Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700 –1300

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

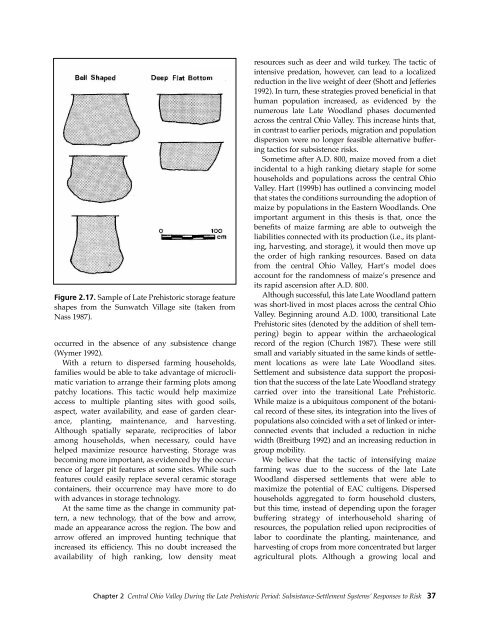

Figure 2.17. Sample of Late Prehistoric storage feature<br />

shapes from the Sunwatch Village site (taken from<br />

Nass 1987).<br />

occurred in the absence of any subsistence change<br />

(Wymer 1992).<br />

With a return to dispersed farming households,<br />

families would be able to take advantage of microclimatic<br />

variation to arrange their farming plots among<br />

patchy locations. This tactic would help maximize<br />

access to multiple planting sites with good soils,<br />

aspect, water availability, and ease of garden clearance,<br />

planting, maintenance, and harvesting.<br />

Although spatially separate, reciprocities of labor<br />

among households, when necessary, could have<br />

helped maximize resource harvesting. Storage was<br />

becoming more important, as evidenced by the occurrence<br />

of larger pit features at some sites. While such<br />

features could easily replace several ceramic storage<br />

containers, their occurrence may have more to do<br />

with advances in storage technology.<br />

At the same time as the change in community pattern,<br />

a new technology, that of the bow and arrow,<br />

made an appearance across the region. The bow and<br />

arrow offered an improved hunting technique that<br />

increased its efficiency. This no doubt increased the<br />

availability of high ranking, low density meat<br />

resources such as deer and wild turkey. The tactic of<br />

intensive predation, however, can lead to a localized<br />

reduction in the live weight of deer (Shott and Jefferies<br />

1992). In turn, these strategies proved beneficial in that<br />

human population increased, as evidenced by the<br />

numerous late Late Woodland phases documented<br />

across the central Ohio Valley. This increase hints that,<br />

in contrast to earlier periods, migration and population<br />

dispersion were no longer feasible alternative buffering<br />

tactics for subsistence risks.<br />

Sometime after A.D. 800, maize moved from a diet<br />

incidental to a high ranking dietary staple for some<br />

households and populations across the central Ohio<br />

Valley. Hart (1999b) has outlined a convincing model<br />

that states the conditions surrounding the adoption of<br />

maize by populations in the Eastern Woodlands. One<br />

important argument in this thesis is that, once the<br />

benefits of maize farming are able to outweigh the<br />

liabilities connected with its production (i.e., its planting,<br />

harvesting, and storage), it would then move up<br />

the order of high ranking resources. Based on data<br />

from the central Ohio Valley, Hart’s model does<br />

account for the randomness of maize’s presence and<br />

its rapid ascension after A.D. 800.<br />

Although successful, this late Late Woodland pattern<br />

was short-lived in most places across the central Ohio<br />

Valley. Beginning around A.D. 1000, transitional Late<br />

Prehistoric sites (denoted by the addition of shell tempering)<br />

begin to appear within the archaeological<br />

record of the region (Church 1987). These were still<br />

small and variably situated in the same kinds of settlement<br />

locations as were late Late Woodland sites.<br />

<strong>Settlement</strong> and subsistence data support the proposition<br />

that the success of the late Late Woodland strategy<br />

carried over into the transitional Late Prehistoric.<br />

While maize is a ubiquitous component of the botanical<br />

record of these sites, its integration into the lives of<br />

populations also coincided with a set of linked or interconnected<br />

events that included a reduction in niche<br />

width (Breitburg 1992) and an increasing reduction in<br />

group mobility.<br />

We believe that the tactic of intensifying maize<br />

farming was due to the success of the late Late<br />

Woodland dispersed settlements that were able to<br />

maximize the potential of EAC cultigens. Dispersed<br />

households aggregated to form household clusters,<br />

but this time, instead of depending upon the forager<br />

buffering strategy of interhousehold sharing of<br />

resources, the population relied upon reciprocities of<br />

labor to coordinate the planting, maintenance, and<br />

harvesting of crops from more concentrated but larger<br />

agricultural plots. Although a growing local and<br />

Chapter 2 Central Ohio Valley During the Late Prehistoric Period: Subsistance-<strong>Settlement</strong> Systems’ Responses to Risk 37