- Page 2:

A..2^ BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM T

- Page 5:

Tracing from nature of a mesial lin

- Page 13 and 14:

TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE PREFAC

- Page 15 and 16:

§ 36. The Travelling Organs in Rel

- Page 17 and 18:

CONTENTS xi Rhythmic Movements—An

- Page 19 and 20:

CONTENTS xiii THE MOVEMENTS AND FUN

- Page 21 and 22:

§§ . CONTENTS XV INTELLIGENCE OF

- Page 23 and 24:

CONTENTS xvii THE OSSEOUS AND MUSCU

- Page 25 and 26:

§ 420. The Flight of Birds divisib

- Page 27 and 28:

PREFACE The present work has attain

- Page 29 and 30:

INTRODUCTION The present work natur

- Page 31 and 32:

INTRODUCTION xxv cules being so arr

- Page 33 and 34:

INTRODUCTION xxvii is the ancient w

- Page 35 and 36:

INTRODUCTION xxix ments met with in

- Page 37 and 38:

INTRODUCTION xxxi organisms there i

- Page 39 and 40:

DESIGN IN NATURE INORGANIC AND ORGA

- Page 41 and 42:

STRAIGHT-LINE AND OTHER FORMATIONS

- Page 43 and 44:

ARRANGEMENTS COMMON TO CRYSTALS, PL

- Page 45 and 46:

ARRANGEMENTS COMMON TO CRYSTALS, PL

- Page 47 and 48:

ARRANGEMENTS COMMON TO CRYSTALS, PL

- Page 49 and 50:

PREVALENCE OF SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS 1

- Page 51 and 52:

PREVALENCE OF SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS P

- Page 53 and 54:

PREVALENCE OF SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS P

- Page 55 and 56:

VOL. I PREVALENCE OF SPIRAL ARRANGE

- Page 57 and 58:

ORIGIN OF SPIRAL STRUCTURES 19 and

- Page 59 and 60:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN PLANTS 21 |3

- Page 61 and 62:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN PLANTS 23 PL

- Page 63 and 64:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN PLANTS PLATE

- Page 65 and 66:

Fig. 3. SPIRAL ARR'ANGEMENTS IN ANI

- Page 67 and 68:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN ANIMALS 29 P

- Page 69 and 70:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN ANIMALS PLAT

- Page 71 and 72:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN ANIMALS 33 P

- Page 73 and 74:

SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN ANIMALS Fir.

- Page 75 and 76:

CBERJtAU, SPIRAL ARRANGEMENTS IN AN

- Page 77 and 78:

RADIATING AND CONCENTRIC ARRANGEMEN

- Page 79 and 80:

RADIATING AND CONCENTRIC ARRANGEMEN

- Page 81 and 82:

RADIATING AND CONCENTRIC ARRANGEMEN

- Page 83 and 84:

1''IG. 1. RADIATING AND CONCENTRIC

- Page 85 and 86:

§ 9. Dendritic or Branching Moveme

- Page 87 and 88:

VOL. I, DENDRITIC OR BRANCHING ARRA

- Page 89 and 90:

DENDRITIC OR BRANCHING ARRANGEMENTS

- Page 91 and 92:

DENDRITIC OR BRANCHING ARRANGEMENTS

- Page 93 and 94:

DENDRITIC OR BRANCHING ARRANGEMENTS

- Page 95 and 96:

VOL. I. DENDRITIC OR BRANCHING ARRA

- Page 97 and 98:

BRANCHING AND RADIATING ARRANGEMENT

- Page 99 and 100:

BRANCHING AND RADIATING ARRANGEMENT

- Page 101 and 102:

HEXAGONAL STRUCTURES AND SEGMENTATI

- Page 103 and 104:

HEXAGONAL STRUCTURES 65 Fig. 20.—

- Page 105 and 106:

CLEAVAGE AND SEGMENTATION 67 PLATE

- Page 107 and 108:

LONGITUDINAL AND TRANSVERSE CLEAVAG

- Page 109 and 110:

CONVOLUTIONS IN HARD AND SOFT PARTS

- Page 111 and 112:

RADIATING AND BRANCHING ARRANGEMENT

- Page 113 and 114:

LONGITUDINAL AND TRANSVERSE CLEAVAG

- Page 115 and 116:

LONGITUDINAL, RADIATING, AND TRANSV

- Page 117 and 118:

LONGITUDINAL, RADIATING, AND TRANSV

- Page 119 and 120:

VOL. I. LONGITUDINAL AND RADIATING

- Page 121 and 122:

LONGITUDINAL, RADIATING, AND TRANSV

- Page 123 and 124:

TRAVELLING ORGANS FOR LAND, WATER,

- Page 125 and 126:

j^-«i Fig, S. FiG. Fig. 10. FIGURE

- Page 127 and 128:

vol.. I, RECAPITULATION 89 PLATE LI

- Page 129 and 130:

RECAPITULATION 91 The same thing, w

- Page 131 and 132:

ATOMS AND MOLECULES 93 some anthrop

- Page 133 and 134:

CONSERVATION OF ENERGY 95 secretion

- Page 135 and 136:

THE REPRODUCTIVE ELEMENTS OF PLANTS

- Page 137 and 138:

SPIRAL STRUCTURES AND MOVEMENTS IN

- Page 139 and 140:

ATOMS AND MOLECULES IN DEAD AND LIV

- Page 141 and 142:

UNITY OF PLAN IN NATURE 103 arrange

- Page 143 and 144:

force is so feeble that the chain o

- Page 145 and 146:

FIG. nG.4 FIG. 5 m^0'^i^ FIG. 6 FIG

- Page 147 and 148:

•'•'•;.v':^Hv'i4t^ ''•',>;'

- Page 149 and 150:

THE BAR-MAGNET iii number as polar

- Page 151 and 152:

THE COMPASS 113 of gelatine and pla

- Page 153 and 154:

MAGNETISM, ELECTRICITY, LIGHT, HEAT

- Page 155 and 156:

MAGNETISM, ELECTRICITY, LIGHT, HEAT

- Page 157 and 158:

ATMOSPHERIC AND OTHER ELECTRICITY 1

- Page 159 and 160:

ATMOSPHERIC AND OTHER ELECTRICITY 1

- Page 161 and 162:

ANIMAL MAGNETISM 123 the electric o

- Page 163 and 164:

LINES OF COMMUNICATION AND FORCE 12

- Page 165 and 166:

LINES OF COMMUNICATION AND FORCE 12

- Page 167 and 168:

LINES OF COMMUNICATION AND FORCE 12

- Page 169 and 170:

LINES OF COMMUNICATION AND FORCE 13

- Page 171 and 172:

A BEGINNINGS OF NERVOUS SYSTEM Fig.

- Page 173 and 174:

BEGINNINGS OF NERVOUS SYSTEM 135 So

- Page 175 and 176:

VOL I. ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND CELLS

- Page 177 and 178:

ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND CELLS AS FACT

- Page 179 and 180:

ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND CELLS AS FACT

- Page 181 and 182:

a' ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND CELLS AS F

- Page 183 and 184:

ATOMS, MOLECULES, AND CELLS AS FACT

- Page 185 and 186:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 187 and 188:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN. REPRODUCTIV

- Page 189 and 190:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 191 and 192:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 193 and 194:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 195 and 196:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 197 and 198:

EVIDENCES OF DESIGN IN REPRODUCTIVE

- Page 199 and 200:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 201 and 202:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 203 and 204:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 205 and 206:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 207 and 208:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 209 and 210:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 211 and 212:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 213 and 214:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 215 and 216:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 217 and 218:

ADVANCE IN LOWER PLANT AND ANIMAL F

- Page 219 and 220:

THE VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE WORLD i8i

- Page 221 and 222:

THE VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE WORLD 183

- Page 223 and 224:

NEW THEORY OF MATTER 185 " To obtai

- Page 225 and 226:

NEW THEORY OF MATTER 187 in action

- Page 227 and 228:

NEW THEORY OF MATTER 189 the outset

- Page 229 and 230:

INTERACTION BETWEEN MENTAL AND MATE

- Page 231 and 232:

MATTER AND FORCE IN INORGANIC AND O

- Page 233 and 234:

Molybdenum THE ELEMENTS AND THEIR C

- Page 235 and 236:

HAECKEL'S BELIEF IN THE OMNIPOTENCE

- Page 237 and 238:

HAECKEL'S BELIEF IN THE OMNIPOTENCE

- Page 239 and 240:

MECHANICAL VIEWS OF KANT AND LAPLAC

- Page 241 and 242:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 243 and 244:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 245 and 246:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 247 and 248:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 249 and 250:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 251 and 252:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 253 and 254:

PROFESSOR HUXLEY'S VIEWS ON EVOLUTI

- Page 255 and 256:

THE TRAVELLING ORGANS OF ANIMALS 21

- Page 257 and 258:

THE TRAVELLING ORGANS OF ANIMALS 21

- Page 259 and 260:

TRAVELLING ORGANS IN RELATION TO EN

- Page 261 and 262: KANT'S AND SPENCER'S VIEWS OF MATTE

- Page 263 and 264: KANT'S AND SPENCER'S VIEWS OF MATTE

- Page 265 and 266: SCRIPTURAL ACCOUNT OF CREATION 227

- Page 267 and 268: GEOLOGY AS BEARING ON CREATION 229

- Page 269 and 270: SIMPLE AND COMPLEX PLANTS AND ANIMA

- Page 271 and 272: PLANTS AND ANIMALS IMPROVABLE UP TO

- Page 273 and 274: EVERYTHING CONTROLLED AND UNDER SUP

- Page 275 and 276: THE UNIVERSE AS A WORKING SYSTEM 23

- Page 277 and 278: THE UNIVERSE AS A WORKING SYSTEM 23

- Page 279 and 280: ENVIRONMENT 241 To take other examp

- Page 281 and 282: INSTINCT 243 advance in plants and

- Page 283 and 284: INSTINCT AND INTELLIGENCE 245 custo

- Page 285 and 286: EFFECT OF COSMIC CHANGES ON PLANTS

- Page 287 and 288: RHYTHMIC MOVEMENTS IN PLANTS AND AN

- Page 289 and 290: RHYTHMIC MOVEMENTS IN PLANTS AND AN

- Page 291 and 292: THE MUSCULAR MOVEMENTS 253 the invo

- Page 293 and 294: THE MUSCULAR MOVEMENTS 255 From the

- Page 295 and 296: THE MUSCULAR MOVEMENTS 257 performe

- Page 297 and 298: NERVE REFLEXES IN ANIMALS 259 perfo

- Page 299 and 300: NERVE REFLEXES IN ANIMALS 261 movem

- Page 301 and 302: NERVE REFLEXES IN ANIMALS 263 forci

- Page 303 and 304: NERVE REFLEXES IN ANIMALS 265 and t

- Page 305 and 306: NERVE REFLEXES IN ANIMALS 267 taneo

- Page 307 and 308: RHYTHMIC MUSCLES 269 their parts, u

- Page 309 and 310: RHYTHMIC MUSCLES 271 That nerves in

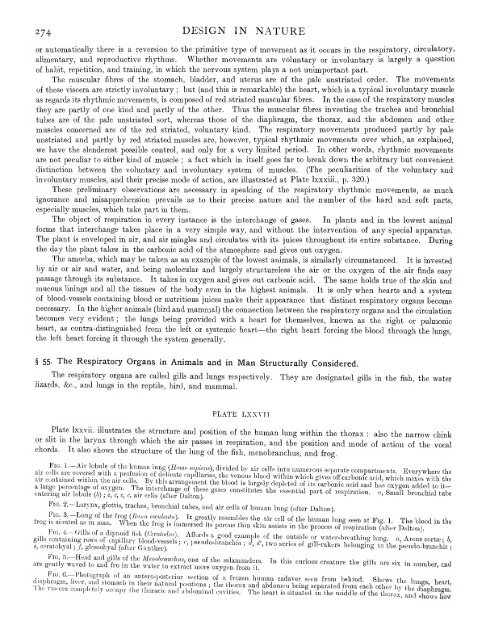

- Page 311: RESPIRATORY RHYTHMIC MOVEMENTS IN A

- Page 315 and 316: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 317 and 318: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 319 and 320: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 321 and 322: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 323 and 324: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISN OF RESPIR

- Page 325 and 326: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 327 and 328: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 329 and 330: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 331 and 332: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 333 and 334: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 335 and 336: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 337 and 338: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 339 and 340: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 341 and 342: NEW VIEW OF THE MECHANISM OF RESPIR

- Page 343 and 344: THE MYCETOZOA 305 great variety ; i

- Page 345 and 346: Pig. 62 (continued)— B. Gonooocci

- Page 347 and 348: THE MYCETOZOA H PLATE LXXX Fifi. 1.

- Page 349 and 350: Fig. 5, THE MYCETOZOA PLATE LXXXI F

- Page 351 and 352: PROTOPLASMIC, AMCEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 353 and 354: PROTOPLASMIC, AMOEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 355 and 356: PROTOPLASMIC, AMCEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 357 and 358: PROTOPLASMIC, AMCEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 359 and 360: PROTOPLASMIC, AMCEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 361 and 362: PROTOPLASMIC, AMCEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 363 and 364:

PROTOPLASMIC, AMGEBIC, AND OTHER MO

- Page 365 and 366:

MUSCULAR ACTION (VOLUNTARY AND INVO

- Page 367 and 368:

MUSCULAR ACTION (VOLUNTARY AND INVO

- Page 369 and 370:

MUSCULAR ACTION (VOLUNTARY AND INVO

- Page 371 and 372:

AMCEBA PROTEUS 333 The amcsba draws

- Page 373 and 374:

PARAMECIUM CAUDATUM 335 movements a

- Page 375 and 376:

GROMIA 337 spicules, &c. Similar va

- Page 377 and 378:

GROMIA 339 the very border line as

- Page 379 and 380:

GROMIA 34^ can be no doubt whatever

- Page 381 and 382:

GROMIA 343 The barramunda is credit

- Page 383 and 384:

ANIMALS ADAPTED FOR AIR AND WATER B

- Page 385 and 386:

A CREATOR AND DESIGNER NECESSARY TO

- Page 387 and 388:

A CREATOR AND DESIGNER NECESSARY TO

- Page 389 and 390:

A CREATOR AND DESIGNER NECESSARY TO

- Page 391 and 392:

DIVISION OF LABOUR IN RELATION TO D

- Page 393 and 394:

DIVISION OF LABOUR IN RELATION TO D

- Page 395 and 396:

DIVISION OF LABOUR IN RELATION TO D

- Page 397 and 398:

DESIGN A PROMINENT FACTOR IN NATURE

- Page 399 and 400:

DESIGN A PROMINENT FACTOR IN NATURE

- Page 401 and 402:

DESIGN A PROMINENT FACTOR IN NATURE

- Page 403 and 404:

DESIGN A PROMINENT FACTOR IN NATURE

- Page 405 and 406:

DESIGN IN THE REPRODUCTION AND GROW

- Page 407 and 408:

DESIGN IN THE REPRODUCTION AND GROW

- Page 409 and 410:

DESIGN IN THE REPRODUCTION AND GROW

- Page 411 and 412:

DESIGN IN THE REPRODUCTION AND GROW

- Page 413 and 414:

DESIGN IN THE REPRODUCTION AND GROW

- Page 415 and 416:

COMPOSITION OF THE HUMAN OVUM -i^jj

- Page 417 and 418:

§ 74. Fertilisation of the Ovum. F

- Page 419 and 420:

FERTILISATION OF THE OVUM 381 (d) T

- Page 421 and 422:

FERTILISATION OF THE OVUM PLATE LXX

- Page 423 and 424:

FERTILISATION OF THE OVUM 385 PLATE

- Page 425 and 426:

DIVISION OF THE IMPREGNATED OVUM 3^

- Page 427 and 428:

DEVELOPMENT OF EMBRYONIC MEMBRANES

- Page 429 and 430:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE HUMAN EMBRYO AND

- Page 431 and 432:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE HUMAN EMBRYO AND

- Page 433 and 434:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRAIN AND VESSEL

- Page 435 and 436:

PLACENTAL AND FCETAL CIRCULATION 39

- Page 437 and 438:

SUCCESSIVE CHANGES WITNESSED IN THE

- Page 439 and 440:

TRANSITION LINKS IN RELATION TO TYP

- Page 441 and 442:

TRANSITION LINKS IN RELATION TO TYP

- Page 443 and 444:

CHANGES IN, AND PECULIARITIES OF, T

- Page 445 and 446:

CHANGES IN, AND PECULIARITIES OF, T

- Page 447 and 448:

DEVELOPMENT OF BLOOD, &c., IN MAN A

- Page 449 and 450:

DEVELOPMENT OF BLOOD, &c., IN MAN A

- Page 451 and 452:

DEVELOPMENT OF BLOOD, &c., IN MAN A

- Page 453 and 454:

DESIGN IN MIGRATION OF BIRDS AND OT

- Page 455 and 456:

DESIGN IN THE PRODUCTION AND DISTRI

- Page 457 and 458:

DESIGN AS WITNESSED IN WINGED SEEDS

- Page 459 and 460:

RESEMBLANCES BETWEEN WINGED SEEDS A