Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

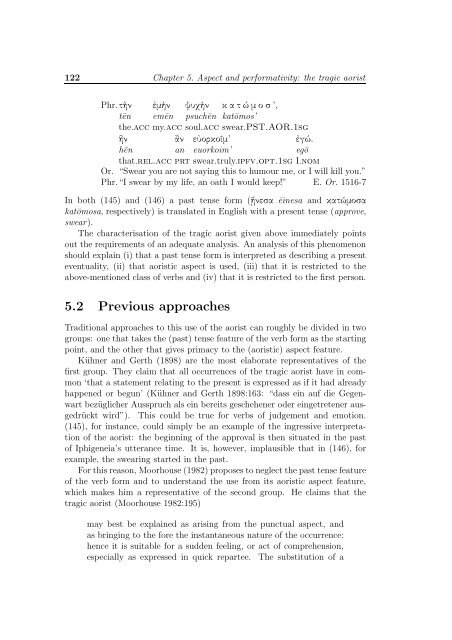

122 Chapter 5. <strong>Aspect</strong> and per<strong>for</strong>mativity: the tragic aoristPhr.τν µν ψυχν κ α τ ώ µ ο σ ,tēn emēn psuchēn katōmos’the.acc my.acc soul.acc swear.PST.AOR.1sgνhēnthat.rel.accνanprtεορκοµeuorkoim’swear.truly.ipfv.opt.1sgγώ.egōI.nomOr. “Swear you are not say<strong>in</strong>g this to humour me, or I will kill you.”Phr.“I swear by my life, an oath I would keep!” E. Or. 1516-7In both (145) and (146) a past tense <strong>for</strong>m (νεσα ē<strong>in</strong>esa and κατώµοσαkatōmosa, respectively) is translated <strong>in</strong> English with a present tense (approve,swear).The characterisation of the tragic aorist given above immediately po<strong>in</strong>tsout the requirements of an adequate analysis. An analysis of this phenomenonshould expla<strong>in</strong> (i) that a past tense <strong>for</strong>m is <strong>in</strong>terpreted as describ<strong>in</strong>g a presenteventuality, (ii) that aoristic aspect is used, (iii) that it is restricted to theabove-mentioned class of verbs and (iv) that it is restricted to the first person.5.2 Previous approachesTraditional approaches to this use of the aorist can roughly be divided <strong>in</strong> twogroups: one that takes the (past) tense feature of the verb <strong>for</strong>m as the start<strong>in</strong>gpo<strong>in</strong>t, and the other that gives primacy to the (aoristic) aspect feature.Kühner and Gerth (1898) are the most elaborate representatives of thefirst group. They claim that all occurrences of the tragic aorist have <strong>in</strong> common‘that a statement relat<strong>in</strong>g to the present is expressed as if it had alreadyhappened or begun’ (Kühner and Gerth 1898:163: “dass e<strong>in</strong> auf die Gegenwartbezüglicher Ausspruch als e<strong>in</strong> bereits geschehener oder e<strong>in</strong>getretener ausgedrücktwird”). This could be true <strong>for</strong> verbs of judgement and emotion.(145), <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>stance, could simply be an example of the <strong>in</strong>gressive <strong>in</strong>terpretationof the aorist: the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of the approval is then situated <strong>in</strong> the pastof Iphigeneia’s utterance time. It is, however, implausible that <strong>in</strong> (146), <strong>for</strong>example, the swear<strong>in</strong>g started <strong>in</strong> the past.For this reason, Moorhouse (1982) proposes to neglect the past tense featureof the verb <strong>for</strong>m and to understand the use from its aoristic aspect feature,which makes him a representative of the second group. He claims that thetragic aorist (Moorhouse 1982:195)may best be expla<strong>in</strong>ed as aris<strong>in</strong>g from the punctual aspect, andas br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>for</strong>e the <strong>in</strong>stantaneous nature of the occurrence:hence it is suitable <strong>for</strong> a sudden feel<strong>in</strong>g, or act of comprehension,especially as expressed <strong>in</strong> quick repartee. The substitution of a