s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

138<br />

Rhidian Jones<br />

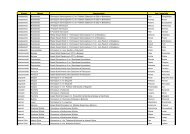

and that retreat continues today. Below are two maps of Wales based on the<br />

Census results of 1991 and 2001. In the dark-colored areas over 70% of inhabitants<br />

<strong>we</strong>re noted as Welsh-speaking and the decline in the size and number of<br />

these communities over the 10 years is evident. The communities where Welsh<br />

is the natural medium of daily life, in the north and <strong>we</strong>st of Wales, are being<br />

eroded, and the 2011 Census is likely to report the disappearance of any areas in<br />

the south that are more than 70% Welsh-speaking.<br />

There are various reasons for this process. We live in a mobile world and<br />

many young Welsh speakers leave their native areas to study or to find work.<br />

Wales’s Gross Domestic Product is lo<strong>we</strong>r than in other parts of the UK, and in<br />

south and <strong>we</strong>st Wales it is 71% of the UK average (BBC News, 25 February<br />

2011). Such an economic situation does not help in arresting the brain-drain out<br />

of the Welsh-speaking heartlands, and a statistician for the Welsh Language<br />

Board has estimated that there are 110 thousand Welsh speakers in England<br />

alone (Jones 2007: 10).<br />

An equally significant factor is in-migration, especially from England. The<br />

Welsh-speaking communities have stayed Welsh-speaking largely because of<br />

their isolation, and that isolation is now what is drawing people in – green hills,<br />

relatively cheap property, and a low crime rate. For each year bet<strong>we</strong>en 1981 and<br />

2005 Wales experienced a net inflow of migrants from the rest of the UK (National<br />

Statistics report 2006: 40) and this was particularly pronounced in areas<br />

such as Ceredigion and Conwy that have traditionally been strongholds of<br />

Welsh. These in-migrants <strong>we</strong>re mainly from older age brackets, while those<br />

who left Wales tended to be younger.<br />

There is no necessity or compulsion for incomers to learn Welsh since the<br />

bilingual nature of the area means they can use English only. Thus, the English<br />

language invades domains where Welsh was the main language, for example in<br />

the yard of the local school or in the pub, and poses a grave threat to the future<br />

of Welsh locally.<br />

Professors John Aitchison and Harold Carter (1994) encapsulated the effects<br />

of immigration on the Welsh heartlands in their study of the geography of<br />

the language:<br />

Cultural and linguistic continuity clearly depends on the relation bet<strong>we</strong>en the strength of the<br />

host population and numbers of incomers. There is a level where immigrants can be<br />

integrated, and indeed fall under pressure to integrate, and where they can add vitality to a<br />

community. But there is also a level where, because of the relatively high numbers,<br />

absorption does not take place, nor is it seen as necessary. There is a ‘tipping point’ where<br />

the domains of language use become restricted, the supporting cultural environment becomes<br />

attenuated and Anglicization intensifies (Aitchison and Carter 1994: 77–78).