ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

ASi" kUCTURE FlOR DEVELOPMENT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

pie of Latin American water utilties, collection of UNRSMPON5IVENIISS TO USIIR DEMAND. The result of<br />

* ~~~accounts receivable took almost four months on av- ineffidency anid poor.maintenance is Ioiw-quality,<br />

erage, compared with good-practice standards of unreliable service, whiuch alienates users. Reliability<br />

four to six weeks. In addition to creating an added is a critical aspect of user satisfaction that is often igburden<br />

on taxpayers, poor financial perfonnance by nored. Even where users have telephones, high call<br />

* nin~mny infrastructure provider-s means a loss of failure rates (more than 50 percent in many cases)<br />

credi'worthiness for the entity concerned. It also and high fault rates drastically diminish the value of<br />

results in a low reliance on internal revenues to. if. the service. Unreliable quantity or quality of water<br />

nance investment-and therefore an inability (antd leads to enormous i-nvestments in alterna tive sources<br />

lack of incentive) to expand or imnprove service. that are espeially costly to those who can least af-<br />

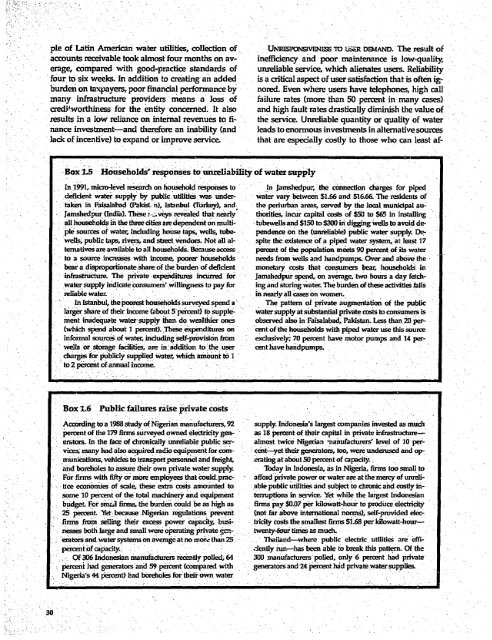

Box LS Households' responses to untreliability of water supply<br />

In 1991, micro-level research on household responses to Ini Jamshedpur, the c'onnection charges far piped<br />

deficient water supply by public.utilities was under- water vary between 51.66 and S16.6& The residents Of<br />

takenr in Faisalabad (Pakist. ni), Istanbul (rturkey), and the periurban areas, served by the local mutnicipal au-'<br />

Jamnshedpur (Endia). Theser cveys revealed that nearly thouities, incutr capital costs of 550 to 565 in installing<br />

ani ouseholds in the thee cities are dependent on multi- tubewells and $150 to $300 in digging wells to avoid depie<br />

sources of Watei, including ho-use taps, wells, tube- pendence on the (unreliable) public water supply. Diewells,<br />

public taps, rivers, and stzeet vendors. Not all al- spite the existence of a piped water systemi, at least 17<br />

ternatives are available to all households. Because access percent of the population meets 90 percent.of its wateri<br />

to a source increases with income, poorer households needs from. wells and handpup Over andl above the<br />

bear a disproportionate share of the burden of deficient monetary costs that consumers bear, households in<br />

'~~~~~ infrastruicture The priv'ate expeiiditures incurred for<br />

wrater supply indicate consumners' willinnesto pay for<br />

Jamshedpur spend, on a average, two hours- a day fetch-<br />

iri adstorin wtrThe b'urden of these activities fulls<br />

reliable water<br />

in nearly ail cases on women.<br />

In Istanbul, the poorest househblds surveyed spend a' The pattern of private augmentation of the public<br />

larger share of their income (abovut 5 -percent) to supple- water supply at s'ubstantial private costs to consumers zs<br />

ment iniadequate water supply than. do wealthier ones observed also in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Less than 20 er<br />

(which spend about 1 percent). Thh ese expenditures on' cent of the households with piped water use this source<br />

informal sources- of water, includintg self-provision fromi exdlusivelr; 70 percent have motor pumps and 14 perweli<br />

orstorge aciitie, ae i:addition to the user centhave handpumnps.<br />

chagesforpubicl suplid wter, which amount t6 I<br />

Box 1..6 Public failures raise private costs<br />

A~ccording to a 1988 study of Nigerian manufacturers, 92 supply. Indonesia's largest companies invested as much<br />

percent of the 179 ffirm surveyed owned electricity gen- as 18 percent of their capital in private infrastructureerators.<br />

In the face of chronically unreliable public ser- almost twice Nigerian -najiufactureise level of 10 pervices,<br />

many had also acquired radio equipment for corn- cent-yet their generators, too, were underused and opr<br />

munications, vehides to transport personnel and freight, era ting at abdut50 percent of capacity.:<br />

and boreholes to assure their o-wn p-rivate, water supply. Today in Indonesia, as in Nigeria, firms too small to<br />

Far firmnswith fiftycor mor emplcdyees that could prac- affordi private power or water are at the mercy of unrelitice<br />

econoibiues of scale, these extra costs amounted to. able public utilities and subject to chronic ajid costlyin<br />

some 10 percent of the total machinery and equipment terruptions in servic Yet while the largest hIndonesian<br />

budget. For sm&il finns, the burden could be as high as ffirms pay SO-07 pe!r koioatt-hour to produce electricity<br />

25 percenti Yet. because Nigeriain regulations prevent (not far above interntional normis), self-provided elecfrnms<br />

fromn selling their excess power capacity, busi- tricity costs the smallest firms $1.68 per kilowatt-hournesses<br />

both large and small were operating private c=- twenty-four timres as much.<br />

esators and.w-ater systemsron averageatno more than25<br />

perceni of cap-acity. * *<br />

*Thailand-where public electric utilities are fi<br />

iently rnm-has been able to) break.this pattern. Of the<br />

Of 306 Indonesian manufacturers recently polled, 64 3o 0 manufacturers poled, only 6 percent had private<br />

percent had generators'and 59 percent (compared with * generatorsand4 percent hid privatewatersupplies.<br />

Nigeria's 44 pewrent) had boreholes lbr theer own water<br />

.<br />

30