sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Energy Intensive Industries<br />

intensive sector or the electricity sector meet a hard reduction target, with no trading across the<br />

economy, still implies that reductions are made in a cost-effective manner within the sector. We<br />

expect that technology st<strong>and</strong>ards or hard targets prescribed on a plant-by-plant or firm-by-firm<br />

basis, without inter-sector trade, would lead to greater inefficiency <strong>and</strong> higher <strong>economic</strong> cost than<br />

we estimate.<br />

Our cost estimates must be qualified if there are pre-existing <strong>economic</strong> distortions that are<br />

“corrected” by the carbon policy, even though the policy itself may appear to be inefficient.<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> such a pre-existing distortions include high excise taxes on electricity (Babiker,<br />

Reilly, <strong>and</strong> Ellerman, 1999), or on refined fuels (Babiker, Reilly <strong>and</strong> Jacoby, 2000). Also, our<br />

estimates do not account for possible <strong>benefits</strong>, such as equity concerns, aid for depressed areas,<br />

or ancillary environmental <strong>benefits</strong> that may help justify the choice <strong>of</strong> these sector-specific<br />

measures. However, even taking these qualifying factors into account, we believe that, given the<br />

level <strong>of</strong> aggregation applied in this study, our results will tend to understate the welfare effects <strong>of</strong><br />

differentiating emissions controls by sector, <strong>and</strong> may miss some <strong>of</strong> the shifts <strong>of</strong> activity among<br />

sectors <strong>and</strong> unintended effects on sector trade balances. 1<br />

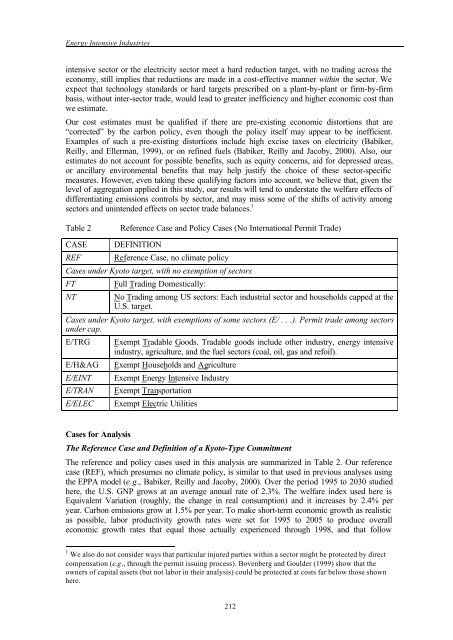

Table 2<br />

Reference Case <strong>and</strong> Policy Cases (No International Permit Trade)<br />

CASE<br />

REF<br />

DEFINITION<br />

Reference Case, no climate policy<br />

Cases under Kyoto target, with no exemption <strong>of</strong> sectors<br />

FT<br />

NT<br />

Full Trading Domestically:<br />

No Trading among US sectors: Each industrial sector <strong>and</strong> households capped at the<br />

U.S. target.<br />

Cases under Kyoto target, with exemptions <strong>of</strong> some sectors (E/ . . .). Permit trade among sectors<br />

under cap.<br />

E/TRG<br />

E/H&AG<br />

E/EINT<br />

E/TRAN<br />

E/ELEC<br />

Exempt Tradable Goods. Tradable goods include other industry, energy intensive<br />

industry, agriculture, <strong>and</strong> the fuel sectors (coal, oil, gas <strong>and</strong> refoil).<br />

Exempt Households <strong>and</strong> Agriculture<br />

Exempt Energy Intensive Industry<br />

Exempt Transportation<br />

Exempt Electric Utilities<br />

Cases for Analysis<br />

The Reference Case <strong>and</strong> Definition <strong>of</strong> a Kyoto-Type Commitment<br />

The reference <strong>and</strong> policy cases used in this analysis are summarized in Table 2. Our reference<br />

case (REF), which presumes no climate policy, is similar to that used in previous analyses using<br />

the EPPA model (e.g., Babiker, Reilly <strong>and</strong> Jacoby, 2000). Over the period 1995 to 2030 studied<br />

here, the U.S. GNP grows at an average annual rate <strong>of</strong> 2.3%. The welfare index used here is<br />

Equivalent Variation (roughly, the change in real consumption) <strong>and</strong> it increases by 2.4% per<br />

year. Carbon emissions grow at 1.5% per year. To make short-term <strong>economic</strong> growth as realistic<br />

as possible, labor productivity growth rates were set for 1995 to 2005 to produce overall<br />

<strong>economic</strong> growth rates that equal those actually experienced through 1998, <strong>and</strong> that follow<br />

1 We also do not consider ways that particular injured parties within a sector might be protected by direct<br />

compensation (e.g., through the permit issuing process). Bovenberg <strong>and</strong> Goulder (1999) show that the<br />

owners <strong>of</strong> capital assets (but not labor in their analysis) could be protected at <strong>costs</strong> far below those shown<br />

here.<br />

212