Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

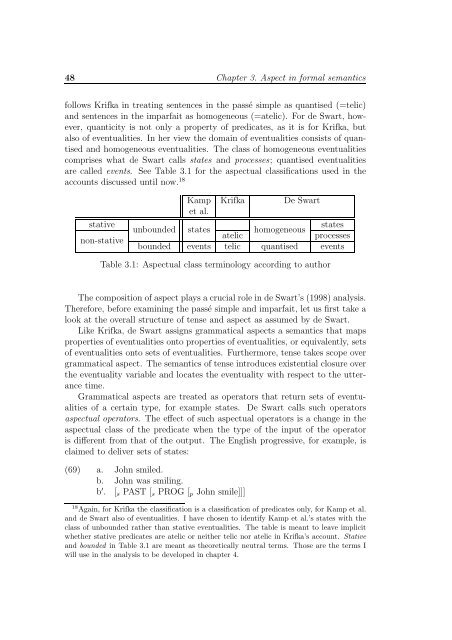

48 Chapter 3. <strong>Aspect</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal semanticsfollows Krifka <strong>in</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g sentences <strong>in</strong> the passé simple as quantised (=telic)and sentences <strong>in</strong> the imparfait as homogeneous (=atelic). For de Swart, however,quanticity is not only a property of predicates, as it is <strong>for</strong> Krifka, butalso of eventualities. In her view the doma<strong>in</strong> of eventualities consists of quantisedand homogeneous eventualities. The class of homogeneous eventualitiescomprises what de Swart calls states and processes; quantised eventualitiesare called events. See Table 3.1 <strong>for</strong> the aspectual classifications used <strong>in</strong> theaccounts discussed until now. 18 Kamp Krifka De Swartstativenon-stativeet al.unbounded statesstateshomogeneousatelicprocessesbounded events telic quantised eventsTable 3.1: <strong>Aspect</strong>ual class term<strong>in</strong>ology accord<strong>in</strong>g to authorThe composition of aspect plays a crucial role <strong>in</strong> de Swart’s (1998) analysis.There<strong>for</strong>e, be<strong>for</strong>e exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the passé simple and imparfait, let us first take alook at the overall structure of tense and aspect as assumed by de Swart.Like Krifka, de Swart assigns grammatical aspects a semantics that mapsproperties of eventualities onto properties of eventualities, or equivalently, setsof eventualities onto sets of eventualities. Furthermore, tense takes scope overgrammatical aspect. The semantics of tense <strong>in</strong>troduces existential closure overthe eventuality variable and locates the eventuality with respect to the utterancetime.Grammatical aspects are treated as operators that return sets of eventualitiesof a certa<strong>in</strong> type, <strong>for</strong> example states. De Swart calls such operatorsaspectual operators. The effect of such aspectual operators is a change <strong>in</strong> theaspectual class of the predicate when the type of the <strong>in</strong>put of the operatoris different from that of the output. The English progressive, <strong>for</strong> example, isclaimed to deliver sets of states:(69) a. John smiled.b. John was smil<strong>in</strong>g.b ′ . [ s PAST [ s PROG [ p John smile]]]18 Aga<strong>in</strong>, <strong>for</strong> Krifka the classification is a classification of predicates only, <strong>for</strong> Kamp et al.and de Swart also of eventualities. I have chosen to identify Kamp et al.’s states with theclass of unbounded rather than stative eventualities. The table is meant to leave implicitwhether stative predicates are atelic or neither telic nor atelic <strong>in</strong> Krifka’s account. Stativeand bounded <strong>in</strong> Table 3.1 are meant as theoretically neutral terms. Those are the terms Iwill use <strong>in</strong> the analysis to be developed <strong>in</strong> chapter 4.