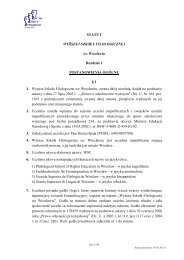

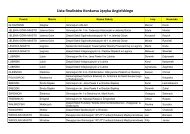

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

124<br />

Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup<br />

When constructing EU terminology in a new language one should remember<br />

that, it must stand in congruence with the already existing terminology,<br />

which means that EU terminology can neither exclude/contradict the target<br />

tongue terminology, nor replace it. When translating it is necessary to check<br />

whether a certain term exists in a target language or whether it was/is used in<br />

another legal system. All this aims at avoiding terminological collision. It boils<br />

down to the premise that a translator cannot show ignorance to the historically<br />

determined phraseology of the target language (Kierzkowska 2002). A translator<br />

should also be equipped with the knowledge of the legal system of one’s<br />

own country and the legal system of the country whose legislation is under<br />

translation, in simplest terms the knowledge of civil and common law culture.<br />

The real craft of the legal translation is, according to Jerzy Pieńkoś (2003), the<br />

ability to compare legal systems, which pertains to the comparative law knowledge.<br />

Nevertheless, in reference to the EU it is no longer certain whether one<br />

should talk about one legal system or maybe separate legal systems of Member<br />

States; two opposite standpoints in legal theory dominate, namely the view that<br />

EU law comprises distinct and coexistent legal systems and the view that there<br />

exists a single legal system (Viola 2007: 106–108).<br />

One of the priorities of multilingual translation is a concordance of parallel<br />

versions of one treaty. The disregard for congruence can spark problems with<br />

the application of the law provisions. Two notions are put forward such as concordance<br />

and harmonization. As stated above, concordance refers to all language<br />

versions and harmonization means that a terminology used in one text<br />

should be consistent within run-on sentences. Of course, absolute symmetry is<br />

not possible to achieve. The challenge of translating EU treaties is how to preserve<br />

the intended meaning congruent in all language versions together with the<br />

purity of one’s language. As Susan Šarcevic (2000) ascertains, the task becomes<br />

even more difficult with each new language added to the family of EU languages.<br />

From a translator’s point of view, it is important to mention the division<br />

of a treaty into restricted and non-restricted parts. The restricted parts contain<br />

technical vocabulary, whilst non-restricted or free ones do not deviate from the<br />

ordinary discourse. A certain creativity is allo<strong>we</strong>d only in the non-restricted part<br />

(Šarcevic 2000: 224–226).<br />

5. The analysis of sample translations<br />

In the following section, the notion of language contact in the EU context is<br />

elaborated on in detail. Some examples taken from the treaty on European Union<br />

and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union will serve as an<br />

illustration. The goal of the study is not to evaluate translator’s skills but rather<br />

to exhibit what the manifestations of language contact are, particularly how