s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

52<br />

Gabriela Brozbă<br />

The data provided by Mesthrie (2005) show that some features are indeed<br />

prevalent in the speech of speakers depending on their level of proficiency<br />

and/or second language acquisition, but they are not exclusive and should not be<br />

treated as ultimate diagnostic features of one speaker or another across the lectal<br />

continuum.<br />

Leaving aside the cline of proficiency for a moment, a few more observations<br />

on the distinction in terms of quality and quantity regarding the BSAE<br />

monophthong system are still in order. Daan Wissing (2002) carried out a perception<br />

study on the vo<strong>we</strong>l system of BSAE.<br />

The readings <strong>we</strong>re performed by three speakers: one having as L1 English,<br />

one of them Zulu, and the other one Southern Sotho. The listeners included 21<br />

Zulu L1 speakers, 21 Southern Sotho L1 speakers, 41 Arabic L1 speakers and<br />

20 Afrikaans L1 speakers. I will focus here only on the results for Bantu L1-<br />

speaking listeners. The significant results regarding vo<strong>we</strong>l length and vo<strong>we</strong>l<br />

quality are expressed in percentages in the table below:<br />

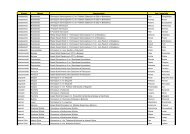

Table 3. Perception results of vo<strong>we</strong>l length and quality (adapted from Wissing 2002: 134,<br />

whereas only relevant results have been included)<br />

Reader(s) Correct responses Total possible cases<br />

English<br />

Length: 64% (293) Length: 460<br />

Quality: 49% (159) Quality: 326<br />

Bantu<br />

Length: 57% (553) Length: 976<br />

Quality: 43% (226) Quality: 522<br />

Total 2284<br />

The results in Table 3 point to at least two things: the speakers have greater<br />

difficulty in dealing with and distinguishing bet<strong>we</strong>en vo<strong>we</strong>l quality than bet<strong>we</strong>en<br />

vo<strong>we</strong>l length, and, secondly, the reading performance of a native speaker<br />

does not seem to improve significantly the recognition rate of the correct target<br />

words (i.e., only by 7% in terms of vo<strong>we</strong>l length and by 6% in terms of vo<strong>we</strong>l<br />

quality). The second assumption indicates that the vo<strong>we</strong>l system of Bantu L1<br />

speakers of BSAE is deeply rooted so that even when exposed to a native model<br />

they map it onto their own in most of the cases.<br />

I will take a closer look at vo<strong>we</strong>l quality in what follows by analyzing the<br />

results of the substitution patterns for the read words. The results for the Zulu<br />

and Southern Sotho listeners are summarized in Table 4.<br />

The substitutes actually represent the erroneously identified words for the<br />

word which are listed in the first column. I will conventionally assume that the<br />

words read by the speakers illustrate the expected renditions of the DRESS and<br />

TRAP vo<strong>we</strong>ls. First of all, it is worth mentioning that bird and turn are absent as<br />

input words, which, in light of the aforementioned convention, would translate<br />

in the absence of the NURSE vo<strong>we</strong>l from the vocalic system of the Bantu speakers.