- Page 2 and 3:

THE BUCHAREST ACADEMY OF ECONOMIC S

- Page 4 and 5:

CONTENTS Preface PS1 Auditing Chair

- Page 6 and 7:

ENTERPRISE 2.0 - IS THE MARKET READ

- Page 8 and 9:

SEMANTIC ANNOTATION AND ASSOCIATION

- Page 10 and 11:

ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES AND BOOK-TAX

- Page 12 and 13:

EMPIRICAL STUDY REGARDING KEY INDIC

- Page 14 and 15:

She is the Accounting Department Ed

- Page 16 and 17:

AUDIT COMMITTEES AS INCREASING VECT

- Page 18 and 19:

took into account the essential rol

- Page 20 and 21:

independence, competence, professio

- Page 22 and 23:

shareholders as companies’ owners

- Page 24 and 25:

expertise which could control the m

- Page 26 and 27:

information asymmetry. According to

- Page 28 and 29:

indicators reducing audit quality),

- Page 30 and 31:

This study reflects my own opinion

- Page 32 and 33:

Malone, C.F. & Roberts, R.W. (1996)

- Page 34 and 35:

findings. As the audit process is a

- Page 36 and 37:

(Weber et al., 2002) present a psyc

- Page 38 and 39:

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The researc

- Page 40 and 41:

isk behaviour using the SPSS statis

- Page 42 and 43:

conclusion of this study, that age

- Page 44 and 45:

APPENDIX 1 The research questionnai

- Page 46 and 47:

THE INVESTIGATION OF ROMANIAN AUDIT

- Page 48 and 49:

1. ROLE AND PRACTICES OF INTERNAL A

- Page 50 and 51:

• Internal audit assist the board

- Page 52 and 53:

But there are only few papers that

- Page 54 and 55:

14. Internal audit should discussed

- Page 56 and 57:

have its place in the repertoire of

- Page 58 and 59:

11 Internal audit assists board/aud

- Page 60 and 61:

16 Internal audit is preoccupied by

- Page 62 and 63:

Chief of internal audit department

- Page 64 and 65:

Based on the above tables, we propo

- Page 66 and 67:

the answers and resending some foll

- Page 68 and 69:

Sarens G (2009) „Internal auditin

- Page 70 and 71:

PUBLIC SECTOR PERFORMANCE FROM THE

- Page 72 and 73:

integrating social responsibility i

- Page 74 and 75:

Administration, the Ministries, oth

- Page 76 and 77:

The research points out that there

- Page 78 and 79:

odies disclose information on the s

- Page 80 and 81:

On one hand, it helps them to build

- Page 82 and 83:

Steps Description Implement CSR com

- Page 84 and 85:

Gjølberg, M. (2009) „Measuring t

- Page 86 and 87:

ANNEX 1 Disclosures on social respo

- Page 88 and 89:

Country Name of Institution Finland

- Page 90 and 91:

Country Name of Institution The The

- Page 92 and 93:

IMPROVEMENT IN ACCOUNTING SYSTEM AN

- Page 94 and 95:

1.2. Improved accounting system (H1

- Page 96 and 97:

Shields and Shields (1998) have rev

- Page 98 and 99:

Flamholtz (1983) argues that accoun

- Page 100 and 101:

2. VARIABLE MEASUREMENT For variabl

- Page 102 and 103:

To analyse the data, Structural Equ

- Page 104 and 105:

eliable. Of all indices in Table 2

- Page 106 and 107:

e10 e9 e8 e7 e6 e5 e4 e3 e2 e1 Figu

- Page 108 and 109:

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION By lookin

- Page 110 and 111:

of SEM as the main data analysing p

- Page 112 and 113:

Cooper, R. (1995). When lean enterp

- Page 114 and 115:

Modell, S., Lee, A., Tjenesteproduk

- Page 116 and 117:

a centrally planned economy era and

- Page 118 and 119:

are used and respected by the major

- Page 120 and 121:

Financial control Figure 1. Managem

- Page 122 and 123:

Table 2. The evolution of the defin

- Page 124 and 125:

Poland, a different solution has be

- Page 126 and 127:

continuous quality improvement by s

- Page 128 and 129:

• has full legal capacity and mak

- Page 130 and 131:

and metrics to measure efficiency.

- Page 132 and 133:

Currently, internal audit is becomi

- Page 134 and 135:

BOUNDRIES REGARDING THE IMPLEMENTAT

- Page 136 and 137:

including the credit institutions a

- Page 138 and 139:

What are the coordinates of this na

- Page 140 and 141:

• improving the quality of inform

- Page 142 and 143:

the parent companies prepare the co

- Page 144 and 145:

statements and the audit report, it

- Page 146 and 147:

The Insurance Supervisory Commissio

- Page 148 and 149:

eform went ahead the economy reform

- Page 150 and 151:

PS3 Financial analysis I Chairperso

- Page 152 and 153:

to-unit root properties. Thus, ther

- Page 154 and 155:

we use the “Windmeijer correction

- Page 156 and 157:

2.2. Results Our preliminary evalua

- Page 158 and 159:

M1 and M2 are tests for first-order

- Page 160 and 161:

Goyal A., Welch I., (2003) „Predi

- Page 162 and 163:

' ∑ = LΛL ( a.4. ) Here L is the

- Page 164 and 165:

Among these categories, the first i

- Page 166 and 167:

Authors Main tested method Sample c

- Page 168 and 169:

pay more attention to accurately cl

- Page 170 and 171:

whose total assets were below 100K

- Page 172 and 173:

Step 6: An algorithm based on multi

- Page 174 and 175:

called knots, nodes or breakdown po

- Page 176 and 177:

RMSECV = n ∑ i= 1 ( y − yˆ ) i

- Page 178 and 179:

the whole database and performed fi

- Page 180 and 181:

Bank for International Settlements

- Page 182 and 183:

Martikainen, T., Perttunen, J., Yli

- Page 184 and 185:

THE RELEVANCE OF COMPANY EVALUATION

- Page 186 and 187:

qualitative data, present in the co

- Page 188 and 189:

Although financial theory criticize

- Page 190 and 191:

isk (one characterized by the insol

- Page 192 and 193:

Table 3. List of the companies in t

- Page 194 and 195:

each of the three variables: 1 - lo

- Page 196 and 197:

Table 4. Coefficients of the classi

- Page 198 and 199:

a total error for the case when thi

- Page 200 and 201:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supp

- Page 202 and 203:

FINANCIAL RISK ANALYSIS AT THE STOC

- Page 204 and 205:

society we live in. Additionally, r

- Page 206 and 207:

loans of the banking system, they m

- Page 208 and 209:

Graph 1. CLF evolutions during 2005

- Page 210 and 211:

The times we are living require the

- Page 212 and 213:

BENEFITS AND COSTS OF PREPARING IFR

- Page 214 and 215:

1.2. Paper’s aim and contribution

- Page 216 and 217:

� introduction of basic principle

- Page 218 and 219:

• the consistency of adjustments

- Page 220 and 221:

� all-in-one solution, when entit

- Page 222 and 223:

• Voluntary application of the IF

- Page 224 and 225:

other sophisticated systems are use

- Page 226 and 227:

Certainly Rather yes Rather not Cer

- Page 228 and 229:

classified as investments in associ

- Page 230 and 231:

PS5 Fair value Chairperson Mihaela

- Page 232 and 233:

1. BACKGROUND The main objective of

- Page 234 and 235:

transactions involving identical or

- Page 236 and 237:

and the representative body which t

- Page 238 and 239:

market data (see paragraphs 36 and

- Page 240 and 241:

The most advantageous market is the

- Page 242 and 243:

Question 10 With the sixth question

- Page 244 and 245:

proposed guidance does not sufficie

- Page 246 and 247:

% 100,00 80,00 60,00 40,00 20,00 0,

- Page 248 and 249:

the criticisms and suggestions, the

- Page 250 and 251:

AN ENTERPRISE ONTOLOGICAL APPROACH

- Page 252 and 253:

example, in this sense, constitutes

- Page 254 and 255:

• Setting properties for each cla

- Page 256 and 257:

3.5. Defining properties for classe

- Page 258 and 259:

McCarthy W.E. (1982), “The REA ac

- Page 260 and 261:

1. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY This attemp

- Page 262 and 263:

novelty, the difference resides in

- Page 264 and 265:

comes with unlimited scalability at

- Page 266 and 267:

the main reason to embrace Enterpri

- Page 268 and 269:

• A large multinational company p

- Page 270 and 271:

fluctuating demands, and cost savin

- Page 272 and 273:

development, taking advantage of th

- Page 274 and 275:

The adoption of the new software di

- Page 276 and 277:

NON-TECHNICAL CHALLENGES IN ADOPTIN

- Page 278 and 279:

• The virtualization techniques a

- Page 280 and 281:

identification of compliance reques

- Page 282 and 283:

overloaded. In such situations, ins

- Page 284 and 285:

alternative, able to significantly

- Page 286 and 287:

or reliability issues. As the cloud

- Page 288 and 289:

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR THE OR

- Page 290 and 291:

Data breaches is in the forefront o

- Page 292 and 293:

Enterprise Governance is a relative

- Page 294 and 295:

These four domains are interrelated

- Page 296 and 297:

3.2 Oracle database audit steps Thr

- Page 298 and 299:

• Export files The auditor should

- Page 300 and 301:

• Access and authorization All us

- Page 302 and 303:

REFERENCES Al Marcella (2006) IT Au

- Page 304 and 305:

USE OF FINANCIAL SECURITIES IN THE

- Page 306 and 307:

etween the listing of accounting un

- Page 308 and 309:

within the latter becomes possible

- Page 310 and 311:

Price/Earnings ratio model is a ver

- Page 312 and 313:

Bills of exchange and checks repres

- Page 314 and 315:

Pirchegger (2006) is concerned with

- Page 316 and 317:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper is one

- Page 318 and 319:

THE FINANCIAL INNOVATION AND THE DY

- Page 320 and 321:

The financial engineering represent

- Page 322 and 323: characteristics: form (capital mark

- Page 324 and 325: Compared with the ETFs, the options

- Page 326 and 327: Graph 1. The evolution of ETFs at g

- Page 328 and 329: 5.5 billion $, the most important f

- Page 330 and 331: Figure 1. Mainstream View of Global

- Page 332 and 333: seams to intensify the pessimism of

- Page 334 and 335: Marshall, J. & Bansal, V. (2004) Fi

- Page 336 and 337: selection had the strongest impact

- Page 338 and 339: n+ 1 m ∑ri X i + ∑R j z j = ∑

- Page 340 and 341: 2. FUZZY MIXED SECURITIES PORTFOLIO

- Page 342 and 343: Figure 4. The membership function f

- Page 344 and 345: We already have the values of f M a

- Page 346 and 347: CONCLUSIONS We can conclude by show

- Page 348 and 349: THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL DESCRIPTORS I

- Page 350 and 351: � Leverage (GI) - reflect the tot

- Page 352 and 353: each unit of risk. It is calculated

- Page 354 and 355: Analyzing these results shows that

- Page 356 and 357: In the short portfolios case only t

- Page 358 and 359: APPENDIX 1 Issuing companies from t

- Page 360 and 361: APPENDIX 3 Issuing companies from t

- Page 362 and 363: APPENDIX 5 Issuing companies from t

- Page 364 and 365: Issuers Reverse of the historical v

- Page 366 and 367: Issuers Reverse of the historical v

- Page 368 and 369: Issuers Reverse of the historical v

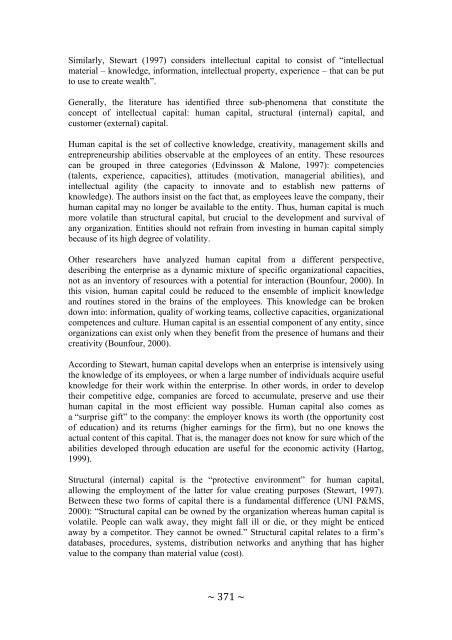

- Page 370 and 371: INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL DISCLOSURE: EU

- Page 374 and 375: In a manner similar to prior resear

- Page 376 and 377: information related to their intang

- Page 378 and 379: As shown in Figure 3, within extern

- Page 380 and 381: Bontis, N. (1998). “Intellectual

- Page 382 and 383: this capital, which contains non-fi

- Page 384 and 385: external capital (the customers - c

- Page 386 and 387: The image of the company Supply and

- Page 388 and 389: Infrastructure assets (corporate cu

- Page 390 and 391: Table 2. The analyzed elements of i

- Page 392 and 393: • as for the human capital, four

- Page 394 and 395: APPENDIX 1 The analyzed entities En

- Page 396 and 397: DETERMINANTS OF INTELLECTUAL CAPITA

- Page 398 and 399: from the work performed by a panel

- Page 400 and 401: Garcia-Meca et al. (2005) used univ

- Page 402 and 403: comprehensive in some industries, s

- Page 404 and 405: eliable data, a rigorous and transp

- Page 406 and 407: textile/clothing, and tourism/leisu

- Page 408 and 409: External (customer/relational) capi

- Page 410 and 411: This output shows for each of the 4

- Page 412 and 413: ICD_Index Equal variances assumed E

- Page 414 and 415: hypothesis H3 and thus we can state

- Page 416 and 417: Lang, M. and Lundholm, R. (1993)

- Page 418 and 419: IMPACTS AND CHANGES IN THE ACCOUNTI

- Page 420 and 421: the IAS adoption caused fundamental

- Page 422 and 423:

policies, we examined the net incom

- Page 424 and 425:

policy was established by the recog

- Page 426 and 427:

Table 2. IAS under examination, ten

- Page 428 and 429:

as tangible assets and their subseq

- Page 430 and 431:

Rahman, A., Perera, H. and Ganesh,

- Page 432 and 433:

PS10 Performance management Chairpe

- Page 434 and 435:

• comparative analysis between co

- Page 436 and 437:

investment in infrastructure, once

- Page 438 and 439:

Romtelecom has undergone a major tr

- Page 440 and 441:

LRIC models provide cost orientatio

- Page 442 and 443:

are primarily used for performance

- Page 444 and 445:

Dnes, A. (1995), “Post-privatizat

- Page 446 and 447:

considered under a different statem

- Page 448 and 449:

• The need to simulate efficient

- Page 450 and 451:

We considered this as well, by usin

- Page 452 and 453:

Aspect Focus Systems Development A

- Page 454 and 455:

Tabel 3. Internal process design Me

- Page 456 and 457:

the manager with the actual figures

- Page 458 and 459:

***http://www.isaca.org - IASCA sit

- Page 460 and 461:

The concept of sustainable developm

- Page 462 and 463:

Managers need to know all about the

- Page 464 and 465:

Table 3 Cumulative number of batche

- Page 466 and 467:

From another point of view, indicat

- Page 468 and 469:

Code has been modified through Law

- Page 470 and 471:

Another reason for termination of a

- Page 472 and 473:

and legal authorisations expired. H

- Page 474 and 475:

interdiction of dismissal can be ex

- Page 476 and 477:

Though dismissal due to professiona

- Page 478 and 479:

The rules regarding the collective

- Page 480 and 481:

If, on the contrary, the flexibilit

- Page 482 and 483:

PS11 Management information systems

- Page 484 and 485:

governments. The primary values of

- Page 486 and 487:

� with legacy applications- who n

- Page 488 and 489:

strategies behind the deployment of

- Page 490 and 491:

• iKP (Internet Keyed Payments Pr

- Page 492 and 493:

• Many alternative protocol paths

- Page 494 and 495:

specific problems are associated wi

- Page 496 and 497:

Boping, Z. & Shiyu, S., (2009), ”

- Page 498 and 499:

ehavior - meaning how to act over t

- Page 500 and 501:

Structuring the educational content

- Page 502 and 503:

pedagogical object is annotated usi

- Page 504 and 505:

associative). This aspect is repres

- Page 506 and 507:

Integration of ontologies Figure 5.

- Page 508 and 509:

Language) and an extension of RDF a

- Page 510 and 511:

Reviewing some relevant papers (Isf

- Page 512 and 513:

Figure 10. Ontology for detailing t

- Page 514 and 515:

Pernin, J.P. (2004) LOM, SCORM et I

- Page 516 and 517:

these documents are still difficult

- Page 518 and 519:

Figure 2. Framework for semantic an

- Page 520 and 521:

Figure 4. Semantic annotation using

- Page 522 and 523:

• It should verify the credential

- Page 524 and 525:

Each skill from the job offer ( ) i

- Page 526 and 527:

3.2. IT competency ontologies withi

- Page 528 and 529:

10. Computer network administrator

- Page 530 and 531:

items were required, such as ”Wor

- Page 532 and 533:

Hernandez, N. (2005), “Ontologies

- Page 534 and 535:

The current limitations in the qual

- Page 536 and 537:

The assurance of Business Intellige

- Page 538 and 539:

In the case study mentioned at tier

- Page 540 and 541:

improve performance. The ability to

- Page 542 and 543:

One key benefit to our system is th

- Page 544 and 545:

Grossmann Wilfried (2010), “A Con

- Page 546 and 547:

CORPORATE VALUES, THE COMPANIES’

- Page 548 and 549:

1.2. The Lack of Trust or the Crisi

- Page 550 and 551:

an impact on the individual behavio

- Page 552 and 553:

By making their corporate values pu

- Page 554 and 555:

The second situation appears when t

- Page 556 and 557:

geographical area. Regarding the fi

- Page 558 and 559:

sector ranked by market capitalizat

- Page 560 and 561:

ehaviour. Only few managers will ad

- Page 562 and 563:

Table 5. The value system of the Fr

- Page 564 and 565:

Anon, (2002b). “Most executives s

- Page 566 and 567:

HOW CAN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE MITIGA

- Page 568 and 569:

Studies on frauds have emphasized t

- Page 570 and 571:

environmental or situational factor

- Page 572 and 573:

and later in the documentation phas

- Page 574 and 575:

Knowing the factors that contribute

- Page 576 and 577:

• Have audit committee members pa

- Page 578 and 579:

� strengthen regulations as for e

- Page 580 and 581:

REFERENCES AICPA (2005) Management

- Page 582 and 583:

created by the new technology, by t

- Page 584 and 585:

Figure 2. Connection between compan

- Page 586 and 587:

The companies that meet the positiv

- Page 588 and 589:

employed, their families would lack

- Page 590 and 591:

Phishing. There are numerous traps

- Page 592 and 593:

competence and doesn’t understand

- Page 594 and 595:

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PRINCIPLES: AN

- Page 596 and 597:

• Executive directors should be a

- Page 598 and 599:

The corporate governance system in

- Page 600 and 601:

set out by the OECD in a general ma

- Page 602 and 603:

• 32% of the companies (21 out of

- Page 604 and 605:

Period Emerging economies and corpo

- Page 606 and 607:

• Customers: Most stakeholder mod

- Page 608 and 609:

and The Remuneration Committee cons

- Page 610 and 611:

CONCLUSIONS Starting from transpare

- Page 612 and 613:

Richard, B. and Miellet, D. (2002),

- Page 614 and 615:

IMPACT OF FUNDED STATUS OF PENSIONS

- Page 616 and 617:

wage level, national average earnin

- Page 618 and 619:

foreign currency in reserve currenc

- Page 620 and 621:

THE IMPACT OF UNREALISED FOREIGN EX

- Page 622 and 623:

y the foreign exchange differences

- Page 624 and 625:

However, the entity has not conduct

- Page 626 and 627:

What means "fictitious or non-distr

- Page 628 and 629:

difficult economic situation at gen

- Page 630 and 631:

VALUE RELEVANCE OF CONSOLIDATED VER

- Page 632 and 633:

market value relevance studies (Hel

- Page 634 and 635:

capital market as a whole, since th

- Page 636 and 637:

Share prices for the sampled observ

- Page 638 and 639:

Hypothesis 2: The value relevance o

- Page 640 and 641:

In order to test if an eventual rel

- Page 642 and 643:

Table 5. Correlation matrix of vari

- Page 644 and 645:

Table 7. Empirical results for regr

- Page 646 and 647:

Figure 2. Evolution of value releva

- Page 648 and 649:

(Francis, 1986: 394). We consider t

- Page 650 and 651:

Niskanen, J., Kinnunen, J. and Kasa

- Page 652 and 653:

must be able to accurately demonstr

- Page 654 and 655:

Market surveys show that the main p

- Page 656 and 657:

party, with only one condition: tha

- Page 658 and 659:

accounting activity. Also, professi

- Page 660 and 661:

PS14 Management information systems

- Page 662 and 663:

Due to these changes in the economy

- Page 664 and 665:

to the computer system, the acquisi

- Page 666 and 667:

The importance of IT Risk and Compl

- Page 668 and 669:

Factor - objective The Customer (In

- Page 670 and 671:

The security requirements for cloud

- Page 672 and 673:

Figure 5. General framework for inf

- Page 674 and 675:

ISMS Process (Source: Applying ISO

- Page 676 and 677:

greater confidence in the organizat

- Page 678 and 679:

Băbeanu D, (2008), Information str

- Page 680 and 681:

A TEST OF DIFFERENT MODELS FOR THE

- Page 682 and 683:

2003; Braga et al., 2007). For a re

- Page 684 and 685:

Where Y is the software effort, x i

- Page 686 and 687:

means that multiplying inputs x and

- Page 688 and 689:

The Desharnais dataset contains ele

- Page 690 and 691:

very far away from the predicted va

- Page 692 and 693:

Braga, P.L, Oliveira, A.L.I, Ribeir

- Page 694 and 695:

Sayyad Shirabad, J. and Menzies, T.

- Page 696 and 697:

First, during the development cycle

- Page 698 and 699:

If it’s calculated: Δk = CSIk -

- Page 700 and 701:

For emerging organizations, among t

- Page 702 and 703:

which connects is audited and the r

- Page 704 and 705:

THE EFFICIENCY OF SMALL AND MEDIUM

- Page 706 and 707:

1. LITERATURE REVIEW 1.1. Tendencie

- Page 708 and 709:

included in the category of develop

- Page 710 and 711:

It was interesting to discover whic

- Page 712 and 713:

2.2 Why are web-based applications

- Page 714 and 715:

Figure 1. Web based accounting arch

- Page 716 and 717:

From this module data are translate

- Page 718 and 719:

Table 2. The relation between the l

- Page 720 and 721:

Groza C., Briciu S., Cordos A.M, (2

- Page 722 and 723:

present the information, but is dif

- Page 724 and 725:

The second step was to establish th

- Page 726 and 727:

Academic Journals Total 5 Computer

- Page 728 and 729:

Table 4. Articles that mention XBRL

- Page 730 and 731:

and Kogan, 2010; Debreceny et al.,

- Page 732 and 733:

Hou, X., Hu. G, Ma, L., Liu, T., Pa

- Page 734 and 735:

15, 2009 on, the largest companies

- Page 736 and 737:

common base taxonomies like an IFRS

- Page 738 and 739:

Increasing comparability Improving

- Page 740 and 741:

3. INDEPENDENT VARIABLES DISCUSSION

- Page 742 and 743:

(1982) found no link between profit

- Page 744 and 745:

Table 1. Overview of Sample firms N

- Page 746 and 747:

information covers 40 items, non-fi

- Page 748 and 749:

No. Firms Overall Disclosures XBRL

- Page 750 and 751:

Table 4. Sample Characteristics Var

- Page 752 and 753:

Table 7. Model summaries for overal

- Page 754 and 755:

(Healy and Palepu 2001). Finally, t

- Page 756 and 757:

Gray, S., Meek, G. and Roberts, C.

- Page 758 and 759:

Trabelsi, S., Labelle, R. and Lauri

- Page 760 and 761:

OBLIGATION OR OPPORTUNITY FOR DRAWI

- Page 762 and 763:

IFRS for SMEs provides that, beside

- Page 764 and 765:

financial statements. We assume tha

- Page 766 and 767:

statements. The group of subjects w

- Page 768 and 769:

statements before, the questionnair

- Page 770 and 771:

Popa M. (2006), “Elemente sinteti

- Page 772 and 773:

INTRODUCTION The preparation of a s

- Page 774 and 775:

should also affect the recognition

- Page 776 and 777:

consolidated accounting remained in

- Page 778 and 779:

accounting regulations, for small a

- Page 780 and 781:

The standard published by IASB, in

- Page 782 and 783:

Chart 4. Q7 Responses Nevertheless,

- Page 784 and 785:

After processing the collected data

- Page 786 and 787:

(turnover, average number of employ

- Page 788 and 789:

ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES AND BOOK-TAX

- Page 790 and 791:

literally several provisions of the

- Page 792 and 793:

treatments. For instance, the share

- Page 794 and 795:

however to be enlarged upon and als

- Page 796 and 797:

4.5. Separate evaluation of assets

- Page 798 and 799:

Moreover, the legal documents suppo

- Page 800 and 801:

(Slemrod and Blumenthal, 1996). In

- Page 802 and 803:

D’Ascenzo, Michael; England, Andr

- Page 804 and 805:

Walker, D. I. (2007), „Financial

- Page 806 and 807:

FUNDAMENTAL DETERMINANTS OF CAPITAL

- Page 808 and 809:

companies, we found a statistical s

- Page 810 and 811:

The “free cash flow” term is th

- Page 812 and 813:

investments are "lumpy" and positiv

- Page 814 and 815:

estructuring process of the compani

- Page 816 and 817:

For the analysis model between the

- Page 818 and 819:

Table 4. Relationship between FL, T

- Page 820 and 821:

CONCLUSIONS There is no universal t

- Page 822 and 823:

IMPACT OF LONG-TERM INVESTMENT DECI

- Page 824 and 825:

1. PRESENTATION OF THE SCIENTIFIC P

- Page 826 and 827:

The equation shows that maintaining

- Page 828 and 829:

or expense. expense. ( * 100) N < (

- Page 830 and 831:

As we mentioned in the previous sub

- Page 832 and 833:

maintain the quality of the operati

- Page 834 and 835:

INCLUDING BEHAVIOURAL ELEMENTS IN A

- Page 836 and 837:

� the strong form - all informati

- Page 838 and 839:

Cognitive biases (Moderate) 3. COGN

- Page 840 and 841:

method with the next results: ancho

- Page 842 and 843:

3.7. Cognitive dissonance bias When

- Page 844 and 845:

versus development potential. The t

- Page 846 and 847:

This bias could determine the inves

- Page 848 and 849:

5.2. Anchoring bias You bought two

- Page 850 and 851:

• I am looking at the returns but

- Page 852 and 853:

• Even if I am very satisfied wit

- Page 854 and 855:

60 50 40 30 20 10 60 50 40 30 20 10

- Page 856 and 857:

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS The main

- Page 858 and 859:

Hirshleifer, D., Hou, K S., Teoh, H

- Page 860 and 861:

Sinha, G. (2005) „Training the br

- Page 862 and 863:

ACCOUNTING STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PER

- Page 864 and 865:

1. ACCOUNTING STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC

- Page 866 and 867:

principles class. A more particular

- Page 868 and 869:

As previously mentioned, the questi

- Page 870 and 871:

After developing the two methodolog

- Page 872 and 873:

Table 1. Students’ Academic Perfo

- Page 874 and 875:

Table 1. Students’ Academic Perfo

- Page 876 and 877:

etween the two calculated means to

- Page 878 and 879:

Cluster analysis being performed wi

- Page 880 and 881:

Mcduffie, S. and Smith, L.M (2006),

- Page 882 and 883:

Nobes and Parker (2008) argue that

- Page 884 and 885:

• The creation of a hierarchy of

- Page 886 and 887:

demanders of that education” (Ame

- Page 888 and 889:

The results of chi-square test appl

- Page 890 and 891:

ecommended by IES 2 (Content Progra

- Page 892 and 893:

REFERENCES The Academy of Economic

- Page 894 and 895:

naturally succeed on the organizati

- Page 896 and 897:

negotiation table, where they are t

- Page 898 and 899:

It is relatively easy to observe th

- Page 900 and 901:

Carr, C., (1990) Front-line Custome

- Page 902 and 903:

Figure 1. Social networking became

- Page 904 and 905:

1. LITERATURE REVIEW Formerly desig

- Page 906 and 907:

The base concept for Twitter is to

- Page 908 and 909:

2. STUDY METHODOLOGY Lee and McLoug

- Page 910 and 911:

Figure 7. Structure of the survey p

- Page 912 and 913:

Figure 10. Frequency of access (ema

- Page 914 and 915:

have to be better trained to protec

- Page 916 and 917:

ANNEX 1 Questionnaire on the impact

- Page 918 and 919:

The first works in Romanian, in the

- Page 920 and 921:

However, after 10 years, the Transy

- Page 922 and 923:

century when the economic life star

- Page 924 and 925:

first accounting manual written in

- Page 926 and 927:

category, and those of owners equit

- Page 928 and 929:

Cluj, also called College, was orga

- Page 930 and 931:

� the political influence and the

- Page 932 and 933:

Jinga, 1943:1). During its 14 years

- Page 934 and 935:

The accounting literature is rich a

- Page 936 and 937:

4.2.2. Influence of European practi

- Page 938 and 939:

Due to the foundation of the Academ

- Page 940 and 941:

PS19 Financial markets Chairperson

- Page 942 and 943:

attempt to predict future prices, n

- Page 944 and 945:

In the context of IFRS adoption, th

- Page 946 and 947:

Advisory Group (FCAG) which compris

- Page 948 and 949:

milestones that, if achieved, may l

- Page 950 and 951:

250 Japanese companies are listed o

- Page 952 and 953:

Graphic 1. Recent evolutions of DJI

- Page 954 and 955:

1 ˆ μ = T T ∑ i= 1 2 σ Tq and

- Page 956 and 957:

p values are computed directly from

- Page 958 and 959:

Cheung, K.C. and Coutts, J.A. (2001

- Page 960 and 961:

PROPERTIES OF ANALYSTS’ FORECASTS

- Page 962 and 963:

Several recent papers have showed t

- Page 964 and 965:

Observations Minimum Maximum Mean S

- Page 966 and 967:

Olimid. L., Ionaşcu M., Popescu L.

- Page 968 and 969:

� recognizing expenses in three p

- Page 970 and 971:

This study is structured in the fol

- Page 972 and 973:

eassessment, it is easily to make i

- Page 974 and 975:

only 9 companies have written out t

- Page 976 and 977:

• for calculation correlation deg

- Page 978 and 979:

Figure 1.The distribution of financ

- Page 980 and 981:

The 2 β coefficient in the formula

- Page 982 and 983:

Entities nomber Table 3. Difference

- Page 984 and 985:

coefficient, for both the correlati

- Page 986 and 987:

COMPANY NAME Balance sheet date Sto

- Page 988 and 989:

ANNEX 3 (amounts in pounds or centi

- Page 990 and 991:

EXPLORATORY STUDY ON SOCIAL AND ENV

- Page 992 and 993:

equirements with their implementati

- Page 994 and 995:

are motivated by national environme

- Page 996 and 997:

We created a database containing in

- Page 998 and 999:

process to implement at an extended

- Page 1000 and 1001:

We noticed that an important percen

- Page 1002 and 1003:

CSR sections in the annual report i

- Page 1004 and 1005:

CONCLUSIONS The qualitative aspects

- Page 1006 and 1007:

Lungu, C.I., Caraiani, C., Dascalu,

- Page 1008 and 1009:

into new territories, destruction c

- Page 1010 and 1011:

Attempts by economists to describe

- Page 1012 and 1013:

essential to establish a monotony p

- Page 1014 and 1015:

There is an observable prevalence o

- Page 1016 and 1017:

source and detect the sensor, givin

- Page 1018 and 1019:

stimulating system is manifesting,

- Page 1020 and 1021:

Decision-maker = Organized actions/

- Page 1022 and 1023:

Cline, W. R. (1992) The Economics o

- Page 1024 and 1025:

Vogtländer, J.,(2010) LCA-based as

- Page 1026 and 1027:

1. ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATION IN ROMA

- Page 1028 and 1029:

H5: The financial performance of en

- Page 1030 and 1031:

No. Environmental information detai

- Page 1032 and 1033:

environmental reporting than the en

- Page 1034 and 1035:

It can be thus concluded, that the

- Page 1036 and 1037:

CONCLUSIONS The level of environmen

- Page 1038 and 1039:

Gamble, G.O., Hsu, K., Kite, D. and

- Page 1040 and 1041:

APPENDIX 1 Description of the varia

- Page 1042 and 1043:

Compa 1 1 2 77 301563792 1860 1 2 2

- Page 1044 and 1045:

greater attachment to the area amon

- Page 1046 and 1047:

process of the compartment the info

- Page 1048 and 1049:

Figure 2. Table of the allocation o

- Page 1050 and 1051:

eallocation of the resources needed

- Page 1052 and 1053:

• point d), Non distributable val

- Page 1054 and 1055:

where: • IVCRSPam(t;s) = Intangib

- Page 1056 and 1057:

The same reflection concerns the en

- Page 1058 and 1059:

the function to compensate possible

- Page 1060 and 1061:

Giovanelli, F. and Di Bella, I. and

- Page 1062 and 1063:

THE IMPACT OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVEL

- Page 1064 and 1065:

too small, the revenues and, as a c

- Page 1066 and 1067:

the customers might refuse to pay o

- Page 1068 and 1069:

Among other financing sources, we c

- Page 1070 and 1071:

time, a rising fuel price will also

- Page 1072 and 1073:

Subsidies are granted in order to p

- Page 1074 and 1075:

energy comes to complete the conven

- Page 1076 and 1077:

EMPIRICAL STUDY REGARDING KEY INDIC

- Page 1078 and 1079:

Forum and Joint Research Centre of

- Page 1080 and 1081:

institutions show that investors te

- Page 1082 and 1083:

Minimum of 39.1 to a Maximum of 95.

- Page 1084 and 1085:

EPI 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 Figure

- Page 1086 and 1087:

The determination rapport (R-square

- Page 1088 and 1089:

Environmental challenges come in ma

- Page 1090 and 1091:

PS21 Management information systems

- Page 1092 and 1093:

1. INFORMATION The information assu

- Page 1094 and 1095:

2.1. The benefits of information

- Page 1096 and 1097:

2.3. How line managers use informat

- Page 1098 and 1099:

Figure 2. CATWOE illustration of in

- Page 1100 and 1101:

We can assume that the problems enu

- Page 1102 and 1103:

time deliveries between each link o

- Page 1104 and 1105:

• Reliability and safety. Paralle

- Page 1106 and 1107:

From the customer perspective an ER

- Page 1108 and 1109:

There are two methodologies for imp

- Page 1110 and 1111:

Hotăran, I. & Horga, G. (2010) “

- Page 1112 and 1113:

database vendors, is mainly about d

- Page 1114 and 1115:

• The first is the business aspec

- Page 1116 and 1117:

of it, to dig out meaningful relati

- Page 1118 and 1119:

Traditional analytical tools claim

- Page 1120 and 1121:

2.1 Analytics get more embedded int

- Page 1122 and 1123:

The most spread analytical tools fo

- Page 1124 and 1125:

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS Data con

- Page 1126 and 1127:

PS22 Management accounting Chairper

- Page 1128 and 1129:

in traditional management accountin

- Page 1130 and 1131:

in order to fulfil the needs of cen

- Page 1132 and 1133:

Very similar research had been perf

- Page 1134 and 1135:

Brierley, J.A., Cowton, C.J., Drury

- Page 1136 and 1137:

THE ROLE OF COSTS AND CONTROL IN EN

- Page 1138 and 1139:

Performance optimization is transla

- Page 1140 and 1141:

6. The value adding chain must assu

- Page 1142 and 1143:

This is why the size of the target

- Page 1144 and 1145:

To establish: 1. target cost and es

- Page 1146 and 1147:

When the business opportunities are

- Page 1148 and 1149:

an increase in profit equal to the

- Page 1150 and 1151:

THE CHANGE IN MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

- Page 1152 and 1153:

1. THE ANALYSIS OF CHANGE IN THE MA

- Page 1154 and 1155:

manner in which the speech is desig

- Page 1156 and 1157:

published in Romanian journals. The

- Page 1158 and 1159:

published on a particular segment,

- Page 1160 and 1161:

2003; GCF, 2003; AMIS), target cost

- Page 1162 and 1163:

Risk management 3 2 2.86 2 25 Inter

- Page 1164 and 1165:

From the research methodology point

- Page 1166 and 1167:

Glăvan, M., Brăescu (Dumitru), M.