- Page 2 and 3:

Routledge History of Philosophy Vol

- Page 4 and 5:

Routledge History of Philosophy Vol

- Page 6 and 7:

v 1. Philosophy, Renaissance. 2. Ph

- Page 8 and 9:

vii Glossary 389 Index of names 407

- Page 10 and 11:

element in learning about the natur

- Page 12 and 13:

J.G.Cottingham is Professor of Phil

- Page 14 and 15:

xiii Politics and Religion The Arts

- Page 16 and 17:

xv Politics and Religion The Arts 1

- Page 18 and 19:

xvii Politics and Religion The Arts

- Page 20 and 21:

xix Politics and Religion The Arts

- Page 22 and 23:

xxi Politics and Religion The Arts

- Page 24 and 25:

xxiii Politics and Religion The Art

- Page 26 and 27:

xxv Politics and Religion The Arts

- Page 28 and 29:

xxvii Politics and Religion The Art

- Page 30 and 31:

2 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTU

- Page 32 and 33:

4 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTU

- Page 34 and 35:

6 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTU

- Page 36 and 37:

8 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTU

- Page 38 and 39:

10 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENT

- Page 40 and 41:

12 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENT

- Page 42 and 43:

14 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CENT

- Page 44 and 45:

16 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 46 and 47:

18 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 48 and 49:

20 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 50 and 51:

22 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 52 and 53:

24 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 54 and 55:

26 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 56 and 57:

28 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 58 and 59:

30 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 60 and 61:

32 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 62 and 63:

34 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 64 and 65:

36 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 66 and 67:

38 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 68 and 69:

40 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 70 and 71:

42 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 72 and 73:

44 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 74 and 75:

46 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 76 and 77:

48 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 78 and 79:

50 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 80 and 81:

52 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 82 and 83:

54 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 84 and 85:

56 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 86 and 87:

58 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 88 and 89:

60 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 90 and 91:

62 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 92 and 93:

64 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE ITALIAN RE

- Page 94 and 95:

66 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 96 and 97:

68 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 98 and 99:

70 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 100 and 101:

72 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 102 and 103:

74 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 104 and 105:

76 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 106 and 107:

78 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 108 and 109:

80 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 110 and 111:

82 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 112 and 113:

84 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 114 and 115:

86 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 116 and 117:

88 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 118 and 119:

90 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 120 and 121:

92 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 122 and 123:

94 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 124 and 125:

96 RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY OUTSIDE I

- Page 126 and 127:

98 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO DE

- Page 128 and 129:

100 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 130 and 131:

102 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 132 and 133:

104 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 134 and 135:

106 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 136 and 137:

108 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 138 and 139:

110 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 140 and 141:

112 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 142 and 143:

114 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 144 and 145:

116 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 146 and 147:

118 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 148 and 149:

120 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 150 and 151:

122 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 152 and 153:

124 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 154 and 155:

126 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 156 and 157:

128 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS UP TO D

- Page 158 and 159:

CHAPTER 4 Francis Bacon and man’s

- Page 160 and 161:

132 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 162 and 163:

134 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 164 and 165:

136 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 166 and 167:

138 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 168 and 169:

140 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 170 and 171:

142 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 172 and 173:

144 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 174 and 175:

146 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 176 and 177:

148 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 178 and 179:

150 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 180 and 181:

152 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 182 and 183:

154 FRANCIS BACON AND MAN’S TWO-F

- Page 184 and 185:

CHAPTER 5 Descartes: methodology St

- Page 186 and 187:

158 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 188 and 189:

160 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 190 and 191:

162 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 192 and 193:

164 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 194 and 195:

166 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 196 and 197:

168 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 198 and 199:

170 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 200 and 201:

172 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 202 and 203:

174 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 204 and 205:

176 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 206 and 207:

178 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 208 and 209:

180 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 210 and 211:

182 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 212 and 213:

184 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 214 and 215:

186 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 216 and 217:

188 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 218 and 219:

190 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 220 and 221:

192 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 222 and 223:

194 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 224 and 225:

196 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 226 and 227:

198 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 228 and 229:

200 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 230 and 231:

202 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 232 and 233:

204 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 234 and 235:

206 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 236 and 237:

208 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 238 and 239:

210 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 240 and 241:

212 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 242 and 243:

214 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 244 and 245:

216 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 246 and 247:

218 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 248 and 249:

220 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 250 and 251:

222 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 252 and 253:

224 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 254 and 255:

226 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 256 and 257:

228 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 258 and 259:

230 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 260 and 261:

232 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 262 and 263:

234 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 264 and 265:

236 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 266 and 267:

238 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 268 and 269:

240 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 270 and 271:

242 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 272 and 273:

244 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 274 and 275:

246 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 276 and 277: 248 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 278 and 279: 250 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 280 and 281: 252 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 282 and 283: 254 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 284 and 285: 256 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 286 and 287: 258 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 288 and 289: 260 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 290 and 291: 262 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 292 and 293: 264 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 294 and 295: 266 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 296 and 297: 268 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 298 and 299: 270 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 300 and 301: 272 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 302 and 303: 274 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 304 and 305: 276 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 306 and 307: 278 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 308 and 309: 280 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 310 and 311: 282 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 312 and 313: 284 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 314 and 315: 286 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

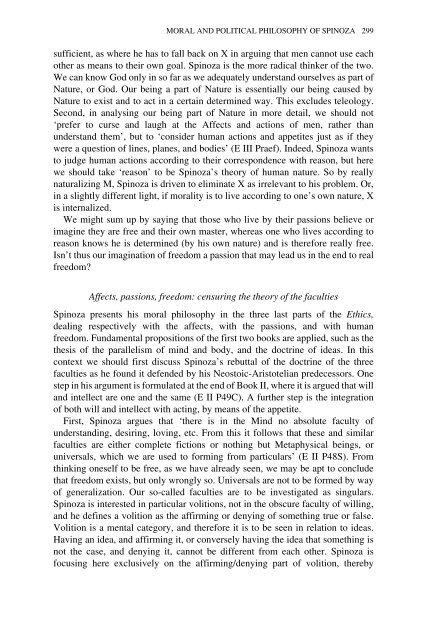

- Page 316 and 317: CHAPTER 9 The moral and political p

- Page 318 and 319: 290 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 320 and 321: 292 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 322 and 323: 294 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 324 and 325: 296 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 328 and 329: 300 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 330 and 331: 302 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 332 and 333: 304 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 334 and 335: 306 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 336 and 337: 308 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 338 and 339: 310 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 340 and 341: 312 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 342 and 343: 314 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 344 and 345: 316 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 346 and 347: 318 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 348 and 349: CHAPTER 10 Occasionalism Daisie Rad

- Page 350 and 351: 322 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 352 and 353: 324 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 354 and 355: 326 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 356 and 357: 328 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 358 and 359: 330 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 360 and 361: 332 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 362 and 363: 334 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 364 and 365: 336 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 366 and 367: 338 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 368 and 369: 340 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 370 and 371: 342 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 372 and 373: 344 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 374 and 375: 346 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 376 and 377:

348 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 378 and 379:

350 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 380 and 381:

352 RENAISSANCE AND SEVENTEENTH-CEN

- Page 382 and 383:

354 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 384 and 385:

356 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 386 and 387:

358 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 388 and 389:

360 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 390 and 391:

362 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 392 and 393:

364 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 394 and 395:

366 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 396 and 397:

368 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 398 and 399:

370 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 400 and 401:

372 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 402 and 403:

374 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 404 and 405:

376 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 406 and 407:

378 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 408 and 409:

380 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 410 and 411:

382 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 412 and 413:

384 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 414 and 415:

386 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 416 and 417:

388 LEIBNIZ: TRUTH, KNOWLEDGE AND M

- Page 418 and 419:

390 GLOSSARY attribute: Averroism:

- Page 420 and 421:

392 GLOSSARY compositio: a Latin ve

- Page 422 and 423:

394 GLOSSARY disposition: double as

- Page 424 and 425:

396 GLOSSARY gnoseology: habitus: H

- Page 426 and 427:

398 GLOSSARY induction, eliminative

- Page 428 and 429:

400 GLOSSARY modus tollens: monad:

- Page 430 and 431:

402 GLOSSARY Organon: pantheism: pa

- Page 432 and 433:

404 GLOSSARY Remonstrants: resoluti

- Page 434 and 435:

406 GLOSSARY truth, double: truth,

- Page 436 and 437:

408 INDEX OF NAMES Ceredi, Giuseppe

- Page 438 and 439:

410 INDEX OF NAMES Plato 6, 20, 29,

- Page 440 and 441:

412 INDEX OF SUBJECTS cogito ergo s

- Page 442 and 443:

414 INDEX OF SUBJECTS civil 264, 33

- Page 444:

416 INDEX OF SUBJECTS Descartes’

![Emile ou De l'ducation [Document lectronique] / Jean-Jacques ...](https://img.yumpu.com/51194314/1/190x245/emile-ou-de-lducation-document-lectronique-jean-jacques-.jpg?quality=85)