ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

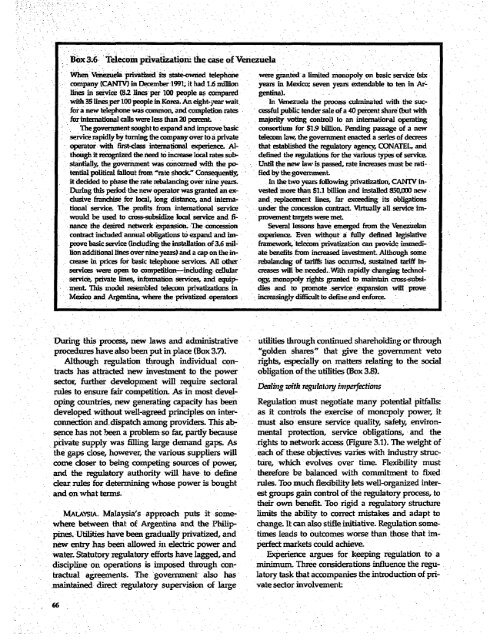

Box 3.6 Telecom piivatizati6ci the case of Venezuela<br />

When Venezuela privati2ed its stte-owned telephone were granted a limited monopoly on basic service (six<br />

company (CANTV) in DEcember 1991; it had 1.6 nMlion years in Mexico; seven veers extendable to ten in Arlilies<br />

in service (82 lines per 100 people as compared gentina).<br />

with 35 lines per 100 people inKorea. An eight-year wait In Venezuela the process culminated with the sucfora<br />

new telephone was common, and completion rates cessful public tender sale of a 40 percent share (but with<br />

for international calls were less than 20 perent<br />

majority voting control) to an internatioral operating<br />

The government sought to expand and improve basic consortium for $1.9 billionL Pending passage of a new<br />

service rapidly by tuni-ng the company over to i private telecom law, the government enacted a series of decrees<br />

operator- with first-class international experience. Al- that established the mrgulatory agency, CONATEL, and<br />

though it recognized the need to increase local rates sub- defined the regulations for the various types of service.<br />

stantially, the goverinment was concerned with the po- Until the new law is passed, rate increases must be ratitential<br />

political fallout from 4 rate shock:" Consequently, fled by the govemment<br />

it decided to phase the rate rebalandng over nine years. In the two years following privatization, CANTV in-<br />

During this period the newv operator was granted an ex- vested more than $1.1 billion and installed 850,000 new<br />

dusive franichise for local, long distance, and interna- and. replacement lines, far exceeding its obligations<br />

tional service The profits from international service under the concession contract. Virtually all service imwould<br />

be used to cross-subsidize lcal service and fi- provement targets were meL<br />

nance the desired network expansion. The concession Several Iessons have emnerged from the Venezuelan<br />

contract included annual obligations to expand and im- experienmc Even without a fully defined legislative<br />

prove basic service (induding the insallation of 3.6 mil- framework, telecom privatization can provide immedilion<br />

additional lines over nine years) and a cap on the in- ate benefits f orn increased investment Although some<br />

crease in prices for basic telephone services. All other rebalancing of tariff lias occmrd, sustained tariff inservices<br />

were open to competition-including celular creases will be needed. With rapidly changing techuolservice,<br />

private lines, information services, and equip- ogy, monopoly rights granted to maintain cross-subsimernt<br />

This model resembled telecom privatizations in dies and to promote service expansion will prove<br />

Mexico and Argentina, where the privatized operators increasingly difficult to define and enforce.|<br />

During this process, new laws and administrative utilities through continued shareholding or ftirough<br />

procedures have also been put in place (Box 3.7). "golden shares" that give the government veto<br />

Although regulation through individual con- rights, especially on matters reladng to the social<br />

tracts has attracted new investment to the power obligation of the utilities (Box 3.8).<br />

sector, further development will require sectoral<br />

rules to ensure fair competition. As in most devel- Dealing with regulalory hiperfections<br />

oping countries, new generating capacity has been Regulation must negotiate many potential pitfalls:<br />

developed without well-agreed principles on inter- as it controls the exercise of monopoly power, it<br />

connection and-dispatch among providers. This ab- must also ensure service quality, safety, environsence<br />

has not been a problem so far, partly because mental protection, service obligations, and the<br />

private supply was filling large demand gaps. As rnghts to network access (Figure 3.1). The weight of<br />

the gaps close, however, the various suppliers will each of these objectives varies with industry struccome<br />

doser to being competing sources of power, ture, which evolves over time. Flexibility must<br />

and the regulatory authority wfll have to define therefore be balanced with commitment to fixed<br />

clear rules for determining whose power is bought rules. Too much flexibility lets well-organized interand<br />

on what terms-<br />

est groups gain control of the regulatory process, to<br />

their own benefit Too rigid a regulatory structure<br />

MALAYSIA. Malaysia's approach puts it some- limits the ability to correct mistakes and adapt to<br />

where between that of Argentina and the Philip- change. It can also stifle initiative. Regulation sonepines.<br />

Utilities have been gradually privatized, and times leads to outcomes worse than those that imnew<br />

entry has been allowed in electric power and perfect markets could achieve.<br />

waten Statutory regulatory efforts have lagged, and Experience argues for keeping regulation to a<br />

discipline on operations is imposed through con- miriimum. Three considerations influence the regutractual<br />

agreements. The government also has latory. task that accompanies the introduction ofprimaintained<br />

direct regulatory supervision of large vate sector involvement<br />

66