sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

sectoral economic costs and benefits of ghg mitigation - IPCC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Seth Dunn <strong>and</strong> Michael Renner<br />

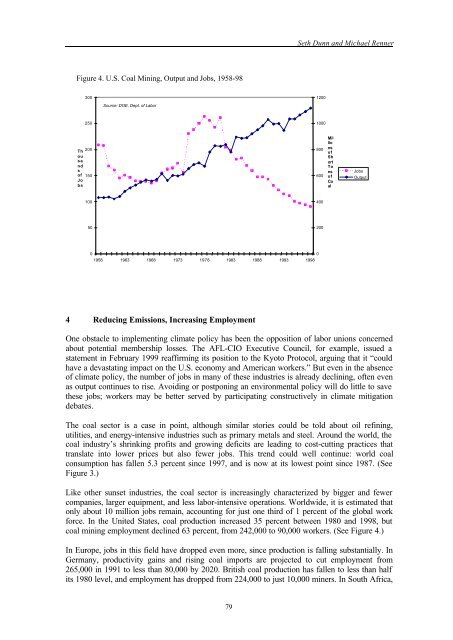

Figure 4. U.S. Coal Mining, Output <strong>and</strong> Jobs, 1958-98<br />

300<br />

Source: DOE, Dept. <strong>of</strong> Labor<br />

1200<br />

250<br />

1000<br />

Th<br />

ou<br />

sa<br />

nd<br />

s<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

Jo<br />

bs<br />

200<br />

150<br />

800<br />

600<br />

Mil<br />

lio<br />

ns<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

Sh<br />

ort<br />

To<br />

ns<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

Co<br />

al<br />

Jobs<br />

Output<br />

100<br />

400<br />

50<br />

200<br />

0<br />

1958 1963 1968 1973 1978 1983 1988 1993 1998<br />

0<br />

4 Reducing Emissions, Increasing Employment<br />

One obstacle to implementing climate policy has been the opposition <strong>of</strong> labor unions concerned<br />

about potential membership losses. The AFL-CIO Executive Council, for example, issued a<br />

statement in February 1999 reaffirming its position to the Kyoto Protocol, arguing that it “could<br />

have a devastating impact on the U.S. economy <strong>and</strong> American workers.” But even in the absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> climate policy, the number <strong>of</strong> jobs in many <strong>of</strong> these industries is already declining, <strong>of</strong>ten even<br />

as output continues to rise. Avoiding or postponing an environmental policy will do little to save<br />

these jobs; workers may be better served by participating constructively in climate <strong>mitigation</strong><br />

debates.<br />

The coal sector is a case in point, although similar stories could be told about oil refining,<br />

utilities, <strong>and</strong> energy-intensive industries such as primary metals <strong>and</strong> steel. Around the world, the<br />

coal industry’s shrinking pr<strong>of</strong>its <strong>and</strong> growing deficits are leading to cost-cutting practices that<br />

translate into lower prices but also fewer jobs. This trend could well continue: world coal<br />

consumption has fallen 5.3 percent since 1997, <strong>and</strong> is now at its lowest point since 1987. (See<br />

Figure 3.)<br />

Like other sunset industries, the coal sector is increasingly characterized by bigger <strong>and</strong> fewer<br />

companies, larger equipment, <strong>and</strong> less labor-intensive operations. Worldwide, it is estimated that<br />

only about 10 million jobs remain, accounting for just one third <strong>of</strong> 1 percent <strong>of</strong> the global work<br />

force. In the United States, coal production increased 35 percent between 1980 <strong>and</strong> 1998, but<br />

coal mining employment declined 63 percent, from 242,000 to 90,000 workers. (See Figure 4.)<br />

In Europe, jobs in this field have dropped even more, since production is falling substantially. In<br />

Germany, productivity gains <strong>and</strong> rising coal imports are projected to cut employment from<br />

265,000 in 1991 to less than 80,000 by 2020. British coal production has fallen to less than half<br />

its 1980 level, <strong>and</strong> employment has dropped from 224,000 to just 10,000 miners. In South Africa,<br />

79