Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CHAPTER 2<br />

CENTRAL OHIO VALLEY DURING THE LATE PREHISTORIC PERIOD:<br />

<strong>Subsistence</strong>-<strong>Settlement</strong> Systems’ Responses to Risk<br />

Flora Church and John P. Nass, Jr.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Central Ohio Valley Late Prehistoric societies<br />

referred to as Fort Ancient (Figure 2.1) responded to<br />

environmental and social perturbations associated<br />

with maize farming, population growth, sedentism,<br />

and population aggregation through changes in settlement<br />

arrangement and social organization. The effects<br />

of these choices and population growth upon settlement<br />

and subsistence systems are evaluated in this<br />

chapter by examining changes within the social, economic,<br />

and technological spheres over time. In the<br />

interval of time ca. A.D. 900/1000 to A.D. 1400, several<br />

Late Prehistoric cultural phases have been identified<br />

throughout the central Ohio Valley. Within this roughly<br />

400-year interval, the Feurt, Baum, Anderson,<br />

Osborne, Manion, and Crogham phases of the Fort<br />

Ancient Tradition have been identified (Figure 2.2)<br />

(Griffin 1943; Henderson and Turnbow 1987; Turnbow<br />

and Sharp 1988). Also, Cowan (1986) has described the<br />

Turpin, Shoemaker, and Campbell Island phases within<br />

the lower Great and Little Miami drainages in<br />

southwestern Ohio, while Carskadden and Morton<br />

(1977, 2000) have made a case for the Philo phase in<br />

eastern Ohio (Figure 2.3). These Late Prehistoric phases<br />

differ substantially from the preceding Late<br />

Woodland cultural base (Church 1987; Graybill 1981;<br />

Wagner 1987). Data from a number of central Ohio<br />

Valley Late Woodland sites (Figure 2.4) will also be<br />

used to contrast with the changes documented at Late<br />

Prehistoric sites. We end our study at ca. A.D. 1400,<br />

when the regional variation (denoted by the various<br />

phases) becomes subsumed within a central Ohio<br />

Valley-wide ceramic style zone referred to as the<br />

Madisonville Horizon (Henderson et al. 1992).<br />

Accompanying this ceramic zone is a gravitation of<br />

settlements toward the Ohio River proper and the<br />

lower reaches of its major tributaries.<br />

THEORETICAL ISSUES<br />

The spatial distribution of human populations can<br />

be arranged in a continuum from dispersed to nucleated.<br />

A dispersed population does not occur in<br />

clumps, but is more evenly arranged across the landscape<br />

in smaller units in relation to its resource base.<br />

At the other extreme, a nucleated or aggregated population<br />

resides in larger units that tend to reside at<br />

fixed locations for long periods of time. For this reason,<br />

large populations place greater demands on the<br />

local resource base. Long-term nucleation can result<br />

from a number of factors, such as defense against<br />

resource encroachment, or a need for pooling labor to<br />

facilitate resource procurement, or when resource<br />

productivity exceeds immediate needs and energy<br />

expenditure (Dancey 1992; Fuller 1981; Harris 1989).<br />

Whatever the arrangement of populations and the<br />

technology and buffering methods developed, labor<br />

is organized to ensure a continued supply of<br />

resources, be they collected, hunted, or grown.<br />

Leonard and Reed (1993:651) refer to the logistics of<br />

resource procurement as “strategies” and “tactics.”<br />

Strategies refer to what resources are to be procured or<br />

grown and in what quantities, while tactics refer to the<br />

methods (the organization of labor, social arrangement,<br />

etc.) used to obtain the desired resources. As both local<br />

and regional populations increase and seasonal mobility<br />

as a means of mitigating overexploitation is<br />

reduced, populations will be forced to devise tactics<br />

(which could include buffering mechanisms such as<br />

storage and/or exchange) to ensure a constant supply<br />

of needed resources (Braun and Plog 1982). Leonard<br />

and Reed (1993:651-652) contend those tactics and<br />

buffering mechanisms that are more successful at<br />

maintaining the necessary types and quantities of<br />

dietary staples (which increases the relative fitness or<br />

reproductive success of individuals within the<br />

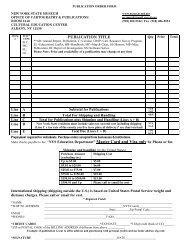

<strong>Northeast</strong> <strong>Subsistence</strong>-<strong>Settlement</strong> <strong>Change</strong>: A.D. <strong>700</strong><strong>–1300</strong> by John P. Hart and Christina B. Rieth. New York State Museum<br />

© 2002 by the University of the State of New York, The State Education Department, Albany, New York. All rights reserved.<br />

Chapter 2 Central Ohio Valley During the Late Prehistoric Period: Subsistance-<strong>Settlement</strong> Systems’ Responses to Risk 11