Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

182<br />

Natural and human-made disasters<br />

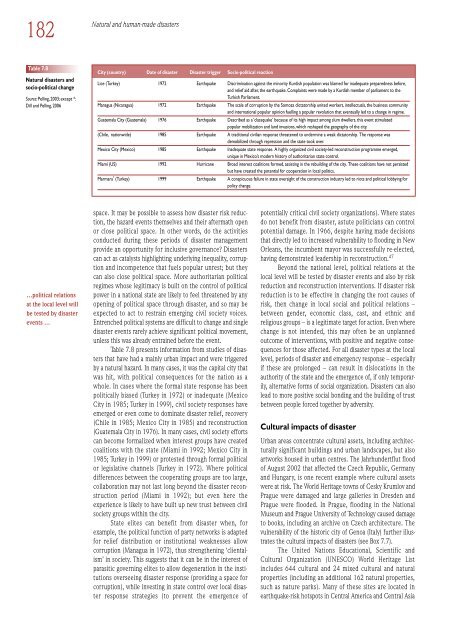

Table 7.8<br />

Natural disasters and<br />

socio-political change<br />

Source: Pelling, 2003; except *:<br />

Dill and Pelling, 2006<br />

City (country) Date of disaster Disaster trigger Socio-political reacti<strong>on</strong><br />

Lice (Turkey) 1972 Earthquake Discriminati<strong>on</strong> against the minority Kurdish populati<strong>on</strong> was blamed for inadequate preparedness before,<br />

and relief aid after, the earthquake. Complaints were made by a Kurdish member of parliament to the<br />

Turkish Parliament.<br />

Managua (Nicaragua) 1972 Earthquake The scale of corrupti<strong>on</strong> by the Somoza dictatorship united workers, intellectuals, the business community<br />

and internati<strong>on</strong>al popular opini<strong>on</strong> fuelling a popular revoluti<strong>on</strong> that eventually led to a change in regime.<br />

Guatemala City (Guatemala) 1976 Earthquake Described as a ‘classquake’ because of its high impact am<strong>on</strong>g slum dwellers, this event stimulated<br />

popular mobilizati<strong>on</strong> and land invasi<strong>on</strong>s, which reshaped the geography of the city.<br />

(Chile, nati<strong>on</strong>wide) 1985 Earthquake A traditi<strong>on</strong>al civilian resp<strong>on</strong>se threatened to undermine a weak dictatorship. The resp<strong>on</strong>se was<br />

demobilized through repressi<strong>on</strong> and the state took over.<br />

Mexico City (Mexico) 1985 Earthquake Inadequate state resp<strong>on</strong>se. A highly organized civil society-led rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> programme emerged,<br />

unique in Mexico’s modern history of authoritarian state c<strong>on</strong>trol.<br />

Miami (US) 1992 Hurricane Broad interest coaliti<strong>on</strong>s formed, assisting in the rebuilding of the city. These coaliti<strong>on</strong>s have not persisted<br />

but have created the potential for cooperati<strong>on</strong> in local politics.<br />

Marmara * (Turkey) 1999 Earthquake A c<strong>on</strong>spicuous failure in state oversight of the c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> industry led to riots and political lobbying for<br />

policy change.<br />

…political relati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

at the local level will<br />

be tested by disaster<br />

events …<br />

space. It may be possible to assess how disaster risk reducti<strong>on</strong>,<br />

the hazard events themselves and their aftermath open<br />

or close political space. In other words, do the activities<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted during these periods of disaster management<br />

provide an opportunity for inclusive governance? Disasters<br />

can act as catalysts highlighting underlying inequality, corrupti<strong>on</strong><br />

and incompetence that fuels popular unrest; but they<br />

can also close political space. More authoritarian political<br />

regimes whose legitimacy is built <strong>on</strong> the c<strong>on</strong>trol of political<br />

power in a nati<strong>on</strong>al state are likely to feel threatened by any<br />

opening of political space through disaster, and so may be<br />

expected to act to restrain emerging civil society voices.<br />

Entrenched political systems are difficult to change and single<br />

disaster events rarely achieve significant political movement,<br />

unless this was already entrained before the event.<br />

Table 7.8 presents informati<strong>on</strong> from studies of disasters<br />

that have had a mainly urban impact and were triggered<br />

by a natural hazard. In many cases, it was the capital city that<br />

was hit, with political c<strong>on</strong>sequences for the nati<strong>on</strong> as a<br />

whole. In cases where the formal state resp<strong>on</strong>se has been<br />

politically biased (Turkey in 1972) or inadequate (Mexico<br />

City in 1985; Turkey in 1999), civil society resp<strong>on</strong>ses have<br />

emerged or even come to dominate disaster relief, recovery<br />

(Chile in 1985; Mexico City in 1985) and rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong><br />

(Guatemala City in 1976). In many cases, civil society efforts<br />

can become formalized when interest groups have created<br />

coaliti<strong>on</strong>s with the state (Miami in 1992; Mexico City in<br />

1985; Turkey in 1999) or protested through formal political<br />

or legislative channels (Turkey in 1972). Where political<br />

differences between the cooperating groups are too large,<br />

collaborati<strong>on</strong> may not last l<strong>on</strong>g bey<strong>on</strong>d the disaster rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong><br />

period (Miami in 1992); but even here the<br />

experience is likely to have built up new trust between civil<br />

society groups within the city.<br />

State elites can benefit from disaster when, for<br />

example, the political functi<strong>on</strong> of party networks is adapted<br />

for relief distributi<strong>on</strong> or instituti<strong>on</strong>al weaknesses allow<br />

corrupti<strong>on</strong> (Managua in 1972), thus strengthening ‘clientalism’<br />

in society. This suggests that it can be in the interest of<br />

parasitic governing elites to allow degenerati<strong>on</strong> in the instituti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

overseeing disaster resp<strong>on</strong>se (providing a space for<br />

corrupti<strong>on</strong>), while investing in state c<strong>on</strong>trol over local disaster<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>se strategies (to prevent the emergence of<br />

potentially critical civil society organizati<strong>on</strong>s). Where states<br />

do not benefit from disaster, astute politicians can c<strong>on</strong>trol<br />

potential damage. In 1966, despite having made decisi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

that directly led to increased vulnerability to flooding in New<br />

Orleans, the incumbent mayor was successfully re-elected,<br />

having dem<strong>on</strong>strated leadership in rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>. 47<br />

Bey<strong>on</strong>d the nati<strong>on</strong>al level, political relati<strong>on</strong>s at the<br />

local level will be tested by disaster events and also by risk<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> and rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> interventi<strong>on</strong>s. If disaster risk<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> is to be effective in changing the root causes of<br />

risk, then change in local social and political relati<strong>on</strong>s –<br />

between gender, ec<strong>on</strong>omic class, cast, and ethnic and<br />

religious groups – is a legitimate target for acti<strong>on</strong>. Even where<br />

change is not intended, this may often be an unplanned<br />

outcome of interventi<strong>on</strong>s, with positive and negative c<strong>on</strong>sequences<br />

for those affected. For all disaster types at the local<br />

level, periods of disaster and emergency resp<strong>on</strong>se – especially<br />

if these are prol<strong>on</strong>ged – can result in dislocati<strong>on</strong>s in the<br />

authority of the state and the emergence of, if <strong>on</strong>ly temporarily,<br />

alternative forms of social organizati<strong>on</strong>. Disasters can also<br />

lead to more positive social b<strong>on</strong>ding and the building of trust<br />

between people forced together by adversity.<br />

Cultural impacts of disaster<br />

Urban areas c<strong>on</strong>centrate cultural assets, including architecturally<br />

significant buildings and urban landscapes, but also<br />

artworks housed in urban centres. The Jahrhundertflut flood<br />

of August 2002 that affected the Czech Republic, Germany<br />

and Hungary, is <strong>on</strong>e recent example where cultural assets<br />

were at risk. The World Heritage towns of Cesky Krumlov and<br />

Prague were damaged and large galleries in Dresden and<br />

Prague were flooded. In Prague, flooding in the Nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Museum and Prague University of Technology caused damage<br />

to books, including an archive <strong>on</strong> Czech architecture. The<br />

vulnerability of the historic city of Genoa (Italy) further illustrates<br />

the cultural impacts of disasters (see Box 7.7).<br />

The United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Educati<strong>on</strong>al, Scientific and<br />

Cultural Organizati<strong>on</strong> (UNESCO) World Heritage List<br />

includes 644 cultural and 24 mixed cultural and natural<br />

properties (including an additi<strong>on</strong>al 162 natural properties,<br />

such as nature parks). Many of these sites are located in<br />

earthquake-risk hotspots in Central America and Central Asia