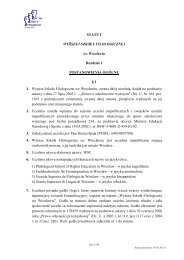

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

94<br />

Michael Hornsby<br />

many baley-tshuves [returnees to Judaism] who do not know it” (Fader 2009:<br />

11). Another point made by other commentators centres on the fact that Yiddish,<br />

like many other endangered languages, is in contact situation with a much<br />

more po<strong>we</strong>rful and prestigious language in the United States (and elsewhere)<br />

and this can lead to mixed linguistic practices, particularly among male speakers<br />

who attend yeshivas (schools of advanced Jewish study), further diminishing<br />

its use as a vernacular: “A new dialect of English sometimes called Yeshivish is<br />

taking over as the vernacular in everyday life in some [ultra-orthodox] circles in<br />

America and elsewhere” (Katz 2004: 384).<br />

The second response to this situation of endangerment is to claim that Yiddish<br />

is very much “alive” (cf. the Polish-based cultural movement “Yidish<br />

Lebt” (jidysz.net) who proclaim in their very title the (imagined) vitality of the<br />

language, “imagined” in a Polish context since there is no significant body of<br />

speakers of the language left anywhere in Poland).<br />

Commentators such as Katz see the future of Yiddish as secure in particular<br />

settings: “Yiddish, as fate would have it, is 100 percent safe for centuries to<br />

come as a virile spoken and written language among the southern Hasidim …<br />

The vast majority speak … Póylish … And this is the majority Yiddish of the<br />

future” (Katz 2004: 385). And indeed, the language, according to this discourse,<br />

will actually increase its demographic base of speakers: “The future millions of<br />

Yiddish speakers … will come from the rapidly expanding Hasidic communities<br />

around the world … while the next major chapter in the unfinished history<br />

of Yiddish is created by the Hasidim, <strong>we</strong> [secularists] can muster the collective<br />

energy needed for efforts to write our own much smaller chapter” (Katz 2004:<br />

397–398). If the attested 5% annual increase among the Hasidim results in the<br />

doubling of the Hasidic population every 15 years, then there will be, according<br />

to Robert Eisenberg (1995) 10 million Yiddish speakers by 2075.<br />

Assuming that Yiddish is in the state of a “dying” language, it is also a language<br />

which is subjected to predictions of imminent “death”. Ho<strong>we</strong>ver, predictions<br />

do not always come true and do not always reflect the current situation of<br />

a language. They can ho<strong>we</strong>ver influence current attitudes towards a language<br />

and end up causing speakers to question the validity of continuing to transmit or<br />

even speak the language in question. In other words, these attitudes can create<br />

a self-fulfilling prophecy. In this context, Jefrrey Shandler (2006: 177–178) lists<br />

a discourse of language “death” in relation to Yiddish, which has been underway<br />

for over a century now and yet Yiddish as a spoken language is still with<br />

us:<br />

1897: “Within t<strong>we</strong>nty-five years … even the best works in this language will only be literary<br />

curiosities” (Rosenfeld).<br />

1899: “In America [Yiddish] is certainly doomed to extinction” (Wiener).