- Page 1:

Reading akkadian PRayeRs & Hymns An

- Page 4 and 5:

ancient near east monographs Genera

- Page 6 and 7:

Copyright © 2011 by the society of

- Page 8 and 9:

Shuillas

- Page 11 and 12:

About This Book ALAN LENZI This boo

- Page 13 and 14:

ABOUT THIS BOOK gesammelt und herau

- Page 15 and 16:

ABOUT THIS BOOK Edition: Knowing th

- Page 17 and 18:

ABOUT THIS BOOK Annotations. At the

- Page 19:

ABOUT THIS BOOK Cuneiform. At the e

- Page 22 and 23:

xx READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 24 and 25:

xxii READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND H

- Page 27 and 28:

Introduction ALAN LENZI, CHRISTOPHE

- Page 29 and 30:

INTRODUCTION as a book, a desk, or

- Page 31 and 32:

INTRODUCTION Moreover, without some

- Page 33 and 34:

INTRODUCTION priest of a god, an au

- Page 35 and 36:

INTRODUCTION ideas upon them initia

- Page 37 and 38:

INTRODUCTION ritual speech prayer p

- Page 39 and 40:

INTRODUCTION or petitioning the dei

- Page 41 and 42:

INTRODUCTION As for the first text,

- Page 43 and 44:

INTRODUCTION In discussing these tw

- Page 45 and 46:

INTRODUCTION prayer based on a mode

- Page 47 and 48:

INTRODUCTION ritual speech prayer p

- Page 49 and 50:

INTRODUCTION prayers in this volume

- Page 51 and 52:

INTRODUCTION BaghM 34 (2003), 181-9

- Page 53 and 54:

INTRODUCTION divine images. 67 This

- Page 55 and 56:

INTRODUCTION ritual expert presided

- Page 57 and 58:

INTRODUCTION number of distinctive

- Page 59 and 60:

INTRODUCTION archival purposes, for

- Page 61 and 62:

INTRODUCTION The shuilla-rubric nam

- Page 63 and 64:

INTRODUCTION unsolicited evil signs

- Page 65 and 66:

INTRODUCTION Formally, namburbi-pra

- Page 67 and 68:

INTRODUCTION of this writing.} Kare

- Page 69 and 70:

INTRODUCTION dibbas were “designe

- Page 71 and 72:

INTRODUCTION return to normal” [o

- Page 73 and 74:

INTRODUCTION [t]he term ikribu must

- Page 75 and 76:

INTRODUCTION the ikribu-prayers and

- Page 77 and 78:

INTRODUCTION the OB period). 193 Th

- Page 79 and 80:

INTRODUCTION A standardized formula

- Page 81 and 82:

INTRODUCTION this introduction. Fir

- Page 83 and 84:

INTRODUCTION cations in annalistic

- Page 85 and 86:

INTRODUCTION of oaths, impartial ju

- Page 87 and 88:

INTRODUCTION THE USE OF AKKADIAN PR

- Page 89 and 90:

INTRODUCTION out-of-date. Still, hi

- Page 91 and 92:

INTRODUCTION „Gebetsbeschwörunge

- Page 93 and 94:

INTRODUCTION interpretation of the

- Page 95:

OLD BABYLONIAN TEXTS

- Page 98 and 99:

72 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 100 and 101:

74 1. pu-ul-lu-lu ru-bu-ú READING

- Page 102 and 103:

76 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 104 and 105:

78 21. li-iz-zi--ú-ma 22. i-na te-

- Page 106 and 107:

80 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 108 and 109:

82 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 111 and 112:

An OB Ikribu-Like Prayer to Shamash

- Page 113 and 114: 86 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 115 and 116: 88 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 117 and 118: 90 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 119 and 120: 92 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 121 and 122: 94 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 123 and 124: 96 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HYM

- Page 125 and 126: 98 62. d INANA be-le-et ta-ḫa-zi-

- Page 127 and 128: 100 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 129 and 130: AN OB IKRIBU-LIKE PRAYER TO SHAMASH

- Page 131 and 132: NINMUG:

- Page 133 and 134: 106 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 135: CUNEIFORM:

- Page 138 and 139: 112 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 140 and 141: 114 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 142 and 143: 116 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 144 and 145: 118 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 146 and 147: 120 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 148 and 149: 122 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 150 and 151: 124 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 152 and 153: 126 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 154 and 155: 128 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 156 and 157: 130 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 159 and 160: GHOSTS:

- Page 161 and 162: 134 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

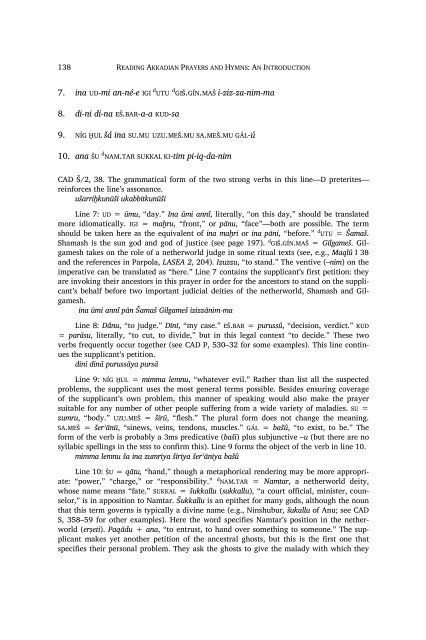

- Page 163: 136 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 167 and 168: 140 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 169 and 170: TRANSLATION:

- Page 171 and 172: GIRRA:

- Page 173 and 174: 146 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 175 and 176: 148 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 177 and 178: 150 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 179 and 180: 152 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 181 and 182: 154 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 183 and 184: 156 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 185 and 186: 158 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 187 and 188: 14. di-ni di-na a-lak-ti lim-da

- Page 189 and 190: 26. e-te-bi-ib az-za-ku ki-ma la-á

- Page 191 and 192: 164 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 193: 166 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 196 and 197: 170 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 198 and 199: 172 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 200 and 201: 174 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 202 and 203: 176 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 204 and 205: 178 CUNEIFORM: READING AKKADIAN PRA

- Page 206 and 207: 180 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 208 and 209: 182 ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY: READING

- Page 210 and 211: 184 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 212 and 213: 186 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 215 and 216:

SALT:

- Page 217 and 218:

190 THE PRAYER: READING AKKADIAN PR

- Page 219 and 220:

6. up-šá-še-e le-eʾ-bu-in-ni

- Page 221:

194 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 224 and 225:

198 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 226 and 227:

200 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 228 and 229:

202 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 230 and 231:

204 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 232 and 233:

206 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 234 and 235:

208 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 236 and 237:

210 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 238 and 239:

212 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 240 and 241:

214 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 243 and 244:

ANU:

- Page 245 and 246:

218 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 247 and 248:

220 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 249 and 250:

15. dà-lí-lí EN-iá lud-l[ul]

- Page 251 and 252:

224 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 253 and 254:

EA:

- Page 255 and 256:

228 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 257 and 258:

230 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 259 and 260:

9. d a-nu u d EN.LÍL ḫa-diš ri-

- Page 261 and 262:

18. at-mé-e-a li-ṭib UGU DINGIR

- Page 263 and 264:

236 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 265 and 266:

238 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 267 and 268:

240 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 269 and 270:

GULA:

- Page 271 and 272:

244 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 273 and 274:

246 ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY: READING

- Page 275 and 276:

248 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 277 and 278:

250 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 279 and 280:

252 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 281 and 282:

CUNEIFORM:

- Page 283 and 284:

ISHTAR: See page 169. THE PRAYER:

- Page 285 and 286:

258 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 287 and 288:

260 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 289 and 290:

262 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 291 and 292:

264 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 293 and 294:

266 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 295 and 296:

268 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 297 and 298:

270 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 299 and 300:

272 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 301 and 302:

274 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 303 and 304:

276 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 305 and 306:

278 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 307 and 308:

280 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 309 and 310:

282 TRANSLATION: READING AKKADIAN P

- Page 311 and 312:

CUNEIFORM:

- Page 313 and 314:

286 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 315 and 316:

288 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 317 and 318:

MARDUK:

- Page 319 and 320:

292 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 321 and 322:

294 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 323 and 324:

4. ša-su-ú u la a-pa-lu id-da-ṣ

- Page 325 and 326:

12. lu-ut-ta-id-ma gul-lul-tú la a

- Page 327 and 328:

300 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 329 and 330:

ana šùl-me u TI.LA piq-dan-ni

- Page 331 and 332:

304 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 333 and 334:

COMPARATIVE SUGGESTIONS:

- Page 335 and 336:

308 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 337:

310 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 340 and 341:

314 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 342 and 343:

316 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 344 and 345:

318 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 346 and 347:

320 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 348 and 349:

322 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 350 and 351:

324 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 352 and 353:

326 THE PRAYER: READING AKKADIAN PR

- Page 354 and 355:

328 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 356 and 357:

330 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 358 and 359:

332 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 360 and 361:

334 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 362 and 363:

336 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 365 and 366:

NERGAL:

- Page 367 and 368:

340 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 369 and 370:

6. ra-ba-ta ina É.KUR.ÚŠ ma-ḫi

- Page 371 and 372:

344 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 373 and 374:

25. ka-inim-ma šu-íl-lá d u-gur-

- Page 375:

348 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 378 and 379:

352 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 380 and 381:

354 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 382 and 383:

356 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 384 and 385:

358 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 386 and 387:

360 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 388 and 389:

362 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 390 and 391:

364 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 392 and 393:

366 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 394 and 395:

368 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 396 and 397:

370 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 398 and 399:

372 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 400 and 401:

374 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 402 and 403:

376 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 404 and 405:

378 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 406 and 407:

380 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 408 and 409:

382 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 410 and 411:

384 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 412 and 413:

386 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 414 and 415:

388 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 416 and 417:

390 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 418 and 419:

392 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 420 and 421:

394 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 422 and 423:

396 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 424 and 425:

398 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 426 and 427:

400 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 428 and 429:

402 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 430 and 431:

404 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 432 and 433:

406 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 434 and 435:

408 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 436 and 437:

410 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 438 and 439:

412 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 440 and 441:

414 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 442 and 443:

416 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 444 and 445:

418 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 447 and 448:

SHAMASH:

- Page 449 and 450:

422 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 451 and 452:

9. ŠU.II-ka-ma d UTU 10. a-na-ku

- Page 453 and 454:

426 15. TÚG.SÍG-ka aṣ-bat 16. i

- Page 455 and 456:

428 26. lid-lu-lu TE.ÉN READING AK

- Page 457 and 458:

430 CUNEIFORM: READING AKKADIAN PRA

- Page 459 and 460:

432 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 461 and 462:

3. me-e-ka am-te-eš ma-gal al-lik

- Page 463 and 464:

11. dan-na-at ŠU-ka a-ta-mar še-r

- Page 465 and 466:

20. DINGIR ag-gu lìb-ba-ka li-nu-

- Page 467 and 468:

440 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 469 and 470:

442 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 471:

444 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 474 and 475:

448 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 476 and 477:

450 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 478 and 479:

452 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 480 and 481:

454 28. ik-kib a-ku-lu 4 {ul i-de}

- Page 482 and 483:

456 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 484 and 485:

458 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 486 and 487:

460 COMPARATIVE SUGGESTIONS: READIN

- Page 488 and 489:

462 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 490 and 491:

464 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 492 and 493:

466 ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY: READING

- Page 494 and 495:

468 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 496 and 497:

470 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 498 and 499:

472 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 500 and 501:

474 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 502 and 503:

476 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 504 and 505:

478 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 506 and 507:

480 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 509 and 510:

MARDUK:

- Page 511 and 512:

484 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 513 and 514:

486 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 515 and 516:

488 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 517 and 518:

490 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 519 and 520:

492 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 521 and 522:

494 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 523 and 524:

496 READING AKKADIAN PRAYERS AND HY

- Page 525 and 526:

TRANSLATION:

- Page 527:

500 CUNEIFORM: READING AKKADIAN PRA

- Page 531 and 532:

Acrostics, 60 Adad, introduction to

- Page 533 and 534:

Berlejung, Angelika, 27, 105, 230,

- Page 535 and 536:

Loud, Gordon, 56 Luckenbill, Daniel

- Page 537 and 538:

MAYER’S INCANTATION-PRAYERS (besi

- Page 539 and 540:

Ishtar Queen of Heaven · 61 JNES 3

- Page 541 and 542:

HEBREW BIBLE Genesis 1:16, 253 1:26

- Page 543 and 544:

44:2, 195 44:7, 125 45:3,4, 240 45:

- Page 545 and 546:

130:6, 498 134:1-2, 239 136:9, 253

- Page 547:

There are few resources for student