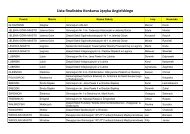

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Language shift in the Raeto-Romansh community 207<br />

guage. Virtually all speakers of Romansh can speak either two or more languages,<br />

which makes them – beside their Italian-speaking compatriots – truly<br />

multilingual individuals. Thus, their attitude to bilingualism needs to combine<br />

“an emotional attachment to Romansh and a rational commitment to German”<br />

(Stevenson 1990: 252).<br />

Most of the major reasons for the decline of Romansh <strong>we</strong>re already listed<br />

some thirty years ago by McRae (1983) in his Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual<br />

Societies: Switzerland. It appears that most of those reasons are still<br />

relevant today, which means that they have not been eliminated, and the countermeasures<br />

aiming to strengthen the position of Romansh in the meantime have<br />

turned out to be less than effective. Kenneth McRae (1983) compiled a long list<br />

of problems directly affecting the Romansh minority in Switzerland. These<br />

problems include: the waning proportion of Romansh speakers resulting from<br />

inter-cantonal migration; the mixing of population in the canton; the lack of any<br />

major Romansh-speaking municipality; no recognition of the Romansh region<br />

in either cantonal or federal law; the utmost dialectal variation (discussed in the<br />

following section of the article); an equal divide of the total population of the<br />

Grisons in religion bet<strong>we</strong>en Protestants and Roman Catholics. All these problems<br />

surely are not counteracted with sufficient determination by institutional<br />

controls. At present, Liga Romontscha, an organized interest group, seems to be<br />

the last mainstay of the Romansh languages. Unfortunately, its frequently successful<br />

activities are neither reflected in authoritative decision-making, nor<br />

forged into any legal enforcement.<br />

In the discussions about the mechanisms of language change, the issue of<br />

speakers’ attitudes is often raised. Perhaps those who most deplore the vanishing<br />

minority languages are not the ones using them in everyday life, like linguists<br />

or intellectual elites. It leaves no room for illusion that today Romansh is<br />

associated by its native speakers with the language of the elderly and the traditional,<br />

agrarian or pastoral culture, whereas modern technological vocabulary is<br />

sought in German. In his study, Weinreich (1968 /1953/) proved that Romansh<br />

ranked low in social prestige and German was to secure educational, professional<br />

and economic advancement. McRae (1983) writes about a “substantial<br />

attitudinal gap” bet<strong>we</strong>en the Raetoroman intellectual elite and the average citizen,<br />

which leads us to conclude that the survival of Romansh has remained primarily<br />

an elite concern. The future of Romansh is very much dependent on the<br />

commitment of Romansh speakers themselves, for it is difficult to cultivate<br />

a minority language, when this minority itself decides on a majority language<br />

for practical reasons. The absence of these pragmatic reasons for language<br />

maintenance puts the language in jeopardy, thereby implying an indissoluble<br />

relationship bet<strong>we</strong>en language and economics (see also Grin 1990).