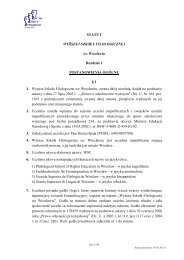

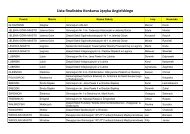

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

98<br />

Michael Hornsby<br />

[3]<br />

Will: “Thank you. That was perfect timing.”<br />

Grace: “I don’t have to be doing this.”<br />

Will: “Oh really? Really, <strong>we</strong>ll, you know, I didn’t have to spend Labor Day with your aunt<br />

Marsha in Boca Ratón, not that I didn’t love the yarn fayre. But I could have done without<br />

half the the condo complex pointing at me and whispering, ‘So that’s the faygeleh’.”<br />

“Faygele”<br />

The use of the Yiddish word for a gay man (faygele, lit. ‘little bird’), said in<br />

an exaggerated ‘Jewish’ accent can be used by one New Yorker to another with<br />

no offence intended or taken (depending on the context, obviously) because the<br />

use of Yiddish crosses ethnic lines, in very much the same way described by<br />

Carmen Fought (2006: 197) as “language crossing”, i.e., using a speech variety<br />

associated with a group other than the one you belong to.<br />

Particularly from a po<strong>we</strong>r differential perspective, the use of a term in a language<br />

that traditionally was not vie<strong>we</strong>d prestigiously to denote a member of<br />

society who was also not vie<strong>we</strong>d prestigiously (i.e., a faygele, or gay man)<br />

denotes, I would suggest, an attempt at solidarity bet<strong>we</strong>en two (formerly) oppressed<br />

groups: the Jews and the gay community. It is used here, obviously, for<br />

comic effect, but a very different effect might be imagined should the term have<br />

been used directly toward the character in question by a Yiddish speaker.<br />

Again, context is all.<br />

3.4. Who stands to gain or lose?<br />

The extracts, from [1] to [3], though brief, reveal much about the use of<br />

Yiddish for comic effect, particularly from a po<strong>we</strong>r differential viewpoint, as<br />

pointed out in 3b. When ans<strong>we</strong>ring the critical sociolinguistic question who<br />

stands to gain or lose, <strong>we</strong> can see that using Yiddish in such a way is not haphazard<br />

– a deliberate effect is aimed at. These include the continuation of a historical<br />

tradition of Jewish/Yiddish comedy or, as Neal Karlen reveals, the inheritance<br />

of “old-world Yiddish badchen, the funniest wise men of the shetl”<br />

(2008: 286). Ho<strong>we</strong>ver, this tradition has not been pursued solely in Jewish circles<br />

in America, and gains also include a greater inclusivity – the use of Yiddish<br />

by and for the entertainment of non-Jews in particular recalls one comedian’s<br />

statement that humour is universal. What is more, Karlen 2008: 287) cites one<br />

of the Jewish comic saying: “We [Jewish comics in America] expand it to include<br />

the whole society”. From a specific linguistic point of view, the use of<br />

Yiddish does not impede the flow of the comic routine or script but in fact adds<br />

to it, even though the vast majority of audience members and vie<strong>we</strong>rs are in fact<br />

non-Yiddish speakers. As Shandler (2006: 141) points out, it draws audiences<br />

together, particularly “at the symbolic level, invoking an erstwhile shared ethnic