- Page 1 and 2:

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Ch

- Page 3 and 4:

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Ch

- Page 5 and 6:

TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures L

- Page 7 and 8:

LIST OF FIGURES 2.1 Map of the cent

- Page 9 and 10:

9.3 Topographic map of Broome Tech.

- Page 11 and 12:

11.1 Upper Susquehanna Site Types (

- Page 13 and 14: PREFACE The New York State Museum h

- Page 15 and 16: CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Christina B.

- Page 17 and 18: domesticates and the occupation of

- Page 19 and 20: and Rieth highlight the important c

- Page 21 and 22: Dunnell, R. C. (1971). Systematics

- Page 23 and 24: Anthropology, University of Massach

- Page 25 and 26: CHAPTER 2 CENTRAL OHIO VALLEY DURIN

- Page 27 and 28: L a k e E r i e PENNSYLVANIA INDIAN

- Page 29 and 30: L a k e E r i e INDIANA R i v e r G

- Page 31 and 32: Olentangy River and other minor tri

- Page 33 and 34: Figure 2.6. Comparison of Late Wood

- Page 35 and 36: support the notion of resource stre

- Page 37 and 38: F4 F7 F5 F6 F3 F2 F9 F10 F12 F13 F1

- Page 39 and 40: B B M F42 F43 F41 F44 S5 S4 S1 F30

- Page 41 and 42: Table 2.3. continued Temporal Age A

- Page 43 and 44: Table 2.3. continued Temporal Age A

- Page 45 and 46: L a k e E r i e INDIANA o i O h Sal

- Page 47 and 48: Figure 2.13. Map of the Late Prehis

- Page 49 and 50: Figure 2.15. Map of households with

- Page 51 and 52: Figure 2.17. Sample of Late Prehist

- Page 53 and 54: Barkes, B. M. (1982). An Analysis o

- Page 55 and 56: Fort Ancient Tradition, edited by J

- Page 57 and 58: CHAPTER 3 “ . . . to reconstruct

- Page 59 and 60: IT TAKES A VILLAGE Figure 3.2. Arti

- Page 61 and 62: social organizations is drawn prima

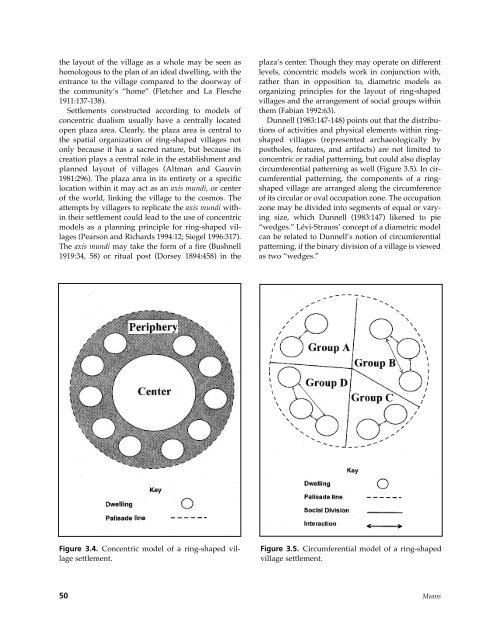

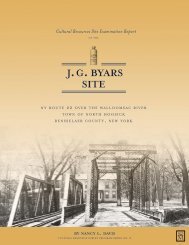

- Page 63: elements of the village, the spaces

- Page 67 and 68: egion, including Reckner (Augustine

- Page 69 and 70: Chapter 3 Modeling Village Communit

- Page 71 and 72: Figure 3.9. Architectural and nonar

- Page 73 and 74: Figure 3.11. Measuring distances in

- Page 75 and 76: Table 3.2. Descriptive Statistics f

- Page 77 and 78: DISCUSSION Table 3.3. Descriptive S

- Page 79 and 80: Figure 3.14. Box-and-whisker plot o

- Page 81 and 82: Augustine, E. A. (1938d). Important

- Page 83 and 84: Among Some Amazon Tribes. Privately

- Page 85 and 86: on Black Mesa, Arizona. The Univers

- Page 87 and 88: CHAPTER 4 THE EARLY LATE WOODLAND I

- Page 89 and 90: Figure 4.3. Gibraltar Cordmarked ce

- Page 91 and 92: Figure 4.5. Ceramics of the Gibralt

- Page 93 and 94: points and notched Chesser or Lowe

- Page 95 and 96: dated to A.D. 890 (1025) 1230 (DIC-

- Page 97 and 98: Table 4.3. Available Stable Carbon

- Page 99 and 100: where fishing and farming may have

- Page 101 and 102: Figure 4.10. Ceramic of the Sandusk

- Page 103 and 104: singular Mixter Stamped vessels typ

- Page 105 and 106: urial with the dead, broadcasted a

- Page 107 and 108: during the early Late Woodland time

- Page 109 and 110: Valley. North American Archaeologis

- Page 111 and 112: CHAPTER 5 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN TH

- Page 113 and 114: interest in exchange of service or

- Page 115 and 116:

CURRENT INVESTIGATIONS In view of t

- Page 117 and 118:

710 Area C 700 B-75084 TO-4556 TO-4

- Page 119 and 120:

Table 5.1. Summary of Artifacts fro

- Page 121 and 122:

e Bull's Point C o o t e s P a r a

- Page 123 and 124:

classification system has been appl

- Page 125 and 126:

(Crawford et al. 1997a). The same i

- Page 127 and 128:

in Ontario was Middle Woodland-deri

- Page 129 and 130:

207-212. Smithsonian Institution, W

- Page 131 and 132:

CHAPTER 6 EARLY LATE WOODLAND IN SO

- Page 133 and 134:

Figure 6.2. Lower Grand River Valle

- Page 135 and 136:

Table 6.1. Radiocarbon Dates from t

- Page 137 and 138:

segment of the terrace that effecti

- Page 139 and 140:

Figure 6.7. Meyer site terrace, vie

- Page 141 and 142:

Figure 6.10. Forster site reconstru

- Page 143 and 144:

Figure 6.12. Middle Thames River 20

- Page 145 and 146:

Figure 6.13. Site situation: a comp

- Page 147 and 148:

Dieterman, F. (2001). Princess Poin

- Page 149 and 150:

CHAPTER 7 EARLY LATE PREHISTORIC SE

- Page 151 and 152:

ticultural hamlets, small and large

- Page 153 and 154:

that Clemson Island was greatly inf

- Page 155 and 156:

local deposits. Alternately, Stimme

- Page 157 and 158:

Table 7.1. Radiocarbon Dates from S

- Page 159 and 160:

Pennsylvania continued to practice

- Page 161 and 162:

level) overlaps with the West Branc

- Page 163 and 164:

Under a population metaphysic, the

- Page 165 and 166:

Hatch, J. W., and Koontz, K. L. (19

- Page 167 and 168:

CHAPTER 8 NEW DATES FOR OWASCO POTS

- Page 169 and 170:

Table 8.1. Key Components of the Th

- Page 171 and 172:

Figure 8.1. Location of the Kipp Is

- Page 173 and 174:

Table 8.4. Carpenter Brook Phase Ho

- Page 175 and 176:

Table 8.5. Physical Characteristics

- Page 177 and 178:

Table 8.6. AMS Dates and Calibrated

- Page 179 and 180:

REFERENCES CITED Ammerman, A. J., a

- Page 181 and 182:

CHAPTER 9 PITS, PLANTS, AND PLACE:

- Page 183 and 184:

Thomas/Luckey Broome Tech N 0 0 50

- Page 185 and 186:

confluence with the Susquehanna Riv

- Page 187 and 188:

Figure 9.3. Topographic map of Broo

- Page 189 and 190:

Table 9.2. Feature Types at Thomas/

- Page 191 and 192:

Figure 9.4. Histogram of feature de

- Page 193 and 194:

Table 9.4. Plant Remains from Thoma

- Page 195 and 196:

Figure 9.7. Sample composition of n

- Page 197 and 198:

Figure 9.9. Seed composition (exclu

- Page 199 and 200:

suggests that the gathering of wild

- Page 201 and 202:

of posts may mark remnants of tempo

- Page 203 and 204:

for allowing me repeated and unteth

- Page 205 and 206:

History Press, Garden City, New Yor

- Page 207 and 208:

CHAPTER 10 UPLAND LAND USE PATTERNS

- Page 209 and 210:

LOCAL LEVEL ANALYSIS Local level an

- Page 211 and 212:

N104 E101 Unit 19A Unit 7A Unit 12A

- Page 213 and 214:

Table 10.2. Park Creek II Feature A

- Page 215 and 216:

Fea. 2 Fea. 5 0 1 2 N Figure 10.4.

- Page 217 and 218:

encounterlike hunting/butchering st

- Page 219 and 220:

END NOTES 1. A village is defined a

- Page 221 and 222:

Perrelli, D. J. (1994). Gender, Mob

- Page 223 and 224:

CHAPTER 11 EARLY LATE PREHISTORIC S

- Page 225 and 226:

Table 11.1. Upper Susquehanna Site

- Page 227 and 228:

Table 11.2. Summary of Late Middle

- Page 229 and 230:

Table 11.3. Settlement Features of

- Page 231 and 232:

approximately 1,000 sq. ft, there i

- Page 233 and 234:

Table 11.5. Summary of Seed Identif

- Page 235 and 236:

importance of hunting and hunting-r

- Page 237 and 238:

portion of the Susquehanna Valley,

- Page 239 and 240:

Herrick, J. W., and Snow, D. R. (19

- Page 241 and 242:

CHAPTER 12 WOODLAND PERIOD SETTLEME

- Page 243 and 244:

oundaries were given. According to

- Page 245 and 246:

Table 12.1: Selected Radiocarbon an

- Page 247 and 248:

shads and herrings of the family Cl

- Page 249 and 250:

consists of large concentrations of

- Page 251 and 252:

(1990) survey of recorded sites in

- Page 253 and 254:

York State 92:1-8. Busby, M. (1966)

- Page 255 and 256:

CHAPTER 13 PALEOETHNOBOTANICAL INDI

- Page 257 and 258:

Figure 13.1. Forest regions of the

- Page 259 and 260:

Table 13.1. Distribution of Nut Tre

- Page 261 and 262:

ation in feature contents. For mult

- Page 263 and 264:

Figure 13.4. Nutshell density (gray

- Page 265 and 266:

Figure 13.5. Seed density and maize

- Page 267 and 268:

Table 13.3. Seed Indicators-Maine S

- Page 269 and 270:

Table 13.4. Broome Tech Site: Selec

- Page 271 and 272:

6, and it occurred in 58 percent of

- Page 273 and 274:

Table 13.6. Continued Site Uncalibr

- Page 275 and 276:

Acknowledgments I thank John Hart f

- Page 277 and 278:

y K. J. Gremillion, pp. 161-178. Th

- Page 279 and 280:

CHAPTER 14 FROM HUNTER-GATHERER CAM

- Page 281 and 282:

Figure 14.1. Distribution of select

- Page 283 and 284:

available to Ceci were simply too l

- Page 285 and 286:

the AMS date of A.D. 1185 (A.D. 127

- Page 287 and 288:

Table 14.1. Continued Site Lab C14

- Page 289 and 290:

within single settlements remains e

- Page 291 and 292:

noncoastal residential sites certai

- Page 293 and 294:

Figure 14.3. Two stratigraphic prof

- Page 295 and 296:

to the Maritime Provinces on the Gu

- Page 297 and 298:

other related questions yet, and so

- Page 299 and 300:

Northeast Historical Archaeology 21

- Page 301 and 302:

Thomas, P. A. (1976). Contrastive s

- Page 303 and 304:

CHAPTER 15 “towns they have none

- Page 305 and 306:

Table 15.1. Key to Figure 15.1: Arc

- Page 307 and 308:

Maize will normally not preserve fo

- Page 309 and 310:

artifacts. Cowie (2000) suggests th

- Page 311 and 312:

creativity to resolve, but is also

- Page 313 and 314:

Ph.D. dissertation, Department of A

- Page 315 and 316:

CHAPTER 16 OUT OF THE BLUE AND INTO

- Page 317 and 318:

Figure 16.2. Map of the Bliss Islan

- Page 319 and 320:

shell-bearing sites located on the

- Page 321 and 322:

site. Middle Maritime Woodland occu

- Page 323 and 324:

(e.g., Black 1992:190) limit and co

- Page 325 and 326:

Table 16.3. Faunal Remains Associat

- Page 327 and 328:

and often poor vertebrate faunal pr

- Page 329 and 330:

the Maine/Maritimes area have argue

- Page 331 and 332:

SE: warm season (Rojo 1987:221); sp

- Page 333 and 334:

Ethnohistory 36:257-284. Bourque, B

- Page 335 and 336:

CHAPTER 17 ABORIGINAL LAND AND RESO

- Page 337 and 338:

Table 17.1. Chronological and Ceram

- Page 339 and 340:

Among the food plants listed above,

- Page 341 and 342:

species, the American eel (Anguilla

- Page 343 and 344:

the Early Woodland period. Tools ma

- Page 345 and 346:

Copper Resources Throughout the Lat

- Page 347 and 348:

midden deposits were located along

- Page 349 and 350:

a model with two distinct populatio

- Page 351 and 352:

Table 17.2. Summary of Landscape an

- Page 353 and 354:

File Report 93-1, Fredericton. Alle

- Page 355 and 356:

Anthropology, Temple University, Ph

- Page 357 and 358:

stone age found at Maquapit Lake. N

- Page 359 and 360:

CHAPTER 18 MAIZE AND VILLAGES: A Su

- Page 361 and 362:

use of the term “small village”

- Page 363 and 364:

1325 [1425] 1460) (Boyd et al. 1998

- Page 365 and 366:

several centuries after its first a

- Page 367 and 368:

from excavations at village sites h

- Page 369 and 370:

133-156. New York State Museum Bull

- Page 371 and 372:

longhouses. American Antiquity 55:4

- Page 373 and 374:

CONTRIBUTORS Timothy J. Abel. Carth