axali da uaxlesi istoria

axali da uaxlesi istoria

axali da uaxlesi istoria

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

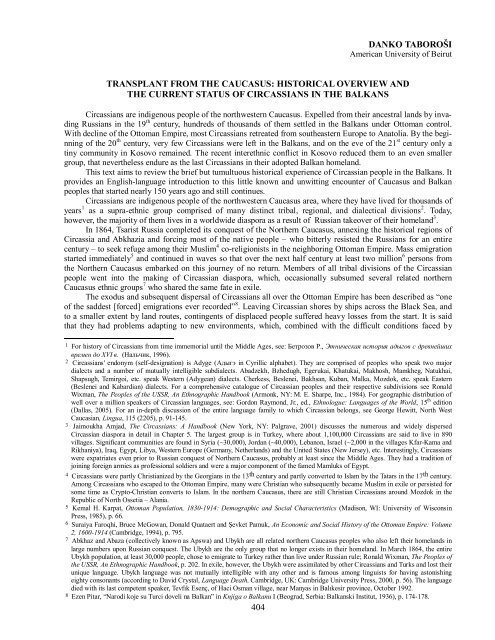

DANKO TABOROŠI<br />

American University of Beirut<br />

TRANSPLANT FROM THE CAUCASUS: HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND<br />

THE CURRENT STATUS OF CIRCASSIANS IN THE BALKANS<br />

Circassians are indigenous people of the northwestern Caucasus. Expelled from their ancestral lands by invading<br />

Russians in the 19 th century, hundreds of thousands of them settled in the Balkans under Ottoman control.<br />

With decline of the Ottoman Empire, most Circassians retreated from southeastern Europe to Anatolia. By the beginning<br />

of the 20 th century, very few Circassians were left in the Balkans, and on the eve of the 21 st century only a<br />

tiny community in Kosovo remained. The recent interethnic conflict in Kosovo reduced them to an even smaller<br />

group, that nevertheless endure as the last Circassians in their adopted Balkan homeland.<br />

This text aims to review the brief but tumultuous historical experience of Circassian people in the Balkans. It<br />

provides an English-language introduction to this little known and unwitting encounter of Caucasus and Balkan<br />

peoples that started nearly 150 years ago and still continues.<br />

Circassians are indigenous people of the northwestern Caucasus area, where they have lived for thousands of<br />

years 1 as a supra-ethnic group comprised of many distinct tribal, regional, and dialectical divisions 2 . To<strong>da</strong>y,<br />

however, the majority of them lives in a worldwide diaspora as a result of Russian takeover of their homeland 3 .<br />

In 1864, Tsarist Russia completed its conquest of the Northern Caucasus, annexing the historical regions of<br />

Circassia and Abkhazia and forcing most of the native people – who bitterly resisted the Russians for an entire<br />

century – to seek refuge among their Muslim 4 co-religionists in the neighboring Ottoman Empire. Mass emigration<br />

started immediately 5 and continued in waves so that over the next half century at least two million 6 persons from<br />

the Northern Caucasus embarked on this journey of no return. Members of all tribal divisions of the Circassian<br />

people went into the making of Circassian diaspora, which, occasionally subsumed several related northern<br />

Caucasus ethnic groups 7 who shared the same fate in exile.<br />

The exodus and subsequent dispersal of Circassians all over the Ottoman Empire has been described as “one<br />

of the saddest [forced] emigrations ever recorded” 8 . Leaving Circassian shores by ships across the Black Sea, and<br />

to a smaller extent by land routes, contingents of displaced people suffered heavy losses from the start. It is said<br />

that they had problems a<strong>da</strong>pting to new environments, which, combined with the difficult conditions faced by<br />

1 For history of Circassians from time immemorial until the Middle Ages, see: Бетрозов Р., Этническая история адыгов с древнейших<br />

времен до XVI в. (Нальчик, 1996).<br />

2 Circassians' endonym (self-designation) is Adyge (Адыгэ in Cyrillic alphabet). They are comprised of peoples who speak two major<br />

dialects and a number of mutually intelligible subdialects. Abadzekh, Bzhedugh, Egerukai, Khatukai, Makhosh, Mamkheg, Natukhai,<br />

Shapsugh, Temirgoi, etc. speak Western (Adygean) dialects. Cherkess, Beslenei, Bakhsan, Kuban, Malka, Mozdok, etc. speak Eastern<br />

(Beslenei and Kabardian) dialects. For a comprehensive catalogue of Circassian peoples and their respective subdivisions see Ronald<br />

Wixman, The Peoples of the USSR, An Ethnographic Handbook (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1984). For geographic distribution of<br />

well over a million speakers of Circassian languages, see: Gordon Raymond, Jr., ed., Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15 th edition<br />

(Dallas, 2005). For an in-depth discussion of the entire language family to which Circassian belongs, see George Hewitt, North West<br />

Caucasian, Lingua, 115 (2205), p. 91-145.<br />

3 Jaimoukha Amjad, The Circassians: A Handbook (New York, NY: Palgrave, 2001) discusses the numerous and widely dispersed<br />

Circassian diaspora in detail in Chapter 5. The largest group is in Turkey, where about 1,100,000 Circassians are said to live in 890<br />

villages. Significant communities are found in Syria (~30,000), Jor<strong>da</strong>n (~40,000), Lebanon, Israel (~2,000 in the villages Kfar-Kama and<br />

Rikhaniya), Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Western Europe (Germany, Netherlands) and the United States (New Jersey), etc. Interestingly, Circassians<br />

were expatriates even prior to Russian conquest of Northern Caucasus, probably at least since the Middle Ages. They had a tradition of<br />

joining foreign armies as professional soldiers and were a major component of the famed Mamluks of Egypt.<br />

4 Circassians were partly Christianized by the Georgians in the 13 th century and partly converted to Islam by the Tatars in the 17 th century.<br />

Among Circassians who escaped to the Ottoman Empire, many were Christian who subsequently became Muslim in exile or persisted for<br />

some time as Crypto-Christian converts to Islam. In the northern Caucasus, there are still Christian Circassians around Mozdok in the<br />

Republic of North Ossetia – Alania.<br />

5 Kemal H. Karpat, Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin<br />

Press, 1985), p. 66.<br />

6 Suraiya Faroqhi, Bruce McGowan, Donald Quataert and Şevket Pamuk, An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire: Volume<br />

2, 1600-1914 (Cambridge, 1994), p. 795.<br />

7 Abkhaz and Abaza (collectively known as Apswa) and Ubykh are all related northern Caucasus peoples who also left their homelands in<br />

large numbers upon Russian conquest. The Ubykh are the only group that no longer exists in their homeland. In March 1864, the entire<br />

Ubykh population, at least 30,000 people, chose to emigrate to Turkey rather than live under Russian rule; Ronald Wixman, The Peoples of<br />

the USSR, An Ethnographic Handbook, p. 202. In exile, however, the Ubykh were assimilated by other Circassians and Turks and lost their<br />

unique language. Ubykh language was not mutually intelligible with any other and is famous among linguists for having astonishing<br />

eighty consonants (according to David Crystal, Language Death, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 56). The language<br />

died with its last competent speaker, Tevfık Esenç, of Haci Osman village, near Manyas in Balıkesir province, October 1992.<br />

8 Ezen Pitar, “Narodi koje su Turci doveli na Balkan” in Knjiga o Balkanu I (Beograd, Serbia: Balkanski Institut, 1936), p. 174-178.<br />

404