The 21st Century climate challenge

The 21st Century climate challenge

The 21st Century climate challenge

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

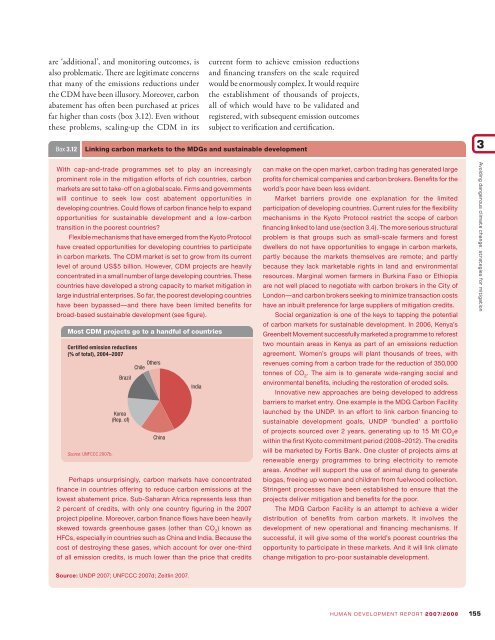

are ‘additional’, and monitoring outcomes, isalso problematic. <strong>The</strong>re are legitimate concernsthat many of the emissions reductions underthe CDM have been illusory. Moreover, carbonabatement has often been purchased at pricesfar higher than costs (box 3.12). Even withoutthese problems, scaling-up the CDM in itscurrent form to achieve emission reductionsand financing transfers on the scale requiredwould be enormously complex. It would requirethe establishment of thousands of projects,all of which would have to be validated andregistered, with subsequent emission outcomessubject to verification and certification.Box 3.12Linking carbon markets to the MDGs and sustainable development3With cap-and-trade programmes set to play an increasinglyprominent role in the mitigation efforts of rich countries, carbonmarkets are set to take-off on a global scale. Firms and governmentswill continue to seek low cost abatement opportunities indeveloping countries. Could flows of carbon finance help to expandopportunities for sustainable development and a low-carbontransition in the poorest countries?Flexible mechanisms that have emerged from the Kyoto Protocolhave created opportunities for developing countries to participatein carbon markets. <strong>The</strong> CDM market is set to grow from its currentlevel of around US$5 billion. However, CDM projects are heavilyconcentrated in a small number of large developing countries. <strong>The</strong>secountries have developed a strong capacity to market mitigation inlarge industrial enterprises. So far, the poorest developing countrieshave been bypassed—and there have been limited benefi ts forbroad-based sustainable development (see figure).Most CDM projects go to a handful of countriesCertified emission reductions(% of total), 2004–2007Source: UNFCCC 2007b.BrazilKorea(Rep. of)Chile OthersChinaIndiaPerhaps unsurprisingly, carbon markets have concentratedfi nance in countries offering to reduce carbon emissions at thelowest abatement price. Sub-Saharan Africa represents less than2 percent of credits, with only one country fi guring in the 2007project pipeline. Moreover, carbon finance flows have been heavilyskewed towards greenhouse gases (other than CO 2) known asHFCs, especially in countries such as China and India. Because thecost of destroying these gases, which account for over one-thirdof all emission credits, is much lower than the price that creditscan make on the open market, carbon trading has generated largeprofits for chemical companies and carbon brokers. Benefits for theworld’s poor have been less evident.Market barriers provide one explanation for the limitedparticipation of developing countries. Current rules for the flexibilitymechanisms in the Kyoto Protocol restrict the scope of carbonfinancing linked to land use (section 3.4). <strong>The</strong> more serious structuralproblem is that groups such as small-scale farmers and forestdwellers do not have opportunities to engage in carbon markets,partly because the markets themselves are remote; and partlybecause they lack marketable rights in land and environmentalresources. Marginal women farmers in Burkina Faso or Ethiopiaare not well placed to negotiate with carbon brokers in the City ofLondon—and carbon brokers seeking to minimize transaction costshave an inbuilt preference for large suppliers of mitigation credits.Social organization is one of the keys to tapping the potentialof carbon markets for sustainable development. In 2006, Kenya’sGreenbelt Movement successfully marketed a programme to reforesttwo mountain areas in Kenya as part of an emissions reductionagreement. Women’s groups will plant thousands of trees, withrevenues coming from a carbon trade for the reduction of 350,000tonnes of CO 2. <strong>The</strong> aim is to generate wide-ranging social andenvironmental benefits, including the restoration of eroded soils.Innovative new approaches are being developed to addressbarriers to market entry. One example is the MDG Carbon Facilitylaunched by the UNDP. In an effort to link carbon fi nancing tosustainable development goals, UNDP ‘bundled’ a portfolioof projects sourced over 2 years, generating up to 15 Mt CO 2ewithin the fi rst Kyoto commitment period (2008–2012). <strong>The</strong> creditswill be marketed by Fortis Bank. One cluster of projects aims atrenewable energy programmes to bring electricity to remoteareas. Another will support the use of animal dung to generatebiogas, freeing up women and children from fuelwood collection.Stringent processes have been established to ensure that theprojects deliver mitigation and benefi ts for the poor.<strong>The</strong> MDG Carbon Facility is an attempt to achieve a widerdistribution of benefi ts from carbon markets. It involves thedevelopment of new operational and fi nancing mechanisms. Ifsuccessful, it will give some of the world’s poorest countries theopportunity to participate in these markets. And it will link <strong>climate</strong>change mitigation to pro-poor sustainable development.Avoiding dangerous <strong>climate</strong> change: strategies for mitigationSource: UNDP 2007; UNFCCC 2007d; Zeitlin 2007.HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2007/2008 155