Gibson Ferguson Language Planning and Education Edinburgh ...

Gibson Ferguson Language Planning and Education Edinburgh ...

Gibson Ferguson Language Planning and Education Edinburgh ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

86 <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

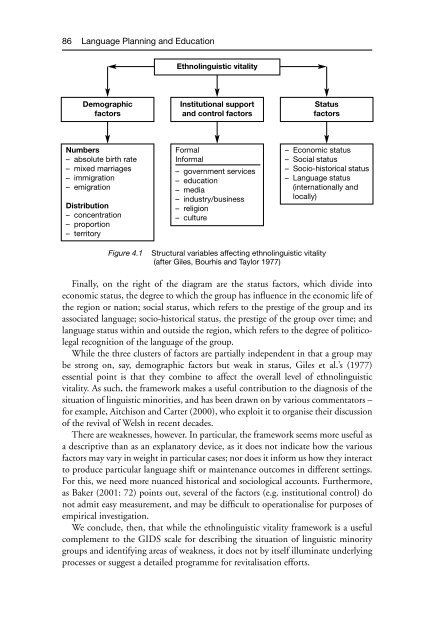

Demographic<br />

factors<br />

Numbers<br />

– absolute birth rate<br />

– mixed marriages<br />

– immigration<br />

– emigration<br />

Distribution<br />

– concentration<br />

– proportion<br />

– territory<br />

Ethnolinguistic vitality<br />

Institutional support<br />

<strong>and</strong> control factors<br />

Formal<br />

Informal<br />

– government services<br />

– education<br />

– media<br />

– industry/business<br />

– religion<br />

– culture<br />

Figure 4.1 Structural variables affecting ethnolinguistic vitality<br />

(after Giles, Bourhis <strong>and</strong> Taylor 1977)<br />

Status<br />

factors<br />

– Economic status<br />

– Social status<br />

– Socio-historical status<br />

– <strong>Language</strong> status<br />

(internationally <strong>and</strong><br />

locally)<br />

Finally, on the right of the diagram are the status factors, which divide into<br />

economic status, the degree to which the group has influence in the economic life of<br />

the region or nation; social status, which refers to the prestige of the group <strong>and</strong> its<br />

associated language; socio-historical status, the prestige of the group over time; <strong>and</strong><br />

language status within <strong>and</strong> outside the region, which refers to the degree of politicolegal<br />

recognition of the language of the group.<br />

While the three clusters of factors are partially independent in that a group may<br />

be strong on, say, demographic factors but weak in status, Giles et al.’s (1977)<br />

essential point is that they combine to affect the overall level of ethnolinguistic<br />

vitality. As such, the framework makes a useful contribution to the diagnosis of the<br />

situation of linguistic minorities, <strong>and</strong> has been drawn on by various commentators –<br />

for example, Aitchison <strong>and</strong> Carter (2000), who exploit it to organise their discussion<br />

of the revival of Welsh in recent decades.<br />

There are weaknesses, however. In particular, the framework seems more useful as<br />

a descriptive than as an explanatory device, as it does not indicate how the various<br />

factors may vary in weight in particular cases; nor does it inform us how they interact<br />

to produce particular language shift or maintenance outcomes in different settings.<br />

For this, we need more nuanced historical <strong>and</strong> sociological accounts. Furthermore,<br />

as Baker (2001: 72) points out, several of the factors (e.g. institutional control) do<br />

not admit easy measurement, <strong>and</strong> may be difficult to operationalise for purposes of<br />

empirical investigation.<br />

We conclude, then, that while the ethnolinguistic vitality framework is a useful<br />

complement to the GIDS scale for describing the situation of linguistic minority<br />

groups <strong>and</strong> identifying areas of weakness, it does not by itself illuminate underlying<br />

processes or suggest a detailed programme for revitalisation efforts.