- Page 1:

:CN 100 =O> =00 CD CO

- Page 9 and 10:

AN INTRODUCTORY TEXT-BOOK OF LOGIC

- Page 11:

OQf I AN INTRODUCTORY TEXT-BOOK OF

- Page 14 and 15:

VI PREFACE. A text-book constructed

- Page 16 and 17:

PREFACE. logical mistakes. Some of

- Page 18 and 19:

X CONTENTS. 10. Three fundamental L

- Page 20 and 21:

Xll CONTENTS. CHAPTER VII. CONDITIO

- Page 22 and 23:

CORRECTIONS AND NOTES. PAGE LINE 21

- Page 24 and 25:

2 THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC. truths

- Page 26 and 27:

4 THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC. agreeme

- Page 28 and 29:

6 THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC. tion an

- Page 30 and 31:

; dently THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC.

- Page 32 and 33:

10 THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC. "

- Page 34 and 35:

12 THE GENERAL AIM OF LOGIC. ledge,

- Page 36 and 37:

14 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 38 and 39:

16 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 40 and 41:

1 8 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT

- Page 42 and 43:

20 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 44 and 45:

22 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 46 and 47:

24 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 48 and 49:

26 THE NAMK, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 50 and 51:

28 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 52 and 53:

3O THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 54 and 55:

32 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 56 and 57:

34 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 58 and 59:

36 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 60 and 61:

38 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 62 and 63:

40 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 64 and 65:

42 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 66 and 67:

44 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 68 and 69:

46 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 70 and 71:

48 THE NAME, THE TERM, THE CONCEPT,

- Page 72 and 73:

CHAPTER III. THE PROPOSITION, THE O

- Page 74 and 75:

52 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. we make

- Page 76 and 77:

54 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. univers

- Page 78 and 79: 56 S is not P " THE LOGICAL PR

- Page 80 and 81: 58 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. it. Aga

- Page 82 and 83: 60 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. The who

- Page 84 and 85: 62 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. earth s

- Page 86 and 87: 64 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. the ref

- Page 88 and 89: 66 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. (a] To

- Page 90 and 91: 68 THE LOGICAL PROPOSITION. (9) (a)

- Page 92 and 93: 70 OPPOSITION OF PROPOSITIONS. Logi

- Page 94 and 95: 72 " " Europeans and the

- Page 96 and 97: 74 OPPOSITION OF PROPOSITIONS. outs

- Page 98 and 99: 70 OPPOSITION OF PROPOSITIONS. incl

- Page 100 and 101: 78 of I, the falsity of E : falsity

- Page 102 and 103: 80 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. the convers

- Page 104 and 105: 82 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. the geometr

- Page 106 and 107: 84 In the second proposition, (a) m

- Page 108 and 109: 86 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. In obvertin

- Page 110 and 111: 88 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. contradicto

- Page 112 and 113: 90 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. " (3)

- Page 114 and 115: 92 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. alone, is a

- Page 116 and 117: 94 are not -fallible" ; IMMEDI

- Page 118 and 119: 96 IMMEDIATE INFERENCE. Give the ob

- Page 120 and 121: 98 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDGM

- Page 122 and 123: 100 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 124 and 125: 102 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

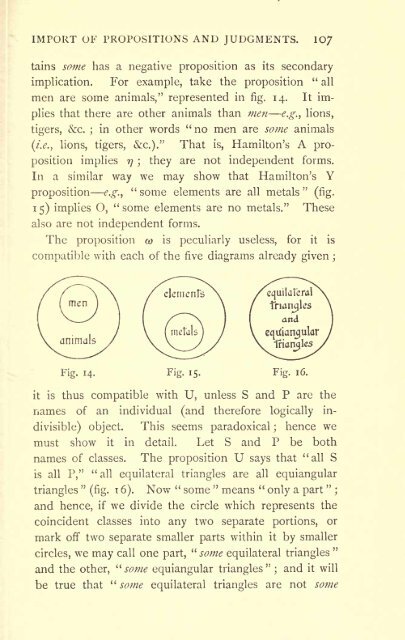

- Page 126 and 127: 104 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 130 and 131: 108 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 132 and 133: IIO IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 134 and 135: 112 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 136 and 137: 114 IMPORT OF PROPOSITIONS AND JUDG

- Page 138 and 139: Il6 MEDIATE INFERENCE merely a verb

- Page 140 and 141: Il8 MEDIATE INFERENCE The relation

- Page 142 and 143: I2O MEDIATE INFERENCE We shall firs

- Page 144 and 145: 122 MEDIATE INFERENCE The relation

- Page 146 and 147: 124 III. Relating to quality : MEDI

- Page 148 and 149: 126 MEDIATE INFERENCE hence there i

- Page 150 and 151: 128 MEDIATE INFERENCE does not forb

- Page 152 and 153: I3O MEDIATE INFERENCE II, IO, OI, a

- Page 154 and 155: 132 MEDIATE INFERENCE one premise a

- Page 156 and 157: 134 MEDIATE INFERENCE are universal

- Page 158 and 159: 136 MEDIATE INFERENCE (4) The mood

- Page 160 and 161: 138 MEDIATE INFERENCE and ask, not

- Page 162 and 163: 140 MEDIATE INFERENCE Crusoe s foot

- Page 164 and 165: 142 MEDIATE INFERENCE examples of t

- Page 166 and 167: 144 MEDIATE INFERENCE We must add t

- Page 168 and 169: 146 MEDIATE INFERENCE But in the fo

- Page 170 and 171: 148 MEDIATE INFERENCE Fig. iii. 1.

- Page 172 and 173: 150 MEDIATE INFERENCE The first s i

- Page 174 and 175: 152 MEDIATE INFERENCE The new syllo

- Page 176 and 177: 154 MEDIATE INFERENCE at ; a subjec

- Page 178 and 179:

156 MEDIATE INFERENCE expression, w

- Page 180 and 181:

158 MEDIATE INFERENCE principle, or

- Page 182 and 183:

160 MEDIATE INFERENCE a Buddhist, o

- Page 184 and 185:

162 MEDIATE INFERENCE (2) (a] Every

- Page 186 and 187:

164 MEDIATE INFERENCE. NOTE. When w

- Page 188 and 189:

1 66 THE PREDICABLES. entirely agre

- Page 190 and 191:

1 68 THE PREDICABLES. of sides defi

- Page 192 and 193:

I7O Porphyry explains the THE PREDI

- Page 194 and 195:

I?2 DEFINITION. anything, and carri

- Page 196 and 197:

1/4 become a " DEFINITION. &qu

- Page 198 and 199:

176 DEFINITION. An obviously circul

- Page 200 and 201:

1/8 DEFINITION. the formula which w

- Page 202 and 203:

ISO DEFINITION. matics, our definit

- Page 204 and 205:

l82 DEFINITION. that of "Induc

- Page 206 and 207:

1 84 DEFINITION. A scientific syste

- Page 208 and 209:

1 86 DEFINITION. classification is

- Page 210 and 211:

188 DEFINITION. goes back to Plato.

- Page 212 and 213:

IQO THE CATEGORIES OR PREDICAMENTS.

- Page 214 and 215:

192 THE CATEGORIES OR PREDICAMENTS.

- Page 216 and 217:

IQ4 THE CATEGORIES OR PREDICAMENTS.

- Page 218 and 219:

196 CHAPTER VII. CONDITIONAL ARGUME

- Page 220 and 221:

198 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND 2. Co

- Page 222 and 223:

2OO CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND for t

- Page 224 and 225:

2O2 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND The s

- Page 226 and 227:

2O4 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND "

- Page 228 and 229:

2O6 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND get f

- Page 230 and 231:

208 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND (2) S

- Page 232 and 233:

2IO CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND "

- Page 234 and 235:

212 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND The s

- Page 236 and 237:

214 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND simil

- Page 238 and 239:

2l6 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND "

- Page 240 and 241:

218 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND ticul

- Page 242 and 243:

220 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND of th

- Page 244 and 245:

222 CONDITIONAL ARGUMENTS AND NOTE

- Page 246 and 247:

224 CHAPTER VIII. THE GENERAL NATUR

- Page 248 and 249:

226 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 250 and 251:

228 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 252 and 253:

230 THE GENERAL NATURE OK INDUCTION

- Page 254 and 255:

232 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 256 and 257:

234 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 258 and 259:

236 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 260 and 261:

238 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 262 and 263:

240 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 264 and 265:

242 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 266 and 267:

244 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 268 and 269:

246 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 270 and 271:

24$ THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 272 and 273:

250 THE GENERAL NATURE OE INDUCTION

- Page 274 and 275:

252 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 276 and 277:

254 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 278 and 279:

256 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 280 and 281:

258 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 282 and 283:

260 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 284 and 285:

262 THE GENERAL NATURE OF INDUCTION

- Page 286 and 287:

264 CHAPTER IX. THE THEORY OF INDUC

- Page 288 and 289:

266 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION or peri

- Page 290 and 291:

268 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION more re

- Page 292 and 293:

2/O THE THEORY OF INDUCTION investi

- Page 294 and 295:

272 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION ment st

- Page 296 and 297:

274 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION have ev

- Page 298 and 299:

276 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION The suc

- Page 300 and 301:

278 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION We shal

- Page 302 and 303:

280 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION includi

- Page 304 and 305:

282 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION "

- Page 306 and 307:

& 284 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION "

- Page 308 and 309:

286 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION cedents

- Page 310 and 311:

288 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION of Uran

- Page 312 and 313:

2QO THE THEORY OF INDUCTION chief o

- Page 314 and 315:

2Q2 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION Thus, t

- Page 316 and 317:

294 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION 4. Veri

- Page 318 and 319:

296 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION by prov

- Page 320 and 321:

298 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION (/.*.,

- Page 322 and 323:

3OO THE THEORY OF INDUCTION has sho

- Page 324 and 325:

302 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION or comp

- Page 326 and 327:

304 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION of such

- Page 328 and 329:

306 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION examine

- Page 330 and 331:

308 THE THEORY OE INDUCTION bodies

- Page 332 and 333:

310 THE THEORY OF INDUCTION made wi

- Page 334 and 335:

312 (c) " THE THEORY OF INDUCT

- Page 336 and 337:

314 FALLACIES. (irepl <jo$i(

- Page 338 and 339:

3l6 Pyrrhus : FALLACIES. " Aio

- Page 340 and 341:

3l8 FALLACIES. De Morgan, that if i

- Page 342 and 343:

32O FALLACIES. secundum quid e.g.,

- Page 344 and 345:

322 FALLACIES. not an argument at a

- Page 346 and 347:

324 FALLACIES. conclusion are separ

- Page 348 and 349:

326 FALLACIES. what is called a Log

- Page 350 and 351:

328 FALLACIES. (c) Mai-observation

- Page 352 and 353:

330 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 354 and 355:

332 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 356 and 357:

334 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 358 and 359:

THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAISED.

- Page 360 and 361:

338 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 362 and 363:

340 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 364 and 365:

342 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 366 and 367:

344 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 368 and 369:

346 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 370 and 371:

34 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAISE

- Page 372 and 373:

350 THE PROBLEMS wnicii WE HAVE RAI

- Page 374 and 375:

352 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 376 and 377:

354 THE PROBLEMS WHICH WE HAVE RAIS

- Page 378 and 379:

NOTE. THE following mechanical devi

- Page 380 and 381:

358 Bosanquet, on Connotation of Pr

- Page 382 and 383:

360 222. (See also Immediate In fer

- Page 384:

3 62 of Disjunctive Syllogism, 205-

- Page 388 and 389:

PERIODS OF EUROPEAN LITERATURE: A C

- Page 390 and 391:

List of Books Published by ALMOND.

- Page 392 and 393:

List of Books Published by BUCHAN.

- Page 394 and 395:

List of Books Published by CHRISTIS

- Page 396 and 397:

io List of Books Published by DRUMM

- Page 398 and 399:

12 List of Books Published by FORD.

- Page 400 and 401:

14 List of Books Published by GRAY.

- Page 402 and 403:

1 6 List of Books Published by HENS

- Page 404 and 405:

1 8 List of Books Published by LANG

- Page 406 and 407:

20 List of Books Published by MAIR.

- Page 408 and 409:

22 List of Books Published by MODER

- Page 410 and 411:

24 List of Books Published by NICHO

- Page 412 and 413:

26 List of Books Published by PKEST

- Page 414 and 415:

28 List of Books Published by SETH

- Page 416 and 417:

30 List of Books Published by STEWA

- Page 418:

32 Books Published by William Black