- Page 3: THE GENRE OF TROLLS

- Page 7 and 8: THE GENRE OF TROLLS The Case of a F

- Page 9 and 10: PREFACE I have greatly enjoyed writ

- Page 11 and 12: colleagues to obtain much of my res

- Page 13 and 14: TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface vii 1 Int

- Page 15: 6.4 Novelization 248 6.5 Integratin

- Page 18 and 19: well. Finally, “3.4 Breaking the

- Page 20 and 21: conception of the troll. 1 The obje

- Page 22 and 23: the tension and interplay between t

- Page 24 and 25: are the same as those of the concep

- Page 26 and 27: the practice of changing babies; he

- Page 28 and 29: orientation of the speaker to the r

- Page 30 and 31: and vivid, while the troll in fairy

- Page 32 and 33: Holbek broaches a subject that will

- Page 34 and 35: make a similar, more extended and s

- Page 36 and 37: such as trolls, jötnar and other b

- Page 38 and 39: one other text can be read (Kristev

- Page 40 and 41: vocabulary of intertextual theory,

- Page 44 and 45: various formulations of a theme hav

- Page 46 and 47: constitutes an intertextual network

- Page 48 and 49: of them are not even texts, they ma

- Page 50 and 51: Lotte Tarkka implicitly modelled he

- Page 52 and 53: Laura Stark-Arola’s account of th

- Page 54 and 55: disparate material constituted by t

- Page 56 and 57: so Barthes claims. Nevertheless, Ba

- Page 58 and 59: 1.5 Method The choice of material h

- Page 60 and 61: in stories of the supernatural has

- Page 62 and 63: 2 MATERIAL AND CONTEXT 2.1 General

- Page 64 and 65: Rancken tried to entice his pupils

- Page 66 and 67: made in the parish of Vörå. One g

- Page 68 and 69: collection was entrusted to kompete

- Page 70 and 71: narrator’s train of thoughts cann

- Page 72 and 73: 56 Vöråbon är förbehållsam, re

- Page 74 and 75: 58 Vid antecknandet af traditionen

- Page 76 and 77: entitled “En jägares äfventyr

- Page 78 and 79: the verge of a civil war, he travel

- Page 80 and 81: 64 och således misstron mot främl

- Page 82 and 83: There are four narratives in these

- Page 84 and 85: Edvard Wefvar, who collected in Nyl

- Page 86 and 87: 70 pärlor, värda att hopsamlas oc

- Page 88 and 89: villages: the villages of Rejpelt,

- Page 90 and 91: 331; Åkerblom 1963: 301); as menti

- Page 92 and 93:

2.3.2 Religious context One of my p

- Page 94 and 95:

started giving Bible classes in the

- Page 96 and 97:

e made in this context; firstly, th

- Page 98 and 99:

for shorter periods. He represented

- Page 100 and 101:

in Russia is said to presage the ou

- Page 102 and 103:

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE TROLL TRADITIO

- Page 104 and 105:

conducive to an encounter with trol

- Page 106 and 107:

28, 12). As Inger Lövkrona has poi

- Page 108 and 109:

In one story, the troll comes to th

- Page 110 and 111:

the unhappy troll to its present ha

- Page 112 and 113:

with their beautiful singing and po

- Page 114 and 115:

An old troll sports a wand possessi

- Page 116 and 117:

to intrude on the wedding and save

- Page 118 and 119:

when he was allowed to go to church

- Page 120 and 121:

104 do it. Butterbelly was going to

- Page 122 and 123:

3.3.2 Tension-Filled Tolerance Man

- Page 124 and 125:

on similar motifs as an expression

- Page 126 and 127:

110 Jag har av gammalt folk hört e

- Page 128 and 129:

which the father of the child is so

- Page 130 and 131:

the impertinence of its human frien

- Page 132 and 133:

true to its word. The troll will sa

- Page 134 and 135:

to return to his cows. The shepherd

- Page 136 and 137:

Some texts merely comment on the di

- Page 138 and 139:

is complete when the man and his wa

- Page 140 and 141:

sacred text, which belongs to the c

- Page 142 and 143:

1887, 19), and a lion must dance th

- Page 144 and 145:

128 Later when the troll was away,

- Page 146 and 147:

children or banishing trolls from t

- Page 148 and 149:

y Bolstad Skjelbred, and she regard

- Page 150 and 151:

After drinking the water of the oth

- Page 152 and 153:

etween the sexes and age groups. Th

- Page 154 and 155:

destinataire (ou du personnage), du

- Page 156 and 157:

inherent in the text relieves these

- Page 158 and 159:

word or phrase employed instead of

- Page 160 and 161:

144 1) Bergtrollen sägas gärna lo

- Page 162 and 163:

pronounces the benediction. In this

- Page 164 and 165:

Little Maja refuses to confess her

- Page 166 and 167:

unaware of the hardships constituti

- Page 168 and 169:

The theme of vanity recurs here, bu

- Page 170 and 171:

The image of blindness, concrete in

- Page 172 and 173:

156 Så war uti Damasco en lärjung

- Page 174 and 175:

158 13) in ánnan påjk råka två

- Page 176 and 177:

to the everyday world in the manner

- Page 178 and 179:

162 Wår egen kraft är här för s

- Page 180 and 181:

The everyday world - application of

- Page 182 and 183:

marked. It is a reversion of Saul

- Page 184 and 185:

168 guldur. Då husbonden såg penn

- Page 186 and 187:

The primeval apple mingles with the

- Page 188 and 189:

his father-in-law against him, Jaco

- Page 190 and 191:

And when he had spent all, there ar

- Page 192 and 193:

176 öfwer henne. Då talade Cain m

- Page 194 and 195:

28) Öppna mig förståndets öga,

- Page 196 and 197:

of a paradisical state on earth (te

- Page 198 and 199:

182 Later on two Thursday mornings

- Page 200 and 201:

ather the other way around; on this

- Page 202 and 203:

other girls are simply too virtuous

- Page 204 and 205:

the intertwining of various interte

- Page 206 and 207:

Who had his dwelling among the tomb

- Page 208 and 209:

192 10) In those days when there we

- Page 210 and 211:

194 spin the hat and ask: ‘Isn’

- Page 212 and 213:

196 will stop and pee at the same t

- Page 214 and 215:

And the princes, governors, and cap

- Page 216 and 217:

And when she hath found it, she cal

- Page 218 and 219:

202 19) Jungfru Lena satt på Kelle

- Page 220 and 221:

20) Then cometh he to a city in Sam

- Page 222 and 223:

And he denied it again. And a littl

- Page 224 and 225:

considerable power over his parishi

- Page 226 and 227:

y regulated practices (senses two a

- Page 228 and 229:

this reluctance demonstrates that d

- Page 230 and 231:

same was suggested in the case of t

- Page 232 and 233:

epresentation, embodied in the imag

- Page 234 and 235:

6 GENRE, PARODY, CHRONOTOPES AND NO

- Page 236 and 237:

ounded texts with strong social and

- Page 238 and 239:

gap, minimization and maximization,

- Page 240 and 241:

of many tales (Propp 1970: 99), and

- Page 242 and 243:

defies the traditional wisdom artic

- Page 244 and 245:

228 2) Little Matt Once a workingma

- Page 246 and 247:

was married to the eldest and after

- Page 248 and 249:

world. His friends are deceitful, h

- Page 250 and 251:

indicates that the material used in

- Page 252 and 253:

discourse she is an equally enthral

- Page 254 and 255:

238 svar éli se dem. tå an ha gai

- Page 256 and 257:

240 rummet, stodo utmed dörren ett

- Page 258 and 259:

242 under the bed. The boy was look

- Page 260 and 261:

listener’s or reader’s expectat

- Page 262 and 263:

synchronous (cf. Bakhtin 1986b: 28,

- Page 264 and 265:

that he has subverted the ethical f

- Page 266 and 267:

stressed in his early works (Bakhti

- Page 268 and 269:

collectors, and maybe of his local

- Page 270 and 271:

the anxieties of the latter, even t

- Page 272 and 273:

In this theory of aesthetic activit

- Page 274 and 275:

Here Bakhtin describes perception i

- Page 276 and 277:

Bakhtin, the gift of form requires

- Page 278 and 279:

all the lies and silences passing b

- Page 280 and 281:

creation of aesthetic love. Firstly

- Page 282 and 283:

When the troll arrives to extend th

- Page 284 and 285:

its chosen form exacerbates its unf

- Page 286 and 287:

270 den så grann?” - “Nå, nä

- Page 288 and 289:

ecause death seldom furnishes a fin

- Page 290 and 291:

7.4 Aborted Dialogues A rather spec

- Page 292 and 293:

ization and unfinalizability co-exi

- Page 294 and 295:

absolutely necessary ingredient. Ob

- Page 296 and 297:

8 DISCUSSION In this dissertation I

- Page 298 and 299:

mentalities; in spite of the social

- Page 300 and 301:

exhibited the Bakhtinian form of di

- Page 302 and 303:

9 ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY AT

- Page 304 and 305:

Bakhtin, M. M. 1993: Toward a Philo

- Page 306 and 307:

Dentith, Simon 1995: Bakhtinian Tho

- Page 308 and 309:

Hartmann, Elisabeth 1936: Die Troll

- Page 310 and 311:

Hymes, Dell 1989: Ways of Speaking.

- Page 312 and 313:

Mills, Sara 2002: Discourse. Routle

- Page 314 and 315:

Siikala, Anna-Leena 2000b: Variatio

- Page 316 and 317:

Vice, Sue 1997: Introducing Bakhtin

- Page 318 and 319:

R II 131: Löpargossen och hans kat

- Page 320 and 321:

3) Tsjittargrå He va’ ejngang e

- Page 322 and 323:

yet”, the bear answered. When the

- Page 324 and 325:

i sama unjiform, som ’an va i, to

- Page 326 and 327:

10) The Three Suitors Once upon a t

- Page 328 and 329:

Kaptejnin fréga’ to, om dem int

- Page 330 and 331:

the midnight sun. Her husband didn

- Page 332 and 333:

5) Vanligtvis hålla sig trollen i

- Page 334 and 335:

gick tå å sa åt bondn, hä a sku

- Page 336 and 337:

Eve and come there among the trolls

- Page 338 and 339:

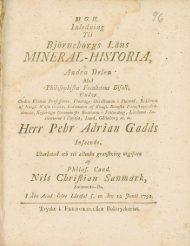

Fig. 2. The banishment of Adam and

- Page 340 and 341:

Fig. 4. The Prodigal Son (Luke 15:2

- Page 342 and 343:

Fig. 6. Peter denies Christ (Luke 2

- Page 344:

Fig. 8. The conversion of Paul on t