Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

118<br />

Security of tenure<br />

Fully legal<br />

Degree of legality<br />

Zero legality<br />

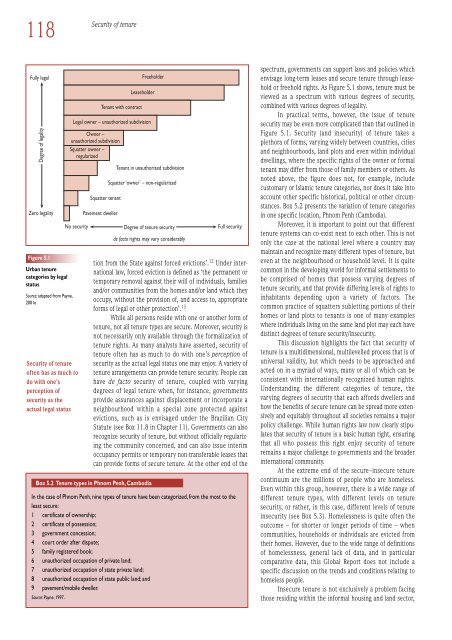

Figure 5.1<br />

Urban tenure<br />

categories by legal<br />

status<br />

Source: adapted from Payne,<br />

2001e<br />

No security<br />

Security of tenure<br />

often has as much to<br />

do with <strong>on</strong>e’s<br />

percepti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

security as the<br />

actual legal status<br />

Squatter tenant<br />

Pavement dweller<br />

Tenant with c<strong>on</strong>tract<br />

Freeholder<br />

Leaseholder<br />

Legal owner – unauthorized subdivisi<strong>on</strong><br />

Owner –<br />

unauthorized subdivisi<strong>on</strong><br />

Squatter owner –<br />

regularized<br />

Tenant in unauthorized subdivisi<strong>on</strong><br />

Squatter ‘owner’ – n<strong>on</strong>-regularized<br />

Degree of tenure security<br />

de facto rights may vary c<strong>on</strong>siderably<br />

Full security<br />

ti<strong>on</strong> from the State against forced evicti<strong>on</strong>s’. 12 Under internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

law, forced evicti<strong>on</strong> is defined as ‘the permanent or<br />

temporary removal against their will of individuals, families<br />

and/or communities from the homes and/or land which they<br />

occupy, without the provisi<strong>on</strong> of, and access to, appropriate<br />

forms of legal or other protecti<strong>on</strong>’. 13<br />

While all pers<strong>on</strong>s reside with <strong>on</strong>e or another form of<br />

tenure, not all tenure types are secure. Moreover, security is<br />

not necessarily <strong>on</strong>ly available through the formalizati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

tenure rights. As many analysts have asserted, security of<br />

tenure often has as much to do with <strong>on</strong>e’s percepti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

security as the actual legal status <strong>on</strong>e may enjoy. A variety of<br />

tenure arrangements can provide tenure security. People can<br />

have de facto security of tenure, coupled with varying<br />

degrees of legal tenure when, for instance, governments<br />

provide assurances against displacement or incorporate a<br />

neighbourhood within a special z<strong>on</strong>e protected against<br />

evicti<strong>on</strong>s, such as is envisaged under the Brazilian City<br />

Statute (see Box 11.8 in Chapter 11). Governments can also<br />

recognize security of tenure, but without officially regularizing<br />

the community c<strong>on</strong>cerned, and can also issue interim<br />

occupancy permits or temporary n<strong>on</strong>-transferable leases that<br />

can provide forms of secure tenure. At the other end of the<br />

Box 5.2 Tenure types in Phnom Penh, Cambodia<br />

In the case of Phnom Penh, nine types of tenure have been categorized, from the most to the<br />

least secure:<br />

1 certificate of ownership;<br />

2 certificate of possessi<strong>on</strong>;<br />

3 government c<strong>on</strong>cessi<strong>on</strong>;<br />

4 court order after dispute;<br />

5 family registered book;<br />

6 unauthorized occupati<strong>on</strong> of private land;<br />

7 unauthorized occupati<strong>on</strong> of state private land;<br />

8 unauthorized occupati<strong>on</strong> of state public land; and<br />

9 pavement/mobile dweller.<br />

Source: Payne, 1997.<br />

spectrum, governments can support laws and policies which<br />

envisage l<strong>on</strong>g-term leases and secure tenure through leasehold<br />

or freehold rights. As Figure 5.1 shows, tenure must be<br />

viewed as a spectrum with various degrees of security,<br />

combined with various degrees of legality.<br />

In practical terms, however, the issue of tenure<br />

security may be even more complicated than that outlined in<br />

Figure 5.1. Security (and insecurity) of tenure takes a<br />

plethora of forms, varying widely between countries, cities<br />

and neighbourhoods, land plots and even within individual<br />

dwellings, where the specific rights of the owner or formal<br />

tenant may differ from those of family members or others. As<br />

noted above, the figure does not, for example, include<br />

customary or Islamic tenure categories, nor does it take into<br />

account other specific historical, political or other circumstances.<br />

Box 5.2 presents the variati<strong>on</strong> of tenure categories<br />

in <strong>on</strong>e specific locati<strong>on</strong>, Phnom Penh (Cambodia).<br />

Moreover, it is important to point out that different<br />

tenure systems can co-exist next to each other. This is not<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly the case at the nati<strong>on</strong>al level where a country may<br />

maintain and recognize many different types of tenure, but<br />

even at the neighbourhood or household level. It is quite<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> in the developing world for informal settlements to<br />

be comprised of homes that possess varying degrees of<br />

tenure security, and that provide differing levels of rights to<br />

inhabitants depending up<strong>on</strong> a variety of factors. The<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> practice of squatters subletting porti<strong>on</strong>s of their<br />

homes or land plots to tenants is <strong>on</strong>e of many examples<br />

where individuals living <strong>on</strong> the same land plot may each have<br />

distinct degrees of tenure security/insecurity.<br />

This discussi<strong>on</strong> highlights the fact that security of<br />

tenure is a multidimensi<strong>on</strong>al, multilevelled process that is of<br />

universal validity, but which needs to be approached and<br />

acted <strong>on</strong> in a myriad of ways, many or all of which can be<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sistent with internati<strong>on</strong>ally recognized human rights.<br />

Understanding the different categories of tenure, the<br />

varying degrees of security that each affords dwellers and<br />

how the benefits of secure tenure can be spread more extensively<br />

and equitably throughout all societies remains a major<br />

policy challenge. While human rights law now clearly stipulates<br />

that security of tenure is a basic human right, ensuring<br />

that all who possess this right enjoy security of tenure<br />

remains a major challenge to governments and the broader<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>al community.<br />

At the extreme end of the secure–insecure tenure<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tinuum are the milli<strong>on</strong>s of people who are homeless.<br />

Even within this group, however, there is a wide range of<br />

different tenure types, with different levels <strong>on</strong> tenure<br />

security, or rather, in this case, different levels of tenure<br />

insecurity (see Box 5.3). Homelessness is quite often the<br />

outcome – for shorter or l<strong>on</strong>ger periods of time – when<br />

communities, households or individuals are evicted from<br />

their homes. However, due to the wide range of definiti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of homelessness, general lack of data, and in particular<br />

comparative data, this <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> does not include a<br />

specific discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the trends and c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s relating to<br />

homeless people.<br />

Insecure tenure is not exclusively a problem facing<br />

those residing within the informal housing and land sector,