Biomechanics and Medicine in Swimming XI

Biomechanics and Medicine in Swimming XI

Biomechanics and Medicine in Swimming XI

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

There was no significant difference <strong>in</strong> swimm<strong>in</strong>g velocity between IT6*500 <strong>and</strong> IT30*100<br />

for each 500 m. Expressed <strong>in</strong> % v 2 O V& max <strong>and</strong> % vLT, swimm<strong>in</strong>g velocities were 96.4 ±<br />

3.4 <strong>and</strong> 99.2 ± 3.6% for IT6*500 <strong>and</strong> 96.7 ± 3.4 <strong>and</strong> 99.4 ± 4.4% for IT30*100 respectively.<br />

Although the swimm<strong>in</strong>g velocity was similar dur<strong>in</strong>g IT6*500 <strong>and</strong> IT30*100, VO2 & mean,<br />

VE & mean, BL <strong>and</strong> RPE were greater for IT6*500 than IT30*100 (63.8±3.9 vs. 57.3±3.1<br />

mL.kg -1 ·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ; 79.6±18.8 vs. 73.2±10.5 mL·kg -1 ·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ; 4.1±1.2 vs. 3.2±1.4 mmol·L -1 ;<br />

17.3±2.4 vs. 14.7±3.1 a.u. P < 0.05). T>90% was greater for IT6*500 (1357 ± 288 vs. 562<br />

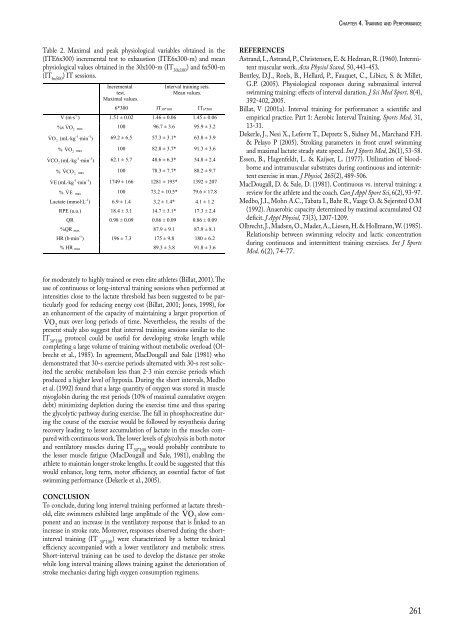

Table 2. Maximal <strong>and</strong> peak physiological variables obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

(ITE6x300) ± 326 s, P < 0.05) <strong>in</strong>cremental (Table 2). test to exhaustion (ITE6x300-m) <strong>and</strong> mean<br />

physiological values obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the 30x100-m (IT30x100 ) <strong>and</strong> 6x500-m<br />

(IT6x500 ) IT sessions.<br />

Table 2. Maximal <strong>and</strong> peak physiological variables obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the (ITE6x300)<br />

<strong>in</strong>cremental test to exhaustion (ITE6x300-m) <strong>and</strong> mean physiological values obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><br />

the 30x100-m (IT30x100) <strong>and</strong> 6x500-m (IT6x500) IT sessions.<br />

Incremental<br />

Interval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sets.<br />

test.<br />

Mean values.<br />

Maximal values.<br />

6*300 IT30*100 IT6*500<br />

V (m·s -1 ) 1.51 ± 0.02 1.46 ± 0.06 1.45 ± 0.06<br />

%v 2 O V& max 100 96.7 ± 3.6 95.9 ± 3.2<br />

VO 2<br />

& (mL·kg -1 ·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ) 69.2 ± 6.5 57.3 ± 3.1* 63.8 ± 3.9<br />

% VO2 & max 100 82.8 ± 3.7* 91.3 ± 3.6<br />

VCO2 & (mL·kg -1 ·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ) 62.1 ± 5.7 48.6 ± 6.3* 54.8 ± 2.4<br />

% VCO2 & max 100 78.3 ± 7.7* 88.2 ± 9.7<br />

VE & (mL·kg -1 ·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ) 1749 ± 166 1281 ± 193* 1392 ± 207<br />

% VE & max 100 73.2 ± 10.5* 79.6 ± 17.8<br />

Lactate (mmol·L -1 ) 6.9 ± 1.4 3.2 ± 1.4* 4.1 ± 1.2<br />

RPE (a.u.) 18.4 ± 3.1 14.7 ± 3.1* 17.3 ± 2.4<br />

QR 0.98 ± 0.09 0.86 ± 0.09 0.86 ± 0.09<br />

%QR max 87.9 ± 9.1 87.9 ± 8.1<br />

HR (b·m<strong>in</strong> -1 ) 196 ± 7.3 175 ± 9.8 180 ± 6.2<br />

% HR max 89.3 ± 3.8 91.8 ± 3.6<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

The major f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of this study is that the long <strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g set (IT6*500m) which was<br />

performed at vLT displayed higher physiological responses <strong>and</strong> longer time susta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

above 90% VO2 & for moderately to highly tra<strong>in</strong>ed or even elite athletes (Billat, 2001). The<br />

use of cont<strong>in</strong>uous max compared or long-<strong>in</strong>terval with the shorter tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terval sessions tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g when (IT30*100m). performed This at is <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tensities close to the lactate threshold has been suggested to be particularly<br />

good for reduc<strong>in</strong>g energy cost (Billat, 2001; Jones, 1998), for<br />

an enhancement of the capacity of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a larger proportion of<br />

VO � max over long periods of time. Nevertheless, the results of the<br />

2<br />

present study also suggest that <strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sessions similar to the<br />

IT 30*100 protocol could be useful for develop<strong>in</strong>g stroke length while<br />

complet<strong>in</strong>g a large volume of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g without metabolic overload (Olbrecht<br />

et al., 1985). In agreement, MacDougall <strong>and</strong> Sale (1981) who<br />

demonstrated that 30-s exercise periods alternated with 30-s rest solicited<br />

the aerobic metabolism less than 2-3 m<strong>in</strong> exercise periods which<br />

produced a higher level of hypoxia. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the short <strong>in</strong>tervals, Medbo<br />

et al. (1992) found that a large quantity of oxygen was stored <strong>in</strong> muscle<br />

myoglob<strong>in</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the rest periods (10% of maximal cumulative oxygen<br />

debt) m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g depletion dur<strong>in</strong>g the exercise time <strong>and</strong> thus spar<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the glycolytic pathway dur<strong>in</strong>g exercise. The fall <strong>in</strong> phosphocreat<strong>in</strong>e dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the course of the exercise would be followed by resynthesis dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

recovery lead<strong>in</strong>g to lesser accumulation of lactate <strong>in</strong> the muscles compared<br />

with cont<strong>in</strong>uous work. The lower levels of glycolysis <strong>in</strong> both motor<br />

<strong>and</strong> ventilatory muscles dur<strong>in</strong>g IT 30*100 would probably contribute to<br />

the lesser muscle fatigue (MacDougall <strong>and</strong> Sale, 1981), enabl<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

athlete to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> longer stroke lengths. It could be suggested that this<br />

would enhance, long term, motor efficiency, an essential factor of fast<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g performance (Dekerle et al., 2005).<br />

conclusIon<br />

To conclude, dur<strong>in</strong>g long <strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g performed at lactate threshold,<br />

elite swimmers exhibited large amplitude of the 2 O V� slow component<br />

<strong>and</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the ventilatory response that is l<strong>in</strong>ked to an<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> stroke rate. Moreover, responses observed dur<strong>in</strong>g the short<strong>in</strong>terval<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (IT 30*100 ) were characterized by a better technical<br />

efficiency accompanied with a lower ventilatory <strong>and</strong> metabolic stress.<br />

Short-<strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g can be used to develop the distance per stroke<br />

while long <strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g allows tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the deterioration of<br />

stroke mechanics dur<strong>in</strong>g high oxygen consumption regimens.<br />

chaPter4.tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong>Performance<br />

reFerences<br />

Astr<strong>and</strong>, I., Astr<strong>and</strong>, P., Christensen, E. & Hedman, R. (1960). Intermitent<br />

muscular work. Acta Physiol Sc<strong>and</strong>, 50, 443-453.<br />

Bentley, D.J., Roels, B., Hellard, P., Fauquet, C., Libicz, S. & Millet,<br />

G.P. (2005). Physiological responses dur<strong>in</strong>g submaximal <strong>in</strong>terval<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g: effects of <strong>in</strong>terval duration. J Sci Med Sport, 8(4),<br />

392-402, 2005.<br />

Billat, V (2001a). Interval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for performance: a scientific <strong>and</strong><br />

empirical practice. Part 1: Aerobic Interval Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Sports Med, 31,<br />

13-31.<br />

Dekerle, J., Nesi X., Lefevre T., Depretz S., Sidney M., March<strong>and</strong> F.H.<br />

& Pelayo P (2005). Strok<strong>in</strong>g parameters <strong>in</strong> front crawl swimm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> maximal lactate steady state speed. Int J Sports Med, 26(1), 53-58.<br />

Essen, B., Hagenfeldt, L. & Kaijser, L. (1977). Utilization of bloodborne<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tramuscular substrates dur<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>termittent<br />

exercise <strong>in</strong> man. J Physiol, 265(2), 489-506.<br />

MacDougall, D. & Sale, D. (1981). Cont<strong>in</strong>uous vs. <strong>in</strong>terval tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g: a<br />

review for the athlete <strong>and</strong> the coach. Can J Appl Sport Sci, 6(2), 93-97.<br />

Medbo, J.I., Mohn A.C., Tabata I., Bahr R., Vaage O. & Sejersted O.M<br />

(1992). Anaerobic capacity determ<strong>in</strong>ed by maximal accumulated O2<br />

deficit. J Appl Physiol, 73(3), 1207-1209.<br />

Olbrecht, J., Madsen, O., Mader, A., Liesen, H. & Hollmann, W. (1985).<br />

Relationship between swimm<strong>in</strong>g velocity <strong>and</strong> lactic concentration<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>termittent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g exercises. Int J Sports<br />

Med, 6(2), 74-77.<br />

261