- Page 1 and 2:

45 th Annual Conference of the Inte

- Page 3 and 4:

ii A11. Krouse, S.L., and Irvine, J

- Page 5 and 6:

iv OCCUPATIONAL ANALYSIS APPLIED FO

- Page 7 and 8:

vi ANALYTICS C09a. Heffner, T.S.; T

- Page 9 and 10:

viii NATIONAL DEFENCE FORCE (S.A.N.

- Page 11 and 12:

x Minutes International Military Te

- Page 13 and 14:

xii BY-LAWS OF THE INTERNATIONAL MI

- Page 15 and 16:

xiv coordinating Primary Member. An

- Page 17 and 18:

USABILITY TESTING: LESSONS LEARNED

- Page 19 and 20:

the operational environment and, of

- Page 21 and 22:

Pill, J. (1970) “The Delphi Metho

- Page 23 and 24:

Types of definition There are diffe

- Page 25 and 26:

they may discuss components of it.

- Page 27 and 28:

It seems that in the absence of uni

- Page 29 and 30:

Do we assess what we want to assess

- Page 31 and 32:

Construct and criterion related val

- Page 33 and 34:

Results Due to the lack of a normal

- Page 35 and 36:

during ACABO. The question was ther

- Page 37 and 38:

Scholz, G. S., H. (1993). Das nomol

- Page 39 and 40:

There are not many studies with the

- Page 41 and 42:

6 Neuroticism 4.53 .56 .71 -.25 -.1

- Page 43 and 44:

-.37** Neuroticism -.38** Extravers

- Page 45 and 46:

Judge, T.A., Bono, J.E., & Locke, E

- Page 47 and 48:

y members of the occupational field

- Page 49 and 50:

performance value to lowest through

- Page 51 and 52:

comparing the two products; perhaps

- Page 53:

TP Questionnaire AFSC _____________

- Page 56 and 57:

40 Attachment 4 Respondent Comments

- Page 58:

42 References Institute for Job and

- Page 61 and 62:

• Austria also has committed itse

- Page 63 and 64:

INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS FORCES ENT

- Page 65 and 66:

JOB-SPECIFIC PERSONALITY ATTRIBUTES

- Page 67 and 68:

Canadian Forces. Results indicated

- Page 69 and 70:

Table 1. The NCOPI Dimensions and G

- Page 71 and 72:

Table 2. Correlations Between Perso

- Page 73 and 74:

To examine the relationship between

- Page 75 and 76:

correlates of psychological well-be

- Page 77 and 78:

Thomas, J. L., Dickson, M. W., & Bl

- Page 79 and 80:

more counterproductive behaviors, a

- Page 81 and 82:

dimension (e.g., maintain mechanica

- Page 83 and 84:

judged by trained raters). The resu

- Page 85 and 86:

Lightfoot, M.A., Alley, W.E., Schul

- Page 87 and 88:

abnormal positions such as spins an

- Page 89 and 90:

Description of OZ -----------------

- Page 91 and 92:

-----------------------------------

- Page 93 and 94:

-----------------------------------

- Page 95 and 96:

Procedure: Data collection consiste

- Page 97 and 98:

Fig. 4b: Heading performance of the

- Page 99 and 100:

Fig. 5b: Heading performance of the

- Page 101 and 102:

Fig. 6a: Altitude performance of th

- Page 103 and 104:

Discussion The most important concl

- Page 105 and 106:

12. Hoffman, R. R., Ford, K. M., an

- Page 107 and 108:

PERCEPTUAL DRIFT RELATED TO SPATIAL

- Page 109 and 110:

indicated by the negative values. T

- Page 111 and 112:

Dizio, P., Li, W., Lackner, J.R. &

- Page 113 and 114:

Psychologically, the victim of perc

- Page 115 and 116:

Individualized colored filters seem

- Page 117 and 118:

e remembered, however, that Irlen o

- Page 119 and 120:

Neurofeedback Training for Two Dime

- Page 121 and 122:

conserved. We can determine both Co

- Page 123 and 124:

sophisticated equipment and technol

- Page 125 and 126:

Figure 1: Changes in Concentration

- Page 127 and 128:

WHAT TODAY’S SOLDIERS TELL US ABO

- Page 129 and 130:

troubleshoot interconnectivity prob

- Page 131 and 132:

What advantages do Soldiers rate as

- Page 133 and 134:

This new training process viewed th

- Page 135 and 136:

collection and analysis. Also inclu

- Page 137 and 138:

CONCLUSION Figure 4: Sample Distrib

- Page 139 and 140:

RACE AND GENDER AS FACTORS IN FLIGH

- Page 141 and 142:

egression equation. The process was

- Page 143 and 144:

DISCUSSION These studies found that

- Page 145 and 146:

Validation of an Unmanned Aerial Ve

- Page 147 and 148:

direction, and stick movement produ

- Page 149 and 150:

References Biggerstaff, S., Blower,

- Page 151 and 152:

Table 2. Correlations and descripti

- Page 153 and 154:

Figure 1. Stick, rudder, and thrott

- Page 155 and 156:

Figure 3. Scatterplot of index scor

- Page 157 and 158:

The application of new information

- Page 159 and 160:

Communication. Recent research has

- Page 161 and 162:

of situation in which Soldiers woul

- Page 163 and 164:

An analysis of variance was perform

- Page 165 and 166:

Hevel, J. R. (2002). The Objective

- Page 167 and 168:

affective (or attitudinal) componen

- Page 169 and 170:

e1 e2 e3 Q53K .36 e4 e5 Q53I Q53J .

- Page 171 and 172:

REFERENCES Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J

- Page 173 and 174:

Rumsey, M.G. (1995). The best they

- Page 175 and 176:

(1999) found that among members in

- Page 177 and 178:

Results Satisfaction with the Milit

- Page 179 and 180:

Spouse/significant other support to

- Page 181 and 182:

quality of life in the Air Force, a

- Page 183 and 184:

BRITISH ARMY LEAVERS SURVEY: AN INV

- Page 185 and 186:

would be better, and that there wou

- Page 187 and 188:

ABSTRACT PREDICTORS OF U.S. ARMY CA

- Page 189 and 190:

Survey items were then aggregated i

- Page 191 and 192:

expects them to be committed, they

- Page 193 and 194:

THE IMPORTANCE OF A FAMILY-FRIENDLY

- Page 195 and 196:

multiple life roles (Kahn, Wolfe, Q

- Page 197 and 198:

consequently feel they are unable t

- Page 199 and 200:

perceptions of the usability of wor

- Page 201 and 202:

family-friendly work environment pe

- Page 203 and 204:

Previous studies have found that on

- Page 205 and 206:

For both employees with high family

- Page 207 and 208:

Figure 3 Interaction between FFWE,

- Page 209 and 210:

differently in the military compare

- Page 211 and 212:

Castro, C. A., Adler, A. B., & Bien

- Page 213 and 214:

Kossek, E. E., & Lobel, S. (1996).

- Page 215 and 216:

Tracking U.S. Navy Reserve Career D

- Page 217 and 218:

menus, a commander or career counse

- Page 219 and 220:

Respondents were divided in their r

- Page 221 and 222:

Duties and Functions of a Recruitin

- Page 223 and 224:

The in-house coaching provided to s

- Page 225 and 226:

Metrics of Unprofessional, Gender-R

- Page 227 and 228:

Regardless of paygrade, both women

- Page 229 and 230:

military installation. However, wom

- Page 231 and 232:

Table 6 Frequency of Reporting Beha

- Page 233 and 234:

action was taken against the offend

- Page 235 and 236:

Workplace Reprisals: A Model of Ret

- Page 237 and 238:

INCIDENCE OF RETALIATION Studies de

- Page 239 and 240:

Far less is known about the consequ

- Page 241 and 242:

METHOD Participants and Procedure T

- Page 243 and 244:

Subjective Appraisal The subjective

- Page 245 and 246:

RESULTS Exploratory Model The range

- Page 247 and 248:

More frequent occurrences of UGRB,

- Page 249 and 250:

organizational commitment and psych

- Page 251 and 252:

Fitzgerald, L.F., Drasgow, F., Huli

- Page 253 and 254:

UNDERSTANDING RESPONSES TO SEXUAL H

- Page 255 and 256:

sample population was selected thro

- Page 257 and 258:

Finally individuals were identified

- Page 259 and 260:

less likely to indicate they had ex

- Page 261 and 262:

● Non-Reporters < Reporters Figur

- Page 263 and 264:

eport (Other). Items endorsed in bo

- Page 265 and 266:

policy and procedure relevant to ha

- Page 267 and 268:

Justice Versus Gender Socialization

- Page 269 and 270:

Table of Contents Table of Contents

- Page 271 and 272:

1.1 Purpose 1.0 Introduction This p

- Page 273 and 274:

The Department of National Defence

- Page 275 and 276:

2.1 Stakeholder Brainstorming The f

- Page 277 and 278:

2.2 Stakeholder Influence and Impor

- Page 279 and 280:

Figure 3 graphically represents sta

- Page 281 and 282:

The SIS is a ‘research process ma

- Page 283 and 284:

3.2.1 The SIS Online As already men

- Page 285 and 286:

stakeholder groups. Furthermore, th

- Page 287 and 288:

INTRODUCTION DESIGNING A NEW HR SYS

- Page 289 and 290:

homogeneity of work activities with

- Page 291 and 292:

empirical information from the work

- Page 293 and 294:

eviewed by NIMA management and othe

- Page 295 and 296:

Observations made as a result of a

- Page 297 and 298:

45 th 3. Generating the specific qu

- Page 299 and 300:

Strategies for Increased Reporting

- Page 301 and 302:

of information technology systems.

- Page 303 and 304:

Guide for Reporting Counterintellig

- Page 305 and 306:

CHARACTERIZING INFORMATION SYSTEMS

- Page 307 and 308:

In about 60% of these recorded even

- Page 309 and 310:

following example, however, a cadet

- Page 311 and 312:

The most significant event of this

- Page 313 and 314:

Ten Technological, Social, and Econ

- Page 315 and 316:

can provide motivation and opportun

- Page 317 and 318:

Requirement Inspection of MASS ques

- Page 319 and 320:

Finally, third level questions woul

- Page 321 and 322:

OCCUPATIONAL ANALYSIS APPLIED FOR T

- Page 323 and 324:

CLASSIFICATION OF DUTIES INTO NEW S

- Page 325 and 326:

CONCLUSIONS The procedure described

- Page 327 and 328:

For each of the 27 items, the respo

- Page 329 and 330:

Table 1: Misclassification rates fo

- Page 331 and 332:

y examining all of the possible cos

- Page 333 and 334:

PREDICTING ATTRITION OF ARMY RECRUI

- Page 335 and 336:

1 1 P( vi = jθ = t) = − , 1+ exp

- Page 337 and 338:

It can be seen that for this AIM sc

- Page 339 and 340:

A NEW APPROACH TO CONSTRUCTING AND

- Page 341 and 342:

stimulus t, and is considered a pos

- Page 343 and 344:

items involving stimuli on dimensio

- Page 345 and 346:

Roberts, J. S., Donoghue, J. R., &

- Page 347 and 348:

viewed as a combination of two to t

- Page 349 and 350: e1 e2 e3 Q53K .36 e4 e5 Q53I Q53J .

- Page 351 and 352: REFERENCES Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J

- Page 353 and 354: impossible for people to hide their

- Page 355 and 356: Nederhof .52 ( 2003) 13 items 16 .7

- Page 357 and 358: The relationship between behaviour

- Page 359 and 360: However, possibilities are seen to

- Page 361 and 362: Article structure This paper descri

- Page 363 and 364: Figure 1. Simplified version of the

- Page 365 and 366: - My home front is proud of me. - M

- Page 367 and 368: Organizational aspects Appreciation

- Page 369 and 370: PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE DUTCH

- Page 371 and 372: efore reporting the results. b) Alt

- Page 373 and 374: LITERATURE Avenarius, M.J.H. (1994)

- Page 375 and 376: In particular it was identified tha

- Page 377 and 378: number of items to decrease the len

- Page 379 and 380: A randomly selected sample of 1,500

- Page 381 and 382: • When total wellbeing scores wer

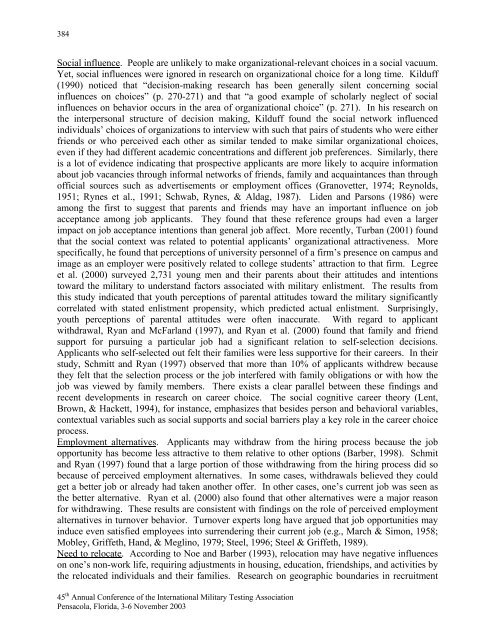

- Page 383 and 384: significantly better recruits for a

- Page 385 and 386: • Non-zero Payoff: The number of

- Page 387 and 388: The ordinates indicate the average

- Page 389 and 390: In next- rather busy - graph the av

- Page 391 and 392: vacancies. In fact, the problem of

- Page 393 and 394: • Lescrève, F., The Selection of

- Page 395 and 396: Vacancies per trade (Columns) for e

- Page 397 and 398: From Attraction to Rejection: A Qua

- Page 399: Saks, & Summers, 1991). Bretz and J

- Page 403 and 404: information he/she had received, (c

- Page 405 and 406: is not uncommon that applicants nee

- Page 407 and 408: the primary motive for withdrawal.

- Page 409 and 410: References Anderson, N., Born, M.,

- Page 411 and 412: Noe, R.A., Steffy, B.D., & Barber,

- Page 413 and 414: Wanous, J.P. (1992). Organizational

- Page 415 and 416: We also have under way a predictive

- Page 417 and 418: For the validation analyses, a fina

- Page 419 and 420: NLSI IMPLEMENTATION TO A WEB-BASED

- Page 421 and 422: work at the sentence level. This am

- Page 423 and 424: The semantic module: MRS and LKB Th

- Page 425 and 426: Next the program has to deal with

- Page 427 and 428: Conclusion Communication abilities

- Page 429 and 430: Exam Center to work with the projec

- Page 431 and 432: exam. Gateway was able to provide t

- Page 433 and 434: questions is monitored statisticall

- Page 435 and 436: 3. Computerized testing has been sh

- Page 437 and 438: 3. Most publishers have chosen not

- Page 439 and 440: should not house permanent cookies

- Page 441 and 442: Figure 2. Five process model per in

- Page 443 and 444: Results As of October 2003, the TSA

- Page 445 and 446: Klion, R., Pfenninger, D., Chiocchi

- Page 447 and 448: STREAMLINING OF THE NAVY ENLISTED A

- Page 449 and 450: and compared with the number found

- Page 451 and 452:

March 2002 marked the implementatio

- Page 453 and 454:

Due to the limited bandwidth restri

- Page 455 and 456:

their tests. However, job seekers o

- Page 457 and 458:

they may already have in relation t

- Page 459 and 460:

way both in and out of school. A si

- Page 461 and 462:

The students were asked about their

- Page 463 and 464:

This work was funded by the Human S

- Page 465 and 466:

AIR’s past experienced in the IC

- Page 467 and 468:

obtain the necessary clearances nec

- Page 469 and 470:

As we move forward with integrating

- Page 471 and 472:

ENCAPS - Using Non-Cognitive Measur

- Page 473 and 474:

cognitive ability. One particularly

- Page 475 and 476:

classification of enlisted personne

- Page 477 and 478:

Abstract Pilot Selection in the Aus

- Page 479 and 480:

Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and Roy

- Page 481 and 482:

comprising the ATB pilot index (PI)

- Page 483 and 484:

References Bongers, S., and Pei, J.

- Page 485 and 486:

The Armed Services Vocational Aptit

- Page 487 and 488:

Attachment A Career Exploration Pro

- Page 489 and 490:

References Harmon, L. W., Hansen, J

- Page 491 and 492:

Watson, 2002; Dawis, 1991), or perh

- Page 493 and 494:

7 community interest elements, and

- Page 495 and 496:

Figure 3. Illustration of possible

- Page 497 and 498:

Vocational Interest Measurement in

- Page 499 and 500:

Usability Testing II The second pha

- Page 501 and 502:

THE ARMY VOCATIONAL INTEREST CAREER

- Page 503 and 504:

soldiers who left the Army for avoi

- Page 505 and 506:

the cross-validation sample. Since

- Page 507 and 508:

DEVELOPING MEASURES OF OCCUPATIONAL

- Page 509 and 510:

For Select21 we conceived of a nove

- Page 511 and 512:

1998). For example, nearly all of t

- Page 513 and 514:

potential benefit of including such

- Page 515 and 516:

OCCUPATIONAL SURVEY SUPPORT OF AIR

- Page 517 and 518:

tasks. The structure of jobs within

- Page 519 and 520:

AFSC 2A3X1 (A-10, F-15, U-2 AVIONIC

- Page 521 and 522:

Occupational Analytics Paul L. Jone

- Page 523 and 524:

Anticipating the Future for First-T

- Page 525 and 526:

now exist. Therefore, we had to der

- Page 527 and 528:

perhaps deserves note. This is the

- Page 529 and 530:

Sager, C. E., Russell, T. L., Campb

- Page 531 and 532:

The primary goal of selection/class

- Page 533 and 534:

Knowledges, Skills, and Attributes

- Page 535 and 536:

of anticipated future conditions ap

- Page 537 and 538:

REFERENCES Campbell, J. P., & Knapp

- Page 539 and 540:

SMEs to think of Soldiers they supe

- Page 541 and 542:

on a rating, while others use the H

- Page 543 and 544:

fairly easy to identify first-level

- Page 545 and 546:

eviewers considered the currency of

- Page 547 and 548:

DEVELOPING OPERATIONAL PERSONALITY

- Page 549 and 550:

In this paper, we focus on two meas

- Page 551 and 552:

Here, we score only those statement

- Page 553 and 554:

understanding how applicants might

- Page 555 and 556:

Putka, D.J., Kilcullen, R. N., & Wh

- Page 557 and 558:

of personality. Second, the same re

- Page 559 and 560:

Table 1. Correlations between Civil

- Page 561 and 562:

The latent structure underlying the

- Page 563 and 564:

There are many ways to score a situ

- Page 565 and 566:

ASSESSING PERSON-ENVIRONMENT (P-E)

- Page 567 and 568:

To develop the ADI, we first identi

- Page 569 and 570:

Army to provide it, and a second wh

- Page 571 and 572:

APPENDIX Example Item from the Work

- Page 573 and 574:

To achieve wide-scale implementatio

- Page 575 and 576:

team leadership; concern for Soldie

- Page 577 and 578:

1 ST WATCH: ASSESSMENT OF COPING ST

- Page 579 and 580:

assess individuals’ personal valu

- Page 581 and 582:

eported being most likely to use th

- Page 583 and 584:

1 st WATCH: THE NAVY FIT SCALE Mart

- Page 585 and 586:

Surveys RTC Grad Survey. This quest

- Page 587 and 588:

Hypothesis 3 stated that recruits w

- Page 589 and 590:

USING RESULTS FROM ATTITUDE AND OPI

- Page 591 and 592:

Using Survey and Interview Data: An

- Page 593 and 594:

Conclusions and Recommendations Thi

- Page 595 and 596:

Table 2 Percent of officers and enl

- Page 597 and 598:

UTILIZING SURVEY RESULTS OF THE NAV

- Page 599 and 600:

assessed by the survey. This notion

- Page 601 and 602:

original sample providing them with

- Page 603 and 604:

THE U.S. ARMY'S PERSONNEL REPLACEME

- Page 605 and 606:

This policy was so strictly adhered

- Page 607 and 608:

The Army has over 180,000 soldiers

- Page 609 and 610:

Since 1990 a lot of work has been d

- Page 611 and 612:

Results The internal consistency of

- Page 613 and 614:

A F II Coordinat or F III Scout F I

- Page 615 and 616:

Abstract Mental Health Literacy in

- Page 617 and 618:

of self-treatments and of professio

- Page 619 and 620:

the number of items to decrease the

- Page 621 and 622:

• Gender - 87.6% males, 12.4% fem

- Page 623 and 624:

ADF 60 , and community drug use rat

- Page 625 and 626:

The survey was re-administered in t

- Page 627 and 628:

The perceived moral intensity scale

- Page 629 and 630:

organization has significant contro

- Page 631 and 632:

ADAPTING OCCUPATIONAL ANALYSIS METH

- Page 633 and 634:

are not improved for the long term,

- Page 635 and 636:

Gateworth, R.D., & Field,H.S. (1998

- Page 637 and 638:

Inevitably, new technology will be

- Page 639 and 640:

experimentation report. The structu

- Page 641 and 642:

esponsibilities involved in this po

- Page 643 and 644:

Comparison of Tasks and Knowledge D

- Page 645 and 646:

angle of approach to the target may

- Page 647 and 648:

Transformational Leadership: Relati

- Page 649 and 650:

concentrate their efforts on longer

- Page 651 and 652:

levels of analysis (e.g., Klein, Da

- Page 653 and 654:

soldiers constituted 39 combat team

- Page 655 and 656:

performance domains at the same lev

- Page 657 and 658:

performance was significantly stron

- Page 659 and 660:

The finding that transformational l

- Page 661 and 662:

A third limitation is the relativel

- Page 663 and 664:

Devine, D.J., Clayton, L.D., Philip

- Page 665 and 666:

Ostroff, C., & Schmitt, N. (1993).

- Page 667 and 668:

Table 1: Responses from 10 Subject

- Page 669 and 670:

Table 3: Regression for FFM on Tran

- Page 671 and 672:

comprehensive guide that the Army c

- Page 673 and 674:

FRAMEWORK COMPARISON: 1958; 1973; 1

- Page 675 and 676:

Our review of the evolution of the

- Page 677 and 678:

DEVELOPING APPROPRIATE METRICS FOR

- Page 679 and 680:

METHOD Participants Participants we

- Page 681 and 682:

RESULTS Results are broken out belo

- Page 683 and 684:

As depicted in Table 3, half of par

- Page 685 and 686:

Table 5. Second Choice Rating Forma

- Page 687 and 688:

SOFTWARE SUPPORT OF HUMAN PERFORMAN

- Page 689 and 690:

SOFTWARE SUPPORT A working model (p

- Page 691 and 692:

Figure 3, illustrates the prototype

- Page 693 and 694:

framework. Having completed the ver

- Page 695 and 696:

HOW MILITARY RESEARCH CAN IMPROVE T

- Page 697 and 698:

characteristics” - such as task c

- Page 699 and 700:

Team-Coordination Training Another

- Page 701 and 702:

Numerous lessons learned have come

- Page 703 and 704:

teamwork training: Evaluation resul

- Page 705 and 706:

participated in informal class exer

- Page 707 and 708:

slightly modified for the second wo

- Page 709 and 710:

As a result, we are currently devel

- Page 711 and 712:

It was not surprising that decoloni

- Page 713 and 714:

a conflict. The end of the cold war

- Page 715 and 716:

understanding. Also, when individua

- Page 717 and 718:

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE (1996). White

- Page 719 and 720:

. Screening and monitoring of perso

- Page 721 and 722:

The TSES-R is a 13 item scale of po

- Page 723 and 724:

Career Intention Prior to Deploymen

- Page 725 and 726:

d. The sample is based on peace ope

- Page 727 and 728:

comparing self- and subordinate des

- Page 729 and 730:

5 4 3 2 1 Figure 1 - Mean Perceptio

- Page 731 and 732:

0.9 0.7 0.5 0.3 0.1 -0.1 Figure 2 -

- Page 733 and 734:

adding another variable of individu

- Page 735 and 736:

REFERENCES Baranski, J.V., & Petrus

- Page 737 and 738:

Leadership Competencies: Are We All

- Page 739 and 740:

The purpose in establishing compete

- Page 741 and 742:

Army - influencing people - by prov

- Page 743 and 744:

Table 3 Leadership Competency Compo

- Page 745 and 746:

In answer to ‘are we all saying t

- Page 747 and 748:

Navy Decisiveness /Risk Management

- Page 749 and 750:

Marine Corps Leadership Principles

- Page 751 and 752:

All potential military recruits mus

- Page 753 and 754:

successful completion of basic lang

- Page 755 and 756:

investigate whether it or a similar

- Page 757 and 758:

• NEXT STEPS As a first priority,

- Page 759 and 760:

INTRODUCTION This study investigate

- Page 761 and 762:

Table 2. Summary Goodness of Fit in

- Page 763 and 764:

Analysis of the 18-item Scale DISCU

- Page 765 and 766:

Lim, B. (2001). The Structure and N

- Page 767 and 768:

NSmen’s training cycle last for t

- Page 769 and 770:

To test the robustness of the hypot

- Page 771 and 772:

Table 2.3. Scale Reliabilities and

- Page 773 and 774:

Figure 3: Model for Regulars *0.57

- Page 775 and 776:

REFERENCES Huxley, T. (2000). Defen

- Page 777 and 778:

Another important influence on our

- Page 779 and 780:

as a multidimensional construct. Ta

- Page 781 and 782:

Table 3 Intercorrelations Among Pro

- Page 783 and 784:

METHOD PARTICIPANTS The DEOCS had b

- Page 785 and 786:

There is a link between test constr

- Page 787 and 788:

Truhon, S. A. (1999). Updating the

- Page 789 and 790:

attitudes and behaviors observed an

- Page 791 and 792:

effective way to re-build survivors

- Page 793 and 794:

Reference List Bunker, K.A. (1997).

- Page 795 and 796:

VALIDATION OF THE BELGIAN MILITARY

- Page 797 and 798:

instructions, in order to make obse

- Page 799 and 800:

Interviews GFD dichotomous was regr

- Page 801 and 802:

784 INDEX OF AUTHORS Acromite, M. 7

- Page 803:

786 INDEX OF AUTHORS Waugh, G.W. 54