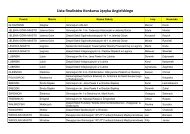

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

s - Wyższa SzkoÅa Filologiczna we WrocÅawiu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

208<br />

Agnieszka Stępkowska<br />

By way of recap, it seems purposeful to recall some generalized points<br />

made by Edwards (1985) whose surveys, in fact, converged to form a list of<br />

universal observations readily applicable to any minority language struggling<br />

for survival. These points are also true of Romansh. That is to say, all languages<br />

on the decline are mostly spoken by an older generation and are not transmitted<br />

further on to younger people; languages undergoing shifts are often cramped<br />

into poor and rural areas; bilingualism is only of transitory nature; the most<br />

explicit desire for language maintenance is voiced by small unrepresentative<br />

groups; and, finally, a group identity usually survives language death. All in all,<br />

reversing language shift is highly unlikely in practice if not completely impossible.<br />

Usually, efforts to revive a dying language prove to be artificial, or “removed<br />

from a realistic overall appreciation of social dynamics” (Edwards 1985:<br />

169), and therefore doomed to failure. Language decline needs to be researched<br />

and understood in a wide social context “with full appreciation of the processes<br />

of social evolution which have created contemporary conditions” (Edwards<br />

1985: 169). If these conditions are natural and normal in every way, then the<br />

final consequence they lead to should also be regarded as such. And, this is<br />

what May (2004) calls the “resigned language realism”.<br />

5. Rumantsh Grischun – one instead of five<br />

Under the territorial principle all language groups are relatively stable and easy<br />

to define. Georges Lüdi (1992: 46) elaborates on this description as follows:<br />

The validity of the territoriality principle in Switzerland changed its administrative map into<br />

a patchwork of monolingual cantons with the exception of a few overlap areas in case of<br />

a couple of officially bilingual cantons. Depending on the viewpoint, the territoriality<br />

principle either constrains or permits the use of one official language. As a result, the other<br />

national languages in any given monolingual canton enjoy the status comparable to that of<br />

Spanish or English.<br />

The situation of Romansh communities has remained unsolved, and it will<br />

remain as such, unless the numbers in statistics concerning Romansh come to<br />

a halt. In the opinion of Lüdi (1992), the territorial principle deals rather poorly<br />

with school problems and migration across the language borders. The formerly<br />

unforeseen abundance of language contacts, brought about by industrial and<br />

economic development and the po<strong>we</strong>r of the mass media, will not stop at the<br />

cantonal borders. According to Blommaert (2004: 59), “territorialization stands<br />

for the perception and attribution of values to language as a local phenomenon,<br />

something which ties people to local communities and spaces. Customarily,<br />

people’s mother tongue (L1) is perceived as territorialized language” (my emphasis).<br />

Nevertheless, for the dispersed Romansh communities the issues of