ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

government-owned subway system began opera- that can contest the market limits the risks of mntion,<br />

large buses became less profitable, and the rate nopoly abuse. The implication is that, absent comof<br />

return that had formerly been guaranteed to bus pelling arguments to the contrary, all new entrants<br />

companies by regulation became univiable. Efforts should be allowed to provide services, with the<br />

to maintain the rate of return by raising fares on market deciding how many providers can operate<br />

large buses caused passengers to abandon bus profitably. Potential competition is most effective<br />

transport, leading to taxi shortages, overuse of cars, where new entrants tave limited sunk costs of marand<br />

continuing congestion. ket entry-that is, when entrants.can recover their<br />

Thus, when substitutes are available, regulation investments by selling their assets if they decide to<br />

can have especially perverse effects. To shore up re-. pull out of the business. Technological change and<br />

turns in tlte regulated sector, regulators often ex- easing of regulatory constraints are permitting<br />

tend their reach to sectors in which natural monop greater contestability<br />

oly elements are weak. It -is far better in these ' Much of the experience with direct competition<br />

crcumstances to allow the competition from sub- in infrastructure is relatively new, but the results<br />

stitutes to discipline the conduct of the alleged validate the benefits of competition. Systematic evimonopolisL<br />

dence of efficiency gains from greater competition<br />

Co*petitin i. i.frastructe .narket- '.<br />

-comes mainly from the United States, which, after<br />

CoipeStitioi in inJimtruicture tiMarkets<br />

years of regulation, has introduced a number of<br />

Although infrastructure markets with nurnerous major deregulatory initiatives over the past two<br />

suppliers are rare, competition among a few rival decades. In virtually all sectors, greater competition<br />

providers can lower costs and prices. The thieory has led to. lower prices or better services for conof<br />

contestable markets says thtat even where suiners-while efficiency gains and new technoloeconomnies<br />

of scale and scope favor a single gies or business practices have led to sustained profprovider,<br />

the existence of potential rival suppliers itability (Box 3.2).<br />

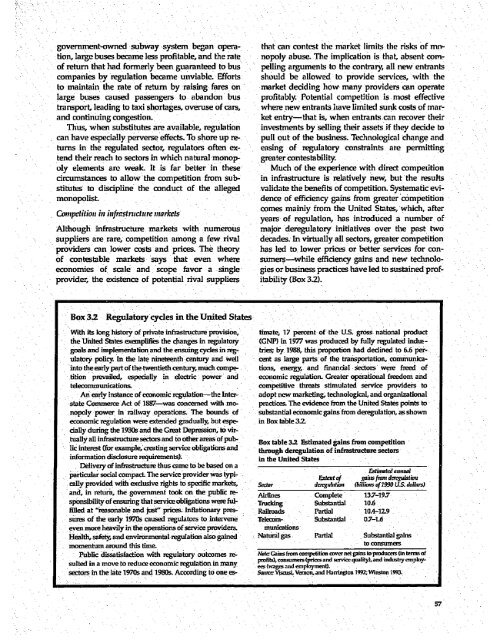

Box 32<br />

Regulatory cycles in the United States<br />

With its long history of private infrastrcture provision, timate, 17 percent of the U.S. gross national product<br />

the United States exemplifies the changes in regulatory (GNP) in 1977 was produced by fully regulated indugoals<br />

and implementalion and the ensuing cycles in reg- tries; by 1988, this proportion had declined to 6.6 perulatory<br />

poliy. In the late nineteenth century and well cent as large parts of the transportation, communicainto<br />

the early part of the twentieth centur, much compe- tions, energy, and financal sectors were freed of<br />

tition prevailed, especially in electric power and economic regulationL Greater operational freedom and<br />

teleconnmunications. - competitive threats stimulated service providers to<br />

An early instance of economic regulation-the Inter- adopt new marketing, technological, and organizational<br />

state Commnerce Act of 1887-was concerned with mo- practices. The evidence from the United States points to<br />

nopoly power in railway operations. The bounds of substantial economicgains from deregulation, as shown<br />

economic regulation were extended gradually, btut espe- in Box table 32-<br />

cialy during the 1930s and the Great Depression, to virtually<br />

all infrastructure sectors and to other areas of pub- Box table 32 Estited gains from competition<br />

lic interest (for example, creating service obligations and through deregulation of infrastructur sectors<br />

information disdosure requirements). - - the United Sttes<br />

Delivery of infrastructure thus came to be based on a<br />

Fslimotdal niame<br />

particular social compact The service provider was typi- ExStof ga fiun dutio<br />

cally provided with exdlusive rights to specific markets, -Seo dgnuFalion (billions of 1990 U.S. dollars)<br />

and, in return, the government took on the public re- Airlines Complete 13.7-19.7<br />

sponsibility of ensunng that service obligations were ful- Tmrcing, Substantial 10.6<br />

filled at easonable and just" prices. Inflationary pres- Railroads Partial 10.4-12.9<br />

sures of the early 1970s caused regulators to intervene Telecom- Substantial 0i7-1.6<br />

even more heavily in the operations of service providers. munications<br />

Health, safety, and enviromnental regulation also gained Natural gas Partial Substantial gains<br />

momentum around this time<br />

to consumers<br />

Public dissatisfaction with regulatory outcomes re- NetlcGains troi compefition cover netguinstoproducess(in teris of<br />

profits), consumers (pdiCCS and service quality), and industbv emnploysuited<br />

a move to reduce economic regulation in many ees(wagesandemployment).<br />

sectors in the late 1970s and 1980s. According to one es- Suture Viscsi, VerneRand Harrington 1992; Winston 1993.<br />

57