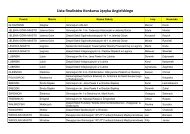

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

204<br />

Agnieszka Stępkowska<br />

more and more spheres of life, and the Romansh dialects put up resistance,<br />

though rather <strong>we</strong>ak in the final analysis.<br />

When <strong>we</strong> move further on the Haugen’s cycle, <strong>we</strong> arrive at what Uriel<br />

Weinreich (1968 /1953/: 1) described as “the practice of alternately using two<br />

languages”, i.e.,, bilingualism. If prolonged, bilingualism may result in shift.<br />

Haugen (1972) distinguishes bet<strong>we</strong>en supplementary, complementary, and replacive<br />

bilingualism. These three kinds of bilingualism may occur together or<br />

separately in any social context. They may ensue in a chronological order,<br />

marked by the gradual change of the generations, like in the Romansh case.<br />

Their communicative needs cannot be fulfilled entirely by any of the Romansh<br />

dialects and, in consequence, they need to learn German. Thus, they may learn<br />

it as a supplement to Romansh for specific needs. Or, they may wish to learn to<br />

read and write Standard German, which thereby fulfills a complementary function<br />

to the first language. Or, in the replacive bilingualism, German may gradually<br />

take over all the communicative needs of the speakers so that the use of<br />

Romansh is rendered useless and, in the end, consigned to oblivion.<br />

If bilingualism is not secured at a steady level, then the process of shift ensues.<br />

The first symptoms are indicated by fe<strong>we</strong>r users and a diminishing political<br />

status. If the replaced language begins to lose economic attractiveness and<br />

its knowledge is no longer demanded in pursuing professional career, as <strong>we</strong>ll as<br />

if its social prestige starts to shrink, then that language should be regarded as<br />

seriously threatened. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas (2003: 33) deplores the situations<br />

of shifts, arguing that “big languages turn into killer languages, monsters that<br />

gobble up others, when they are learned at the cost of the smaller ones. Instead,<br />

they should and could be learned in addition to the various mother tongues”.<br />

Thus, the shift is complete when the replaced language has disappeared completely<br />

– a state also referred to as language loss or, to use a more elaborate<br />

term, glottophagia, i.e., “the suppression of the minority language by that of the<br />

majority” (Calvet 1974, in Nelde 1992: 391). The shift bet<strong>we</strong>en languages reflects<br />

the proportions or balance of po<strong>we</strong>rs, which means that the demise of<br />

a language is always brought about by non-linguistic causes (Maurais 2003:<br />

28). When a language dies, no single native speaker of it is left and “all its functions<br />

or uses have been usurped by another language” (Pau<strong>we</strong>ls 2004: 719).<br />

Thus language contact, being the prerequisite of language shift as <strong>we</strong>ll as its<br />

first potential stage, may (though it does not have to) involve linguistic competition.<br />

3. Researching language shift<br />

For several decades the study of the erosion of Romansh grew multidisciplinary<br />

in nature, and this fact is reflected in the multitude of research method