ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

to this purpose without sacrificing other socially - .-..*-..<br />

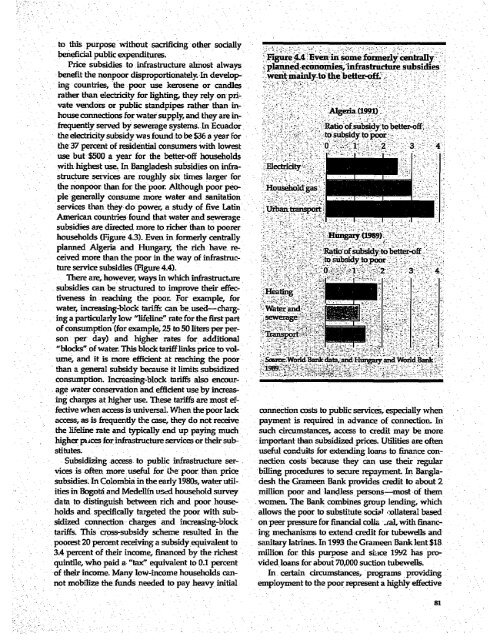

beneficial public expenditures. 4 E m s e centrally<br />

Price subsidies to infrastructure almost always plannedecnonomies,infrastructurebsubsidides<br />

benefit the nonpoor disproportionately. In develop- ' wentmainlyto the better-o'. -<br />

ing countries, the poor ue kerosene or candles<br />

rather tain electricity for lighting, they rely on pri- -.<br />

* vate vendors or public standpipes rather than inhouse<br />

connections for ater supply, and they are in- . t<br />

ge.(1:1)<br />

frequently served by sewerage systems. In Ecuador . Rt of subsidy to better-off;<br />

the electricitysubsidy was found.to be $36 a year for<br />

tossidytoporthe<br />

37 percent of residential consumers with lowest -- 0 . 1 - 3 '-<br />

use but $500 a year for the better-off households >'.-1 -.<br />

-with highest use. In Bangladesh subsidies on infra- Eleciity -<br />

structure services are roughly six times larger for<br />

the nonpoor than for the poor. Although poor peo- Hou old'gas<br />

ple generally consume more water and sanitation .<br />

services than they do power, a study of five Latn ' UrbaIrsp_ ..<br />

American countries found that water and sewerage<br />

subsidies are diected more to richer than to poorer<br />

"u":-:::'<br />

households (Figure 4.3) Even in fonnerly centraly -. -.<br />

planned Algeria and Hungary, the rich have re- . ' xauo of subsidylto better-of<br />

ceived more than the poor in the way of infrastruc- to ssidy i- to por<br />

tireservicesubsidies (Figure4.4). :. 3' 4<br />

There are, however, ways in which infrastructre, a. - V; - - ' '<br />

subsidies can be structured to improve their effecdireness<br />

in reaching the poor. For example, for<br />

-'<br />

water, increasing-block tariffs can be. used-charg- Wat aind<br />

ing a particularly low "'leline" rate for the firt part '<br />

of consumption (for example, 25 to 50 liters per per- _ ,t,<br />

son per day) and higher rates for additional .<br />

'blocks" of water. This block taiff links price to volume,<br />

and it is more efficient at reaching the poor rtdildtand HimayandWorld-Bank<br />

than a general subsidy because it limits subsidized 19e 9 '5' <<br />

consumption. Increasing-block tariffs also encourage<br />

water conservation and efficent use by increasing<br />

charges at higher use. These tariffs are most effective<br />

when access is universal. When the poor lack connection costs to public services, especially when<br />

access, as is frequently the case, they do not receive payment is required in advance of connection. In<br />

the lifeline rate and typically end up paying much such circumstances, access to credit may be more<br />

higher puces for infrastructure services or their sub- important than subsidized prices. Utilities are often<br />

stitutes-<br />

useful conduits for extending loans to finance con-<br />

Subsidizing access to public infrastructure ser-. nection costs because they can use their regular<br />

vices is often more. useful for ibe poor than price billing procedures to secure repayment In Banglasubsidies-<br />

In Colombia in the early 1980s, water u:il- desh the Grameen Bank provides credit to about 2<br />

ities in Bogoti and Medelin used household survey million poor and landless persons-most of them<br />

data to distinguish between rich and poor house- women. The Bank combines group lending, which<br />

holds and specifically targeted the poor with sub- allows the poor to substitute social oollateral based<br />

- . . sidized connection charges and increasing-block on peer pressure for financial colla -al, with financ-<br />

*: ' tariffs. This cross-subsidy scheme resulted in the ing mechanisms to extend credit for tubewells and<br />

poorest 20 percent receiving a subsidy equivalent to sanitary latrines. In 1993 the Grameen Bank lent $18<br />

* 3.4 percent of their income, financed by the richest million for this purpose and sLice 1992 has proquintile,<br />

who paid a- "tax" equivalent to 0.1 percent<br />

of their income. Many low-income households carnot<br />

mobilize the funds needed to pay heavy initial<br />

- .. . . . . .~~~~~~~~~<br />

vided loans for about 70,000 suction tubewells.<br />

In certain crcumstances, programs providing<br />

employment to the poor represent a highly effective