Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Aspect in Ancient Greek - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

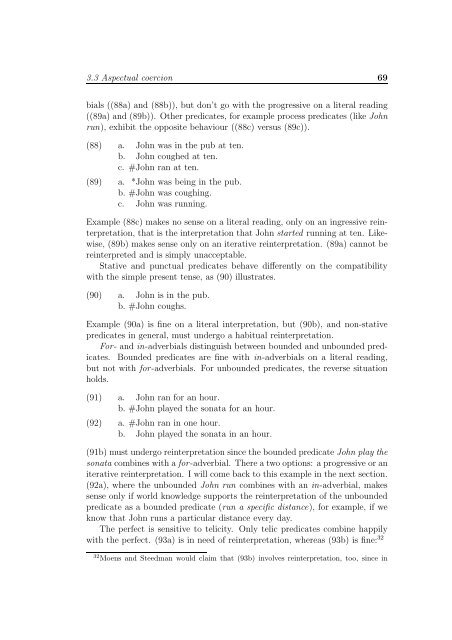

3.3 <strong>Aspect</strong>ual coercion 69bials ((88a) and (88b)), but don’t go with the progressive on a literal read<strong>in</strong>g((89a) and (89b)). Other predicates, <strong>for</strong> example process predicates (like Johnrun), exhibit the opposite behaviour ((88c) versus (89c)).(88) a. John was <strong>in</strong> the pub at ten.b. John coughed at ten.c. #John ran at ten.(89) a. *John was be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the pub.b. #John was cough<strong>in</strong>g.c. John was runn<strong>in</strong>g.Example (88c) makes no sense on a literal read<strong>in</strong>g, only on an <strong>in</strong>gressive re<strong>in</strong>terpretation,that is the <strong>in</strong>terpretation that John started runn<strong>in</strong>g at ten. Likewise,(89b) makes sense only on an iterative re<strong>in</strong>terpretation. (89a) cannot bere<strong>in</strong>terpreted and is simply unacceptable.Stative and punctual predicates behave differently on the compatibilitywith the simple present tense, as (90) illustrates.(90) a. John is <strong>in</strong> the pub.b. #John coughs.Example (90a) is f<strong>in</strong>e on a literal <strong>in</strong>terpretation, but (90b), and non-stativepredicates <strong>in</strong> general, must undergo a habitual re<strong>in</strong>terpretation.For- and <strong>in</strong>-adverbials dist<strong>in</strong>guish between bounded and unbounded predicates.Bounded predicates are f<strong>in</strong>e with <strong>in</strong>-adverbials on a literal read<strong>in</strong>g,but not with <strong>for</strong>-adverbials. For unbounded predicates, the reverse situationholds.(91) a. John ran <strong>for</strong> an hour.b. #John played the sonata <strong>for</strong> an hour.(92) a. #John ran <strong>in</strong> one hour.b. John played the sonata <strong>in</strong> an hour.(91b) must undergo re<strong>in</strong>terpretation s<strong>in</strong>ce the bounded predicate John play thesonata comb<strong>in</strong>es with a <strong>for</strong>-adverbial. There a two options: a progressive or aniterative re<strong>in</strong>terpretation. I will come back to this example <strong>in</strong> the next section.(92a), where the unbounded John run comb<strong>in</strong>es with an <strong>in</strong>-adverbial, makessense only if world knowledge supports the re<strong>in</strong>terpretation of the unboundedpredicate as a bounded predicate (run a specific distance), <strong>for</strong> example, if weknow that John runs a particular distance every day.The perfect is sensitive to telicity. Only telic predicates comb<strong>in</strong>e happilywith the perfect. (93a) is <strong>in</strong> need of re<strong>in</strong>terpretation, whereas (93b) is f<strong>in</strong>e: 3232 Moens and Steedman would claim that (93b) <strong>in</strong>volves re<strong>in</strong>terpretation, too, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong>