<br />

ate where unnecessary or inefficient spending on in- hn the case of bilateral assistance, a furither probfrastructure<br />

is the cause of budgetary problems, or' lem that especially afflicts infrastructure arises from<br />

where macroeconomic adjustment is needed. How- the full or partial tying of aid-the requirement that<br />

ever, a continued low level of spending on infra- funds be spent on goods or services purchased only<br />

structure is not sustainable in the long term; re- from specified countries. In recent years between<br />

newal of economic growth requires accompanying two-thirds and three-quarters of official developinvestments<br />

ir infrastructure.<br />

ment assistance to infrastructure has been fully or<br />

International donor policies and practices have parally tied. By contrast, less than 20 percent of ofsometimes<br />

reinforced distortions in recipient coun- ficial development assistance going to areas other<br />

tries. Many donors have focused on financing new than ifrastructure is tied. By definition, tying aid<br />

physial construction rather than on maintaining or precludes international competition in procureimproving<br />

existing infrastructure Like mmistries menL The Principles for Effective Aid agreed on in<br />

of public works, donor agencies find it easier to 1992 by the Development Assistance Committee<br />

measure their acidevements in new project ap- (DAC) of the OECD reaffirmed the superiority of<br />

provals. Moreover, physical works draw on the untied aid and specfied that, except for the least de-.<br />

well-practiced technical skills of donor agencies. By veloped countries, tied aid should not be extended<br />

91